Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are advised this article contains images of deceased people.

Historical research of the last 20 years has confirmed the central importance of the killing times. They lasted far longer and were much more deadly than generations of Australians were led to believe.

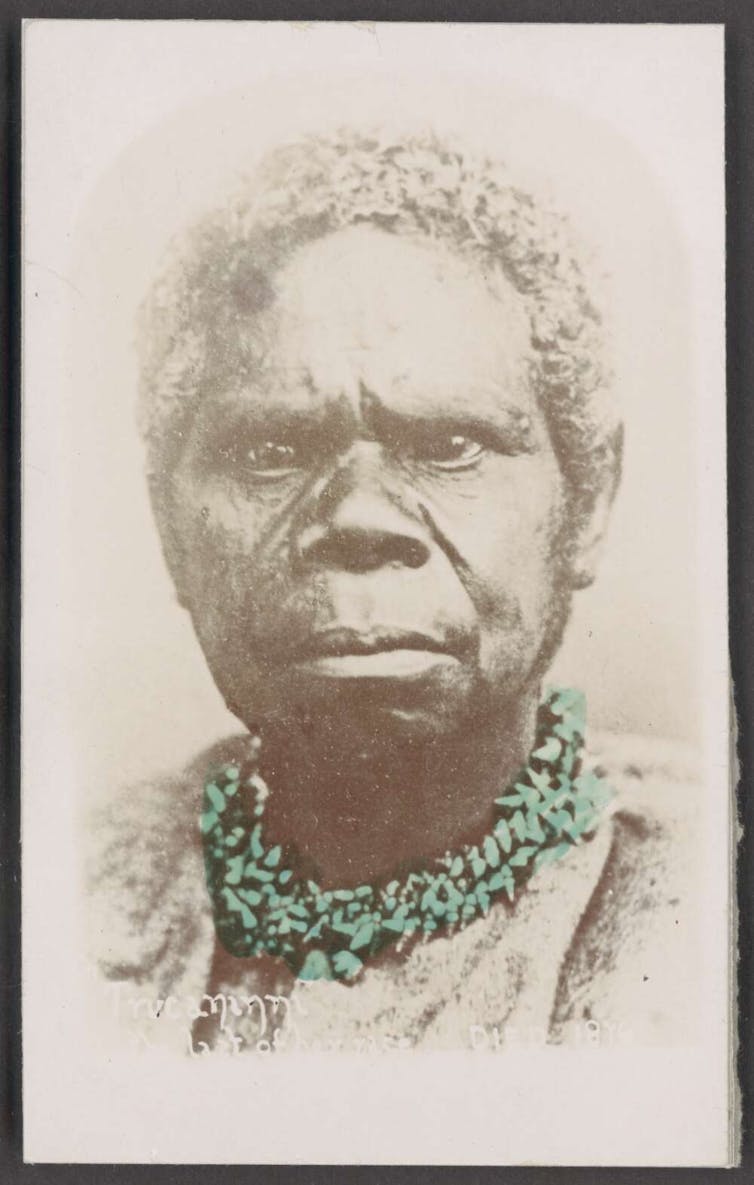

For many years the truth was either deftly avoided or consciously suppressed. Aboriginal families kept alive their own memories of those terrible times, even if they were not necessarily aware of the broader national story.

A pioneer Queensland pastoralist who had worked for years with Indigenous stockmen came to appreciate the continuing legacy of the violent early years, or what he termed ‘the remembrance of the blood red dawn of their civilisation’.

Once anthropologists and linguists began to work in First Nations communities in the 1930s and 1940s, they too learnt how vigorously alive were memories of historical violence. They should perhaps have known more about it but often didn’t. Their education had let them down.

The violence, the ‘line of blood’, was well known in colonial society. It had been discussed and argued about from the earliest years in New South Wales and Tasmania. The central points of contention still confront us.

Was it an inescapable companion of colonisation? Was it a case of forced appropriation or none at all? Were all the colonists, including those with no experience of the frontier, complicit by remaining in Australia? Did the new societies bear a collective moral burden? Or was it necessary to distinguish the culpability of free settlers from that of the convicts and the Australian-born children?

‘This right to Australia is a sore subject with many of the British settlers,’ a Victorian pioneer noted in the 1840s, ‘and they strive to satisfy their consciences in various ways.’

At much the same time, the South Australian settler Francis Dutton thought that the claims of the blacks were ‘superior to ours’, although his contemporaries were ‘too eager on all occasions … to persuade ourselves that such is not the case’.

The Aboriginal question ‘gave rise to more argument’ than any other matter in Queensland in the 1860s according to the editor of the Rockhampton Bulletin.

Running close to the colonial debate about the morality of settlement was the unavoidable question of frontier conflict. Was it a form of warfare even if of quite a distinctive kind? Or were the pioneer settlers murderers? Were they heroic pathfinders or criminals?

There were very few court cases where such questions might have been assessed and therefore publicised. On the other hand, war and homicide were matters widely understood, each with their own place in the popular mind. So there was no consensus, no resolution that has been passed down to us. We have to resolve the matter ourselves.

Our most important war

There were always settlers who opted for warfare as the way out of the moral quandary of colonisation. And many of the military men who lived and worked in NSW and Tasmania talked openly of war. Many of them were career officers with battle experience.

It is not surprising therefore that many of the historians who have rewritten the history of frontier conflict over the last 40 or so years have followed in their wake. More to the point is that since at least 1990, Australia’s professional war historians have both accepted and promoted the idea that frontier conflict must be considered alongside Australia’s overseas wars.

But that can only be the start of a significant transformation in the way we think about both the frontiersmen and the warriors of the First Nations who confronted them all over the continent.

Rigorous truth-telling will be of critical importance here, but that can only be part of the required transformation. The telling must be heard and treated with gravity. Changes in traditional accounts of national history will have to be accepted.

Above all, we must bring together the ways we think about and commemorate the two forms of national war-making – the many overseas campaigns on the one hand and the war fought in Australia for the ownership and control of the continent on the other.

The truth-telling will have achieved its ultimate purpose when Australian children are able to consider that the long-running and widespread conflict that accompanied Australian life for 140 years was arguably our most important war.

Aboriginal people on the frontier

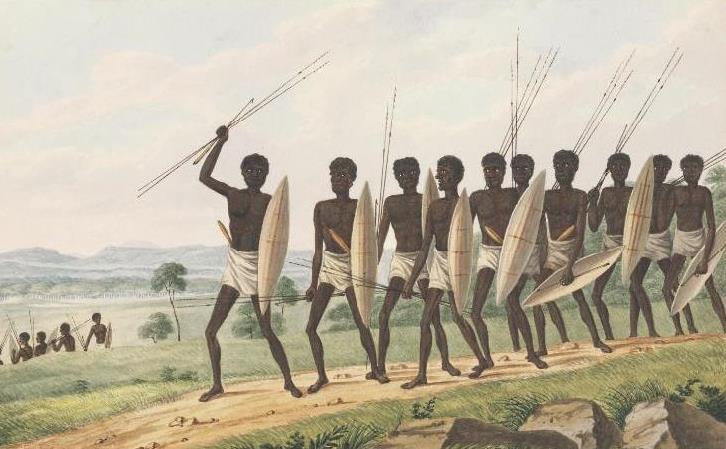

But how can two such disparate narratives be spliced together? It will clearly take time and will need steady and persistent commitment. Many small threads will have to be engaged. Complexity will have to replace simple sagas of heroic settlement. For instance, few people appreciate that Aboriginal people participated from the earliest years in the outward thrust of the frontier.

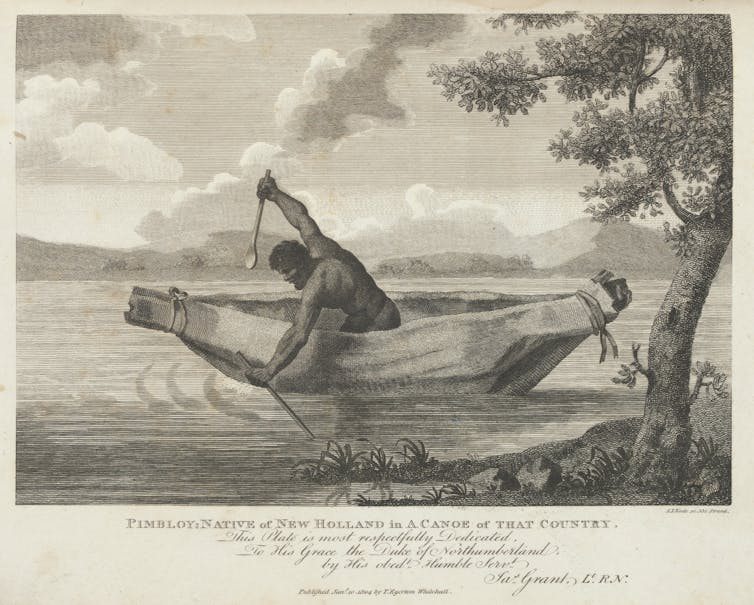

The first expeditions that pushed out into the interior were invariably accompanied by Aboriginal escorts who acted as guides and diplomats. They were able to find their way across country, discover water, track straying horses, hunt and gather food. They could quickly construct temporary shelters and simple bark rafts to ford rivers.

Their value was so obvious that it became a settled custom for expeditions, both private and official, to recruit young men and women to act as valued auxiliaries. When the squatters surged out into the interior of NSW, Aboriginal people went with them and quickly developed the skills that made them valued and competent stockmen and women.

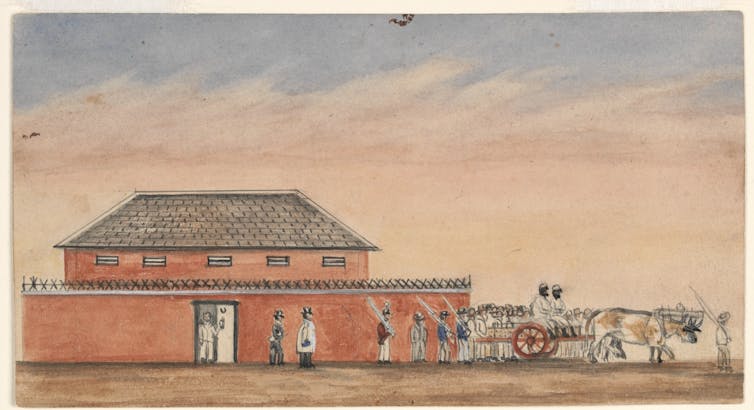

Children, often enough kidnapped, were taken along as personal servants and eventually sexual partners. Once the vast savannah lands of the tropical north were occupied, local Aboriginal people became the mainstay of the workforce, given the scarcity, cost and unreliability of white labour.

They were an essential component of the successful establishment of the northern pastoral industry and, consequently, the principal claim the settler Australians could make to prove they were in effective occupation of as much as a quarter of the continent.

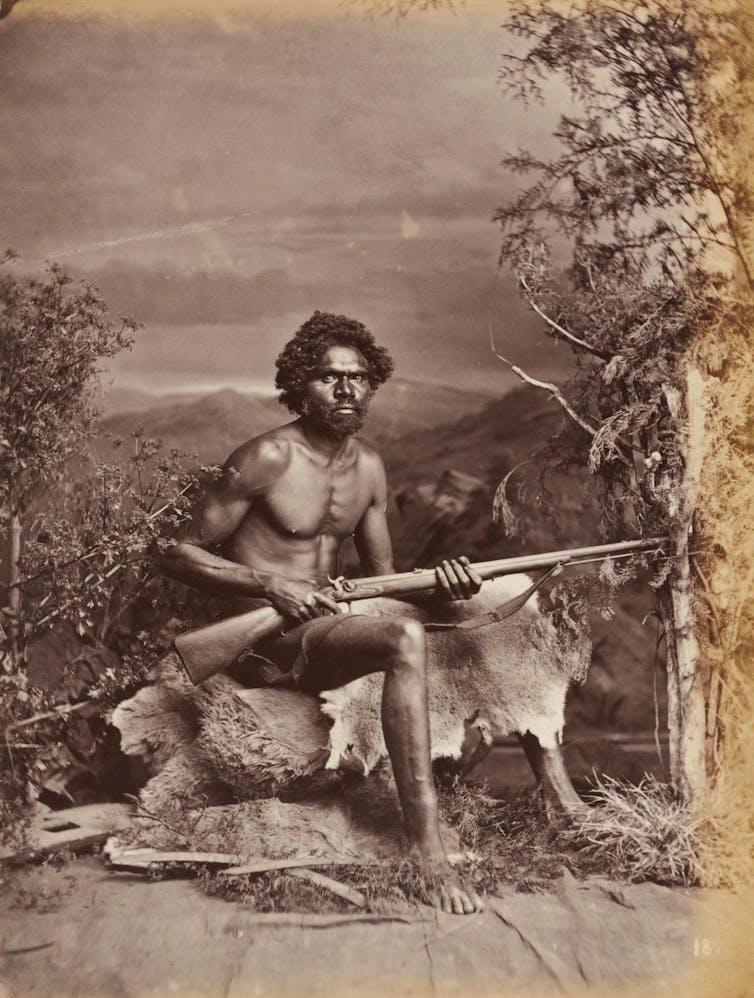

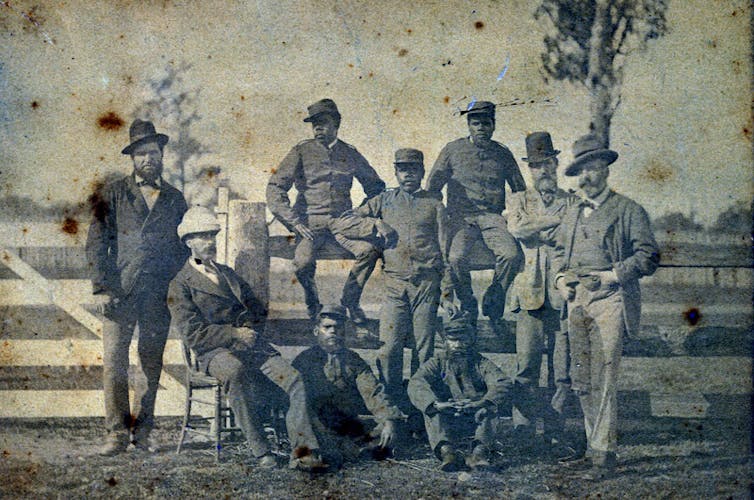

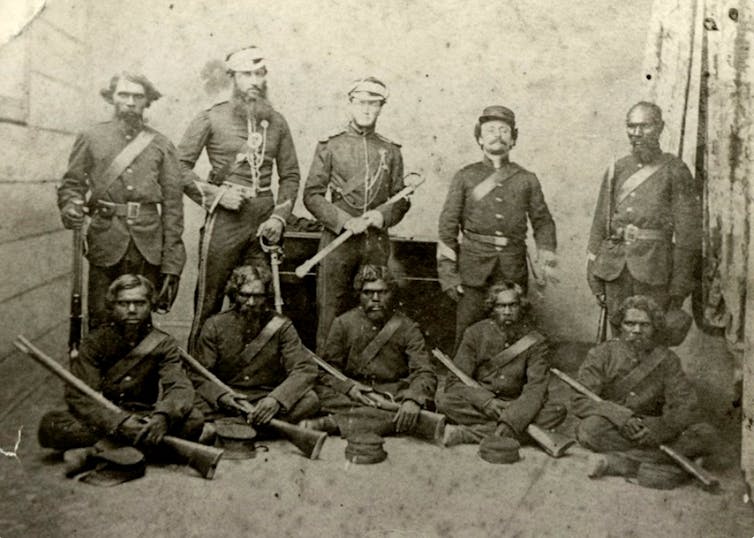

The same skills made young Aboriginal men ideal troopers for native police forces in Victoria, NSW and particularly Queensland. Their bushcraft was essential to the success of the northern force in crushing the resistance of the First Nations over a vast area of the colony. They were also much cheaper to maintain than a comparable force of European troopers.

There seems to be no precise record of the number of Aboriginal young men who served in the force. In his history of the Native Police, The Secret War, Jonathan Richards listed just over 250 white officers who spent varying periods of time out in the field. But he provided no estimate of the equivalent number of Indigenous troopers.

There must have been hundreds and possibly as many as a thousand. The conclusions that follow from this are compelling. The troopers almost certainly killed more Aboriginal people than the settlers.

In total, they may have been responsible for up to a quarter of all deaths in the frontier wars all over Australia. This too has to be part of our truth-telling.

The response of many people when this matter is raised is to express amazement that the troopers could shoot their own people and assume they must have been coerced into killing. But the critical point is that the idea that the First Nations were members of one race or one people was a European one and had little bearing on the situation on the ground.

The young troopers were invariably campaigning far from their own homeland in country previously unknown among people foreign to them. And the locals were people to be feared. If the troopers were caught away from their detachment they would almost certainly have been killed, and this kept them together as much as the discipline imposed by white officers.

So whether as paramilitary troopers, workers, trackers, guides, servants and sexual partners, many hundreds of Aboriginal Australians were participants in the outward thrust of the frontier.

The implication is inescapable. Many Indigenous families have ancestors who were pioneers in the precise meaning of that term, both black and white, whether recognised and acknowledged or not.

White fear

Truth-telling allows us to weave new stories and to make old ones richer while, at the same time, more complex. This is particularly true when it comes to our understanding of frontier warfare. The common view is that the Aboriginal peoples were, for much of the time, passive victims of European brutality.

Such ideas help explain the one-time common view that the Aboriginal peoples were quite unable to put up a spirited resistance of the kind seen in New Zealand and North America, that they were ‘pathetically helpless’ in their response to the invaders of their homelands.

Such opinions, common among professional historians until the 1960s, underpinned the idea that we had a uniquely peaceful history. Since then, the violence of the frontier has flooded back into the national story. But the overwhelming idea of Aboriginal people as victims of irresistible violence has lived on as a powerful political weapon, readily mobilised to assault the conscience of white Australia. Still, as is often the case, good politics makes bad history.

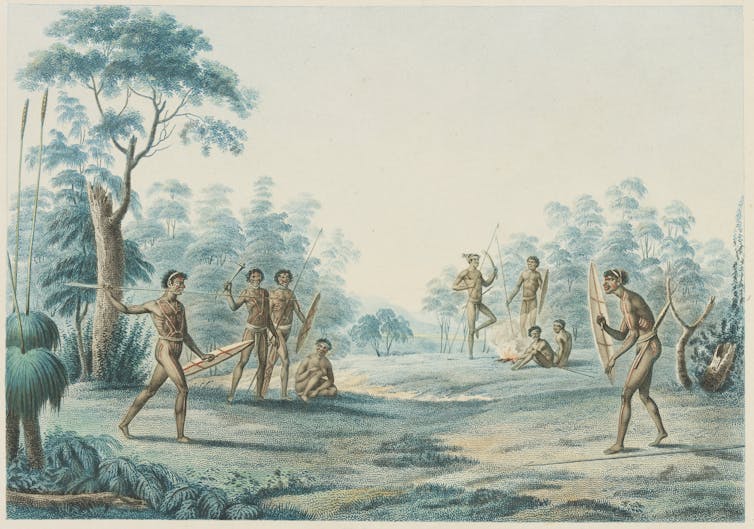

A few days’ research among the documentary records of the colonies would dispel these ideas. It was understood at the time that white fear was overwhelmingly important. The brave frontiersmen were terrified of the Aboriginal people. The evidence for this will be found everywhere.

A Sydney Morning Herald journalist who toured North Queensland in the 1880s concluded that ‘mere wanton slaughter would be unknown if the natives were not feared so much’.

Some years later, on the other side of the continent, the government resident at Roebourne reported that the ‘fears of whites are more the cause of disorder than the aggression of blacks’.

This should come as no surprise. In most frontier districts the invading force was spread very thin. The small parties were almost everywhere outnumbered by resident bands. They were in country they knew little about. It looked, felt and smelt dangerously exotic. They had no maps and had no idea where Aboriginal parties periodically disappeared to.

The people they were displacing had a profound knowledge of their own land. They were in many cases taller, stronger and better nourished than the Europeans, who got by on a very limited diet. And they were hunters trained from childhood.

They could track the intruders and stalk them without being seen or heard, and throw their spears with lethal force and accuracy. Guns were important, particularly late in the 19th century when men on the frontier carried revolvers and high-powered repeating rifles.

But it was the horse that had tipped the balance in the invaders’ favour. Their power, speed and endurance made all the difference on the vast open plains of inland Australia.

When speaking in their own defence, frontiersmen insisted that they acted in response to Aboriginal aggression. A typical argument was advanced by the editor of the Hodgkinson Mining News who wrote in 1877:

‘It is not the rule that the white men are the aggressors. The first settlers came peaceably onto the land they had got by right from the Crown, and no sooner had they done so than the hostilities of the natives compel them to adopt not merely defensive but offensive measures.’

It was special pleading but there is no doubt the frontiersmen, like invaders anywhere, would have preferred to achieve a bloodless usurpation.

The editor’s comment nudges us, however, towards an enhanced understanding of the frontier wars. It was Aboriginal resistance that determined where and when conflict broke out and for how long it lasted. And that was clearly the result of innumerable political decisions, made often at band level, about how to respond to the white men.

Initially there was a choice of attempting to accommodate the intruders, avoiding them altogether or spying on them in order to gather information about them. The fateful decision to begin forceful resistance often took some time.

It may have begun with a compelling desire to carry out a revenge mission aimed at a particular individual for what would have been a crime in traditional society – the kidnapping and rape of a kinswoman, for instance.

From that point on, violence spiralled out of control. Attacks on vulnerable white men were often combined with the killing of sheep, cattle and horses; the burning of huts and crops; and the pillaging of undefended camp sites.

The fighting continued until the Aboriginal bands decided that the cost they were paying was too high. Once again there must have been intense and urgent debate about how to bring the merciless killing to an end.

And even then, the question of how to negotiate a capitulation must have occupied time and thought. But everywhere, sooner or later, the survivors were, in the victors’ words, ‘let in’ to pastoral stations, mining camps or rudimentary townships.

Not everyone was willing to surrender, and small parties of what the white men called myalls continued to live independently in remote areas of their homeland.

‘We are at war with them’

The explorer Edward Eyre was one of the people who was able to look beyond the conventional view that the warriors were dangerous but lacking martial virtue. He observed that:

‘It has been said, and is generally believed, that the natives are not courageous. There could not be a greater mistake … I have seen many instances of an open manly intrepidity of manner and bearing, and a proud unquailing glance of eye, which instinctively stamped upon my mind the conviction that the individuals before me were very brave men.’

From an admiration of Aboriginal bravery it required a further step to regard the warriors as heroic patriots defending their homelands, although that was one too demanding for most colonists. It required an even-handed approach difficult to sustain in times of conflict and that threatened to undermine the legal and moral foundations on which the Australian colonies rested.

It was the war in Tasmania in the 1820s that produced one of colonial Australia’s most provocative manifestos. It was printed in a Launceston newspaper at the very end of five years of conflict. The author J.E., assumed to be the young surveyor James Erskine Calder, posed what he called some solemn questions about the islands’ Aboriginal peoples. He declared:

‘We are at war with them: they look upon us as enemies – as invaders – as their oppressors and persecutors – they resist our invasion. They have never been subdued, therefore they are not rebellious subjects, but an injured nation, defending in their own way, their rightful possessions, which have been torn from them by force.’

Given the time that it was written that was provocative enough. But J.E. followed the logic of his position much further arguing:

‘What we call their crime is what in a white man we should call patriotism. Where is the man amongst ourselves who would not resist an invading enemy; who would not avenge the murder of his parents, the ill-usage of his wife and daughters, and the spoliation of all his earthly goods, by a foreign enemy, if he had an opportunity? He who would not do so, would be scouted, execrated, nay executed as a coward and a traitor; while he who did would be immortalised as a patriot.

‘Why then shall deny the same feelings to the Blacks? How can we condemn as a crime in these savages what we should esteem as a virtue in ourselves? Why punish a black man with death for doing that which a white man would be executed for not doing?’

They were challenging questions then. They remain so today.

Warriors as patriots

I came across J.E.’s letter years ago and have used it in several books. I have also read it to audiences in many parts of Australia. In almost all cases people have found it a complete surprise. They are amazed that a colonist would publish such an enlightened letter almost 200 years ago. They correctly assess that his questions still confront and challenge us.

Can we, by which I mean Australia as a nation, regard the First Nations’ warriors as patriots? Can we immortalise their heroic defence of their homelands? We have a great deal of experience when it comes to remembering and commemorating our citizens who have died in conflict. No expense is spared. The phrase ‘Lest We Forget’ is surrounded by a sacred penumbra.

But do we want to allow the heroes of the First Nations to join the chosen ones? Do we want to extend to them the honours we award to the war dead from all our overseas engagements?

Do we want to honour them with a place in the nation’s pantheon? Do we want to share the honours we have hitherto preserved for our warriors who fought on foreign soil? See it as a national priority? If the answer is yes, what would be required?

Do we want to share the honours we have hitherto preserved for our warriors who fought on foreign soil? See it as a national priority? If the answer is yes, what would be required?

Memorials to our overseas wars can be found all over the continent, even in the smallest and most isolated villages. In his book Sacred Places, Ken Inglis estimated that there are more than 4,000 war memorials of one kind or another.

And then there are the tens of thousands graves cared for by the War Graves Commission in Australia and many places overseas. During the carnival of first world war commemoration we witnessed between 2014 and 2018, old monuments all over the country were refurbished and avenues of honour replanted.

A new museum costing $100 million was built in northern France to commemorate the achievements of the AIF. Meanwhile the Australian War Memorial had achieved an unparalleled place in national life. Visiting schoolchildren are taught that it is where they must go to understand what it means to be an Australian.

It is now described by the director of the institution as the ‘soul of the nation’, a view endorsed by Defence Minister Linda Reynolds, who has said the memorial embodies ‘the soul and the psyche of Australians’. The government has recently granted it half a billion dollars for a highly controversial building program.

The memorial’s apotheosis has been achieved during the years when many aspects of Australian history were transformed and in particular our new understanding of the magnitude of the frontier wars.

But rather than embrace the new historiography, the memorial has turned its back on it, despite the highly relevant research and writing of many of the Canberra-based war historians, some of whom have actually worked inside the institution.

The reason for this recalcitrance has never been convincingly outlined. The most common explanation is that while frontier conflict has been accepted as part of the national story, it should come under the aegis of the National Museum rather than the War Memorial.

A new national museum

The War Memorial’s implicit disrespect for the warriors of the First Nations represents a case of profound moral failure. It has let us all down. It was made worse by a parallel political failure as a consequence of the complete lack of interest in the subject from all sides of the federal parliament.

The problem could have been resolved so easily. One formal ceremony would have woven the two traditions together. The placing of a tomb for the unknown warrior in the heart of the memorial next to the grave of the unknown soldier would have been an event of immense national importance, a symbol of respect, inclusion and reconciliation. What a difference that would have made to the way we feel about ourselves!

The War Memorial’s implicit disrespect for the warriors of the First Nations represents a case of profound moral failure.

There seems little chance now that this will ever happen. We will have to persist with two separate stories of war. The inescapable implication is that the nation itself is deeply divided, its soul bifurcated and located in different places.

But if the two histories are to be told in different ways and in distinctive institutions, they must be given equal resources to not only continue the truth-telling, called for in the Uluru Statement from the Heart, but to enable the truth to be proclaimed and illustrated in a compelling way.

The call must be: ‘If not inclusion then equality’.

What is clearly required is a new national museum dedicated to the frontier wars and supported with the same level of funding that is received by the War Memorial.

It will be expensive, but if $100 million can be lavished on building a museum dedicated to a few years of fighting in France, that is the least that should be expected to establish an institution here dedicated to the story of the conflict experienced in all parts of the continent over 140 years.

The new institution could then provide advice and encouragement to regional organisations to consider ways to research and commemorate the war fought within their own traditional boundaries.

Not every community would necessarily respond, but the variety of the chosen manner and form would likely provide an exhilarating experience for locals and visitors alike. In some places the descendants of the white pioneers might be invited to participate in the commemoration.

Museums and monuments are important instruments to both remember the past and to engage in truth-telling.

This is an edited extract from Truth-Telling: History, Sovereignty and the Uluru Statement by Henry Reynolds, New South Books.![]()

Henry Reynolds, Honorary Research Professor, Aboriginal Studies Global Cultures & Languages, University of Tasmania

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.