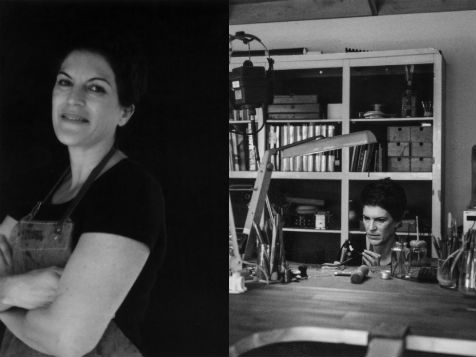

Painter Ella Whateley by Rohan Thomson

Artists create experiences that help us understand our world, each other and ourselves more deeply than we could ever dream of doing alone. This is the value of our musicians, writers, poets, visual artists, actors, dancers, digital artists, designers, and the list goes on.

There is much good news in the arts. As a society we are coming to recognise the value of the work of artists both in itself and for its impacts on innovation, health, education and on our collective identity. Over recent decades Australians’ participation and expenditure in the arts has risen steadily. Thankfully, philanthropic support for the arts in Australia is also rising.

More recently we know some governments have stumbled in their support for the arts, in particular for individual artists and for small to medium arts organisations. A recent report from the National Association for the Visual Arts observes that removal of significant funding from the Australia Council for the Arts by the Australian Government in 2015 ‘resulted in 50% of previously funded visual arts organisations losing operational support…’. The recent news that the majority of this funding will be restored to the Australia Council is welcome, even though the arts sector will take some time to get back to full speed, and a good number of projects previously in development may never mature.

Arts funding at the State and Territory level sporadically suffers from a similar unpredictability. Campbell Newman’s mining of Queensland’s arts budget in 2012 scarred the arts across much of the State. More recent cuts to ACT Government funding for arts projects, announced in December 2016, sent tremors through an arts community still sensitive from the painful fallout of cuts to the Australia Council. An immediate outcry found genuine engagement and a quick rethink by the ACT Government. Record new funding and welcome improvements to the grants process itself are promised in the next ACT budget.

Further-a-field, President Trump’s plan to eliminate the National Endowment for the Arts and similar bodies further deepens the darkness that is stretching over the future of public culture in the United States.

In the wake of these worrying turns and turn-a-bouts in public support for the arts, Walkley-awarded photojournalist Rohan Thomson began a new project.

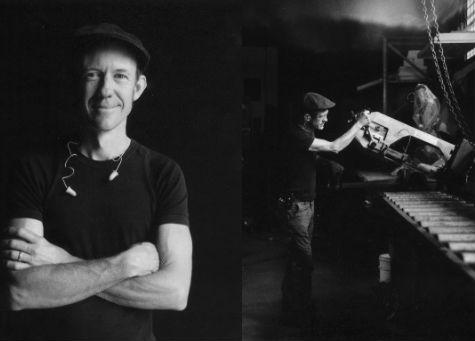

Sculptor Geoff Farquhar by Rohan Thomson

In the slow news days of early January 2017, in a brief gap between stories away from his salaried lens, Thomson began to contact artists who work in the Canberra region. He asked them if he could photograph them at work in their studio.

Thomson had started playing about with a modified 1960s Polaroid Land Camera. In contrast to the high performance digital servant he uses day-to-day this camera is a limping thing of the past. Modified by hand to take packs of peel-apart Polaroid film, it produces unpredictable results. As the film is scarce, Thomson shoots just two or three images in a sitting. Each is a unique object so surface imperfections, anomalies in exposure and compromised compositions are par for the course. Thomson’s Polaroids bring the imperfect, wet-chemical past of instant photography to the fore. They are the photographic equivalents of a loose charcoal sketch or a raku pot.

Each of Thomson’s Polaroid portraits is presented as a diptych. In the left hand image an artist stands, face to camera, in front of a dark backdrop. We are invited to look through Thomson’s lens deep into their eyes. In the right hand image we see the same artist at work in their studio. They might be blowing glass, inking a printing plate or working a lathe. Invariably their eyes do not meet ours.

These intimate portraits self-consciously break from the norms of contemporary digital press photography. Off duty, Thomson, returns the photograph to the status of a unique and fragile object, an imperfect chemically-stained square of paper. Off duty, he eschews the camouflaged choreography of the press photograph, preferring to present his subjects alternately as removed from their environment against a dark backdrop, and then immersed in their environment, eyes away from the camera, absorbed in their creative work.

Thomson’s work might have us recalling the work of German photographer August Sander begun ninety years ago. It became a body of work that would culminate in arguably the most influential photobook of our era, ‘Faces of our time’. The book contains 60 portraits from Sander’s extended series ‘People of the 20th Century’, itself divided into seven sections: The Farmer, The Skilled Tradesman, The Woman, Classes and Professions, The Artists, The City, and The Last People.

Jewellery maker Sabine Paga by Rohan Thomson

This system of classification reveals much about Weimar Germany and the artist’s world view. Today Sander’s project is regarded as an artist’s attempt to come to terms with an established social order undergoing irreversible change.

Unlike Sander, Thomson does not set out to catalogue a cross-section of our society. Rather he gives visual form to the value he recognises in the labour of our region’s artists.

Perhaps Thomson is calling on us to remember that our artists are essential to our capacity to truly know ourselves – and that they are vulnerable. Thomson’s images are an intimate activism that will not be televised.

The makers by Rohan Thomson

The Photography Room, 21 Wentworth Avenue, Kingston Foreshore ACT

24 March – 30 April 2017