The term ‘placemaking’ has been fashionably adopted in recent years to describe the ‘uniqueness’ of a place, often navigated through cultural engagement, tropes around ‘liveability’ and hooks driving destination tourism.

At the centre of this conversation is a boom in new galleries and museums – a boom that is in sync with a rise in First Nations arts jobs, which ArtsHub reported earlier this year.

But there is a further shift at play here.

Heralding these new cultural venues is an emerging trend in commissioning First Nations artists to create bold signature artworks that speak to Country and community – placing them as a more permanent Welcome to Country for these venues – and foregrounding the audience experience.

‘Placemaking is a buzz term,’ said Susie Anderson (Wurundjeri).

‘It is an interesting concept that a digital media architecture [commission] could be this element of placemaking, because digital by its nature is transient.’ Anderson is talking about Digital Birthing Tree – 226 phone-sized, touch-enabled screens located behind polished Venetian glass bricks, rendering the façade of the yet to be opened Science Gallery Melbourne as an ever changing canvas for digital storytelling and interactive media.

Co-creator of the work, and Digital Content Producer for the new museum, Anderson believes that we are getting better at acknowledging the country these buildings sit upon through commissions.

Read: Place names: Reinstating Indigenous knowledge in the public domain

‘There is this a more prolific understanding of foregrounding First Nations stories, and the welcome into a space – it is quiet mainstream now.

‘Obviously we want a complex, embedded acknowledgment and relationships in our cultural institutions, but I definitely think that there has been a shift, and putting that conversation up front is welcomed,’ Anderson told ArtsHub.

It was a view shared by artist Tony Albert (Girramay, Yidinji and Kuku-Yalanji ), who’s work A House of Discards (2019) was recently unveiled ahead of the opening of Shepparton Art Museum (SAM) in regional Victoria.

Albert told ArtsHub: ‘When we consider these sculptures, the actual visit starts before you even enter the building. And when we honour the significance of that site – that place – that changes the whole vernacular of what art is, what the Indigenous experience can be.’

He implied that it puts visitors in the right ‘head space’ to then consider what is inside these buildings, adding that it brings our ‘general psyche a step closer to our attachment to the land we are on.’

Albert said that he didn’t consider the placement of commissions by Aboriginal artists outside galleries as ‘trending’ but more a case of deep understanding lead by the arts.

‘It is not tokenistic or P.C. – it is just part of life,’ Albert added. ‘Today we have Welcome to Country in banks! 20 years ago it was in the gallery – the arts have really been leaders in many ways.’

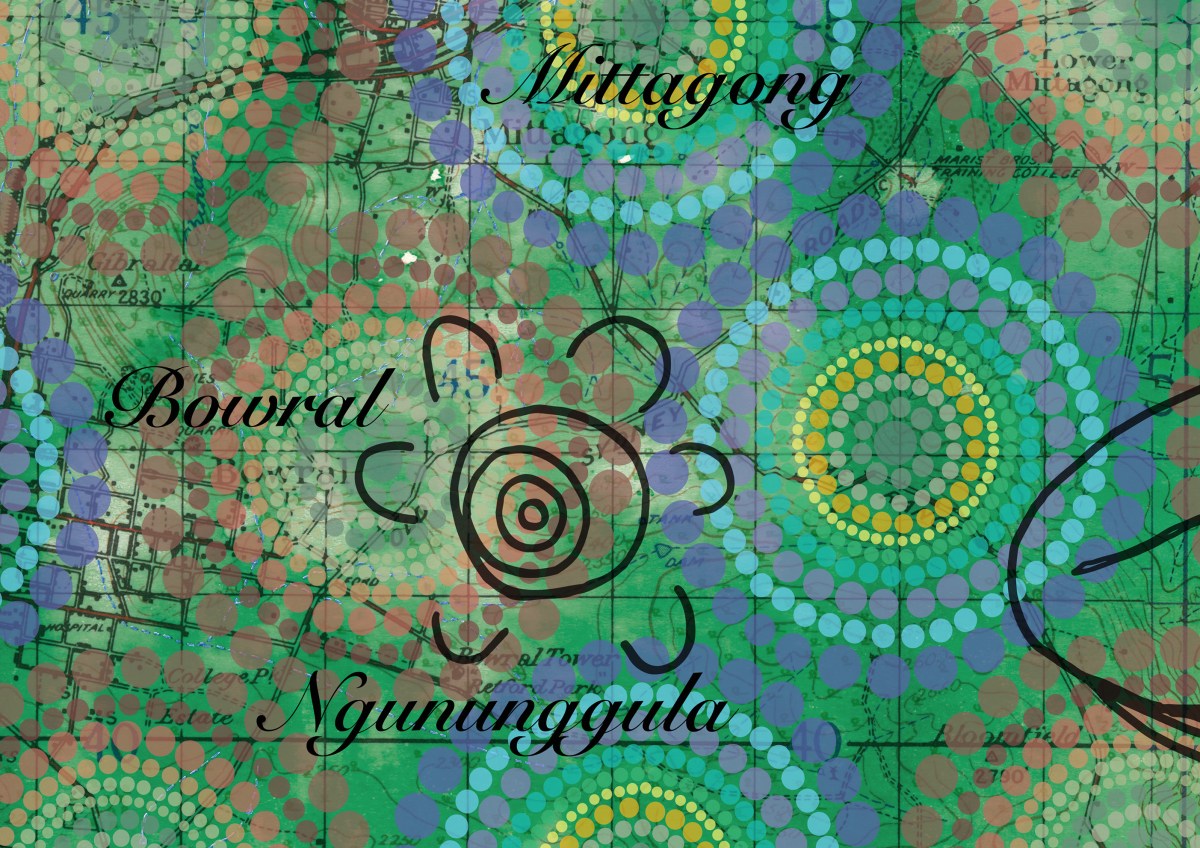

Artist Megan Cope (Quandamooka) will unveil a new welcome work she has created with community for Ngnunggula, NSW’s latest regional gallery to open in Bowral in the coming weeks.

Cope told ArtsHub: ‘It is divided in the community, [they are] not sure whether these institutions are genuine about this process or formality, or whether it is just tokenistic. Even the process of acknowledging County has been formalised, and is normalising what was radical ten years ago, and that is really positive.’

Cope said it was a priority for the vision of the Ngnunggula, which has also been signalled in the dual naming of the gallery.

‘It is changing the paradigm and the frameworks in which curators and directors are generating culture in their institutions, and more so in the regional galleries,’ she said.

FIRST ENGAGEMENT IS FIRST NATION LED

Megan Cope has created a large-scale mapping piece, made in collaboration with local Gundungurra Elder Aunty Velma Mulcahy OAM and the broader Southern Highlands Aboriginal community.

It will be the first Entry Pavilion Commission, an annual initiative which speaks to the Gallery’s commitment to celebrating Gundungurra language and culture by inviting an Aboriginal artist or collectives to work with the community to create a site-specific installation in Ngununggula’s Entry Pavilion.

Cope explained: ‘I take this work very seriously, when it comes to First Nations recognition of land, history and culture. The gallery was up for following the protocols and doing things right, in terms of engaging with the community. It seems to me to be a really genuine commitment.’

‘There is a perception that if I am Aboriginal I can say anything I want about Aboriginal [subjects] in Australia – that is a real flattened colonial way of seeing things,’ said Cope. ‘But just like any other visitor to that Country, I pay respect to the Elders and asked Aunty Val what she would like to see in the space, and if she could advise on that, and how I could – as an artist – visually represent that, and create a sense of pride and ownership of Gundungurra Country.’

Cope added that in her research for the project she discovered that 22 Aboriginal families live in the region, largely ignored to date.

‘Areas where that history is rendered out of the landscape, it is very important for cultural places like regional galleries, and the Council, to highlight and include the diversity and the community, and our responsibility to look after the country and care for it – not just for Aboriginal people but for everyone who lives there,’ said Cope.

In many ways, Cope has been a kind of quasi-director, choreographing the material created by community to tell their story. A collection of drawings of animals, plants, rivers and significant places are overlaid on a military map, as the base representation of country.’

Storytelling is also at the heart of the Science Museum Melbourne’s façade commission. The Digital Birthing Tree, draws on the University’s vast archives and collections material to uncover untold stories about the site, the Royal Women’s Hospital.

‘We wanted to acknowledge it was a hard place for many women; the first Aboriginal nurse, many refugee women, and Aboriginal women who had their babies taken from them. So the resulting piece includes a smoking ceremony as part of the sequence. It was to offer this idea of a cleansing moment before entering the building; to think about how you can reset the stories therein,’ Anderson explained.

This came through in the research for this commission. ‘We talked to lots of people – Waradju Elders, Uni stakeholders, my network, young contemporary Indigenous writers and researchers – I like the idea of an offering with those different perspectives; to take what you need and leave what you don’t.’

She agreed with Cope that we are starting to move beyond the point that whenever ‘anything Aboriginal comes up, they turn to the [blak] person in the room to speak on this … [Rather] everyone is respected for what they do, and not just their identity.’

‘The whole organisation is interested in peeling back the layers of science – and core to that is this first engagement that asks, how can we do that better and how to repair those relationships. It is about decolonising the topography,’ Anderson told ArtsHub.

She added: ‘The Science gallery has really invested in forwarding First Nations voices, by letting Aboriginal people be experts in their field, and not just using their inherent knowledge as story tellers; that is respectful.’

INSIDE / OUTSIDE: A HOLISTIC NARRATIVE

While Tony Albert’s sculpture welcomes visitors to SAM, in contrast, it was not commissioned for the site. It was however a very deliberate acquisition for the gallery’s forecourt, connecting with Albert’s works held in the SAM Collection.

SAM had purchased a suite of works from Albert’s Brothers series, which was pivotal changing point for them.

‘Their communities coming in, and seeing themselves represented in the gallery space was hugely important – and popular – so when the potential came up for an outdoor work with the new gallery, it made sense to consider a work like this,’ said Albert.

House of Discards expands upon Albert’s ongoing use of “Aboriginalia” style playing cards to reflect on the legacy of colonisation and cultural misrepresentation in this country. Reaching nearly five metres, the towering steel structure resembles a supersized house of playing cards.

‘Reduced to black and white plains placed back-to-back, the work puts into stark contrast Indigenous and non-Indigenous perspectives on a national history founded in the dispossession of First Nations Peoples, while also alluding to the conjoined nature of our future,’ explained the gallery.

‘The structure (and the history it speaks of) appears precarious, yet its inflated rendering in steel also suggests the possibility of constructing something sturdier if all elements can work together,’ the statement added.

Albert speaks also of siting the work on country as a conversation starter to our care for country, from an environmental perspective.

It was a view shared by Anderson: ‘I guess that speaks to – if you think about the minimal intervention and sustainable practice of Aboriginal people on the land for so long – the enduring things is the story not the object so if we can transfer that idea onto what we do as digital story tellers – there’s some solace in that,’ she added of the digital project.

Read: New Australian Galleries and Museums opening in 2021

Also reshaping priorities and vision, HOTA Gallery opened on the Gold Coast earlier this year, with two signature commissioned artworks – one at each entrance to the gallery. One was by Sri-Lankan born, Sydney based artist Ramesh Mario Nithiyendran, and the other by Waanyi artist Judy Watson.

Watson was also charged with creating a new work to make the tenth anniversary of Brisbane’s Gallery of Modern Art (GOMA) in 2016. She created a bronze sculpture titled tow row, inspired by the woven fishing nets used by Aboriginal communities who fished the banks of Brisbane River and Maiwar Green, adjoining the site.

In an earlier ArtsHub interview, Watson welcomed the commission as a fitting way for visitors to begin their gallery visit. ‘I think it is really important that there is an Indigenous presence to the viewer as they come to GOMA and the cultural precinct – it is an important recognition.’

This week QAGOMA has launched an immersive digital experience that animates and illuminates the significance of tow row, accessed onsite via a QR code or online.

QLD Minister for the Arts Leeanne Enoch said of the initiative: ‘The addition of this dynamic digital reality experience will help unlock deeper meaning about the sculpture, as well as the rich history and culture surrounding the creation and use of these fishing nets by First Nations people.

‘I commend QAGOMA for launching this initiative during the Year of Indigenous Tourism to give visitors a unique insight into the story of the sculpture and our shared heritage,’ Enoch added.

Ngnunggula is scheduled to open 25 September.

Shepparton Art Museum is scheduled to open 15 October.

After repeated cancelled openings due to lockdowns, Science Gallery Melbourne is ready and waiting to throw open its doors when lockdowns are lifted.

Visitors can access the Judy Watson’s digital activation of her sculpture onsite at GOMA via a QR code or online.