Dark Mofo 2018 Waterfront Crosses. Photo Credit: Mona/Dark Mofo/Rémi Chauvin. Image Courtesy Dark Mofo, Hobart, Tasmania, Australia.

Erecting its inverted crosses between Hobart’s local heritage buildings, Mona has invited into Tasmania the greatest level of artistic controversy the state has ever enjoyed.

Beyond the museum itself – complete with its wall of vagina sculptures and the room entirely dedicated to a ‘shit machine‘ – the gigantic gallery of old and new art has undoubtedly penetrated the very heart of our city.

It paints the town red, quite literally, throughout the deepest nights of winter. It gathers onlookers who scurry in excitement to watch a man buried alive in the name of art. It evokes fear in Christian lobbyists who exclaim that ‘we’re dealing with real spiritual forces here’ – let’s not invite them in!

From the perspective of an average Hobartian, it’s admittedly amusing to step back and witness the disruption of our state’s dubious reputation, from a land of ‘dregs, bogans and third-generation morons‘ through to ‘Australia’s best tourism destination‘.

But when we consider daily life on the island, it’s also fascinating to be trapped inside ‘the Mona effect’ – a phrase uttered in many a casual conversation between those of us interested not only in arts and culture; but in tourism, business, and hospitality, too.

Nevertheless, there’s been somewhat of a black hole when it comes to dialogue surrounding the very real impact Mona has made on what’s arguably now perceived as the underdog of Tasmanian fine art: the local independent gallery scene. After all, how can a small gallery compete with an institution as impossibly large as Mona?

Bett Gallery director Emma Bett experienced a dip in engagement with her family’s long-standing gallery space when Mona started to become ‘the destination’ for tourists to visit.

‘If they flew in for a day or so, it would be Mona they would go to – not us anymore,’ Bett said.

It was a ‘detrimental effect’, albeit one with a very shallow echo of the sentiments of former Lord Mayor Ron Christie (this week outvoted), who worried about the damage Mona was causing to our community.

Shallow, that is, because Bett also says it didn’t take long for things to come ‘full circle’.

The Bett Gallery recently moved from the popular restaurant strip of North Hobart to the heart of Hobart’s CBD (not a minute’s walk from Mona’s own Odeon Theatre). And these days, her local gallery is booming.

‘Our clients are coming to visit us a lot more often,’ Bett explains. ‘We used to have to make a real effort to go interstate or even overseas to touch base with clients.’

It’s a reflection of the island’s burgeoning reputation as a hot-spot for art industry professionals and curators who might visit for Mona, but also like to ‘stick their heads in’ to galleries like the Bett while they’re here.

‘At any given moment, someone from The New York Times will just walk through the door – so you have to be prepared for that, which we never had to previously,’ Bett enthuses. ‘On that level, it’s really stepped up.’

Room for everyone?

While the Bett Gallery is considered one of the capital city’s most prestigious commercial galleries, not all independent spaces consider themselves lucky enough to receive the same high level of media interest and publicity. And for these others, it can be tough work to get the word out in a suffering commercial media landscape that’s saturating local readers with clickbait about Hobart’s comical reactions to Mona’s controversial installations.

For Penny Contemporary director Sonia Penny, it comes down to the very fact that ‘Mona has the brand behind it’.

‘Mona just mentions something, and people are there,’ Penny says.

Much of Penny’s time is spent posting out flyers and booking advertising space in publications. Of the 40 artists her gallery represents, about half are Tasmanian – the other half are interstate and international talent.

Contrary to the widespread local media coverage of Mona’s international festival and exhibition artists, Penny says she’s found ‘you’re much more supported by the media or the Hobart arts community if you are exhibiting Tasmanian artists’.

But, interestingly, she also states: ‘I don’t see that Mona takes anything away from us at all.’

A consistency among these local gallerists is the view that our small creative community operates as an ecosystem in which Mona is just one part – but not the dominating part.

Those who live in Tasmania might relate to the sentiment that there’s room for everyone.

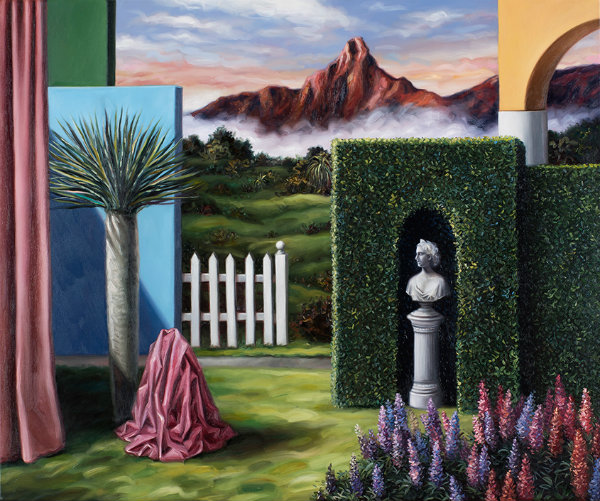

Amber Koroluk-Stephenson, Anne and Aphrodite (2018), oil on linen, 84 x 101cm. Image courtesy the artist.

The Penny Contemporary gallery’s point-of-difference comes through Penny’s selection of lower-cost, higher-stylistic-risk art that she says doesn’t appeal to an ‘elite group of buyers’.

‘We are very contemporary – a lot of people don’t like the art that we have on the walls because it’s not pretty roses on a wall,’ she says. ‘But I see our gallery as complementing all the other galleries, and vice versa.’

It’s a view surely shared by Nolan Art’s Betty Nolan, who offers art education through her gallery in a multi-purpose set-up that appears to be the only one of its kind in Hobart.

In the heights of the Salamanca Arts Centre – a hub consisting of the Long Gallery, Sidespace Gallery, Top Gallery, Peacock Theatre, and Founders Room among others creative spaces – Nolan’s own gallery hosts public exhibitions of artworks as well as art classes in an equally large space.

Nolan, a fine artist herself, has shaped her gallery strategically. She has felt a decreasing market for artworks in general, during an era in which ‘there’s this idea that we’re saturated with things’.

‘There is more of a resistance to buying things regularly,’ she says.

‘So, with the people downsizing – which is certainly a Baby Boomer thing – that means smaller homes and fewer walls and so on. With that also comes a desire to buy experiences.’

And that’s meant a boom in the gallery’s sales of art education – but also follows a local trend that sees companies from all industries jump on the bandwagon of Mona’s large-scale events in the cultural calendar.

Just as shopfronts shine red lights into their windows to join in a ritualistic tradition of Dark Mofo, Nolan Art joins into the widespread community spirit that emerges during the Mona seasons.

‘It’s a time to say something important. So this year was a show only by women, mainly young women and curated by young female artists,’ Nolan says of her contribution to the winter festival period.

‘It’s not promoted through Mona, but I try to have something that’s a more difficult show than I would have at other times of year.’

It shines a light on the dualities of the Tasmanian audience: the progressive demographic of Mona, and the seemingly undisturbed locals who form ‘a completely different group of people’.

‘The ordinary Tasmanian audience is, in my opinion, quite conventional,’ Nolan says.

‘What they like is very much determined by the mainstream galleries. So the belief that ‘an artwork’ is a painting on canvas, preferably an oil painting, is out there. And that means a fairly conservative market here.’

AN INVADED LANDSCAPE

Leading Hobart painter Amber Koroluk-Stephenson’s practice is arguably centred around the fractured idea of the ‘ordinary Tasmanian’. In her works can be seen a utopic suburban landscape, picture-perfect families frolicking on manicured lawns; but often juxtaposed by a subtle object or element of nature that seems out of place. As if something has invaded the landscape.

Much like Mona.

‘As an expanded brand or institution, it cannot be denied that Mona has had a significant transformative effect on the social, cultural, and economic landscape in Hobart,’ Koroluk-Stephenson said.

‘A large number of local hospitality and tourism businesses seem to be thriving relative to the pre-Mona era, and real estate prices have risen a staggering amount, [so much so] that I have been left wondering how many low-income locals will ever get their slice of the Australian dream.’

Read: Hobart’s poorer suburbs are missing out on the ‘MONA effect’

It’s a concern of Mona founder David Walsh himself, who has long spoken about keeping Mona accessible to the local community, forgoing entry fees for locals and creating hundreds of full-time jobs through the construction of his sites and events.

Koroluk-Stephenson herself was a Mona employee just a few years ago, working as a gallery attendant while completing her Bachelor of Fine Arts with the University of Tasmania.

‘When the museum opened, the mood was an overwhelming and intoxicating frenzy,’ she recalls.

‘I would say my time there broadened my art vocabulary, and has enabled me to gain some insights into ways different artist and curators communicate their ideas and interpret the world.’

Mona curator Jarrod Rawlins’ own background is as co-founder and director of Melbourne’s Uplands Gallery, which has certainly made its mark in his current role at the Tasmanian museum space.

‘Obviously, my experience as a gallerist before moving to Hobart gives me a good understanding of what role a gallery plays in the relationship between an artist and a curator, and I have a lot of respect for that relationship,’ Rawlins said.

In his consideration of Hobart’s surrounding galleries and artistic community, he rejects the idea that Mona has any negative impact on the creative industries – consistent, of course, with the industry’s own voices.

‘I haven’t experienced anything directly that I would classify as competition or rivalry; quite the opposite, really: all very helpful and generous at every interaction,’ he says.

‘And as I try and keep my head down and away from negative conversations, if it does exist, anyone who knows me knows not to bring it up.’

Even when they do, members of Tasmania’s cultural community are certainly there to look out for each other. As Bett says of the trolls: ‘I think you’re always going to get that, especially in a small town.

‘You’re always going to get your whingers. Let them do it.’