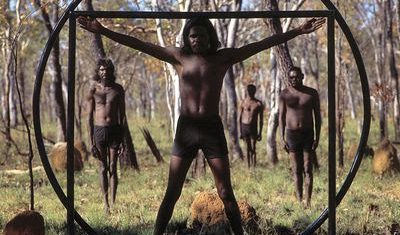

The ability of music to communicate, sustain knowledge and support feelings of affiliation is widely acknowledged. Its ubiquity and diversity worldwide demonstrate its potential to help humanity adapt and thrive in different times and places. Nowhere is this more evident than in Australia, home to the most long-standing, landscape-based performance traditions in the world. Aboriginal songs connect people, language, knowledge and country – that ‘nourishing terrain’ that is alive and intertwined with Aboriginal identities and knowledge systems.

Indigenous Knowledge – connected by song

In this extract from 'Indigenous Knowledge – Australian Perspectives', the authors explore the importance and power of music and its interconnected practices.

28 Nov 2024 14:07