Western Arnhem Land, Northern Territory, has a remarkable range and number of rock art sites, rivalling that of Europe, southern Africa and various parts of Asia. Several thousand sites have been documented and each year new discoveries are made by various research teams working closely with local Aboriginal communities.

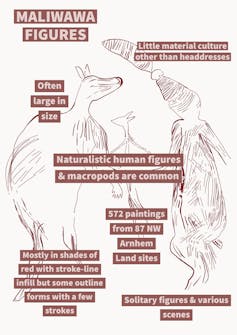

Today, in the journal Australian Archaeology, we and colleagues introduce an important previously undescribed rock art style. Consisting of large human figures and animals, the style is primarily found in northwest Arnhem Land, and has been named Maliwawa Figures by senior Traditional Owner Ronald Lamilami.

We recorded 572 Maliwawa paintings at 87 rock shelters over a 130-kilometre east-west distance, from Awunbarna (Mount Borradaile) to the Namunidjbuk clan estate of the Wellington Range, a region home to unique and internationally significant rock art of various types.

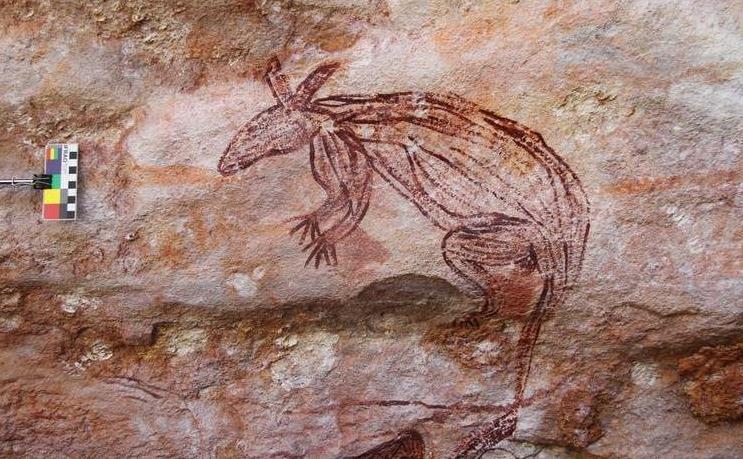

Maliwawa Figures consist of red to mulberry naturalistic human and animal forms shaded with stroked lines. Occasionally they are in outline with just a few strokes within. Almost all were painted but there is one drawing.

The figures are often large (over 50 cm high), sometimes life-size, although there are also some small ones (20–50 cm in height). Various lines of evidence suggest the figures most likely date to between 6,000 to 9,400 years of age.

Animal-human relationships

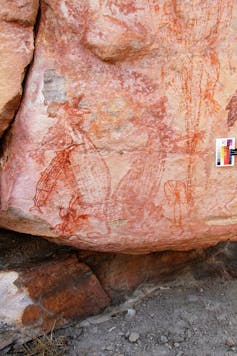

In the Maliwawa paintings, human figures are frequently depicted with animals, especially macropods (kangaroos and wallabies), and these animal-human relationships appear to be central to the artists’ message. In some instances, animals almost appear to be participating in or watching some human activity.

Another key theme is a male or indeterminate human figure holding an animal, often a snake, or another human figure or an object.

Such scenes are rare in early rock art, not just in Australia but worldwide. They provide a remarkable glimpse into past Aboriginal life and cultural beliefs.

Maliwawa animals are usually in profile. Some macropods are shown in a human-like sitting pose with paws in front, resembling a person playing a piano. Depictions of animal tracks (footprints) and geometric designs are rare.

Macropods, birds, snakes and longtom fish are the most frequent animal subjects, comprising three quarters of total fauna. But, more generally, mammals are most common.

There are seven depictions of animals long extinct in the Arnhem Land region, consisting of four thylacines and three bilby-like creatures. At one Namunidjbuk site there is a rare depiction of a dugong.

A third of human depictions were classified as male because they have male genitalia depicted. Females, identified because breasts were shown, are rare, comprising only 5% of human depictions. Almost 59% of human figures could not be determined to be either male or female because they lack sex-specific characteristics.

Human figures generally have round-shaped or oval-shaped heads; some have lines on the head suggestive of hair. 30% of human figures are shown with headdresses, of which there are ten different forms. The most common is a ball headdress, followed by oval, cone and feather.

Maliwawa males are usually in profile and often have a bulging stomach above a penis. A few Maliwawa females are also shown with an extended abdomen.

National significance

Most Maliwawa Figures are in accessible or visible places at low landscape elevations rather than hidden away, or at shelters high in the landscape. This suggests they were meant to be seen, possibly from some distance. Often, Maliwawa Figures dominate shelter walls with rows of figures in various arrangements.

We first found some of these figures during a survey in 2008-2009 but they became the focus of further field research from 2016 to 2018.

In Australia, we are spoiled with rock art — paintings, drawings, stencils, prints, petroglyphs (engravings) and even designs made from native beeswax in rock shelters and small caves, on boulders and rock platforms. Often in spectacular and spiritually significant landscapes, rock art remains very important to First Nation communities as a part of living culture.

There are as many as 100,000 sites here, representing tens of thousands of years of artistic activity. But even in 2020, new styles are being identified for the first time.

What if the Maliwawa Figures were in France? Surely, they would be the subject of national pride with different levels of government working together to ensure their protection and researchers endeavouring to better understand and protect them.

We must not allow Australia’s abundance of rock art to lead to a national ambivalence towards its appreciation and protection.

The Maliwawa Figures demonstrate how much more we have to learn from Australia’s early artists. And who knows what else is out there waiting to be found.

![]()

Paul S.C.Taçon, Chair in Rock Art Research and Director of the Place, Evolution and Rock Art Heritage Unit (PERAHU), Griffith University and Sally K. May, Senior Research Fellow, Griffith University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

_Encounters-in-Reflection_Gallery3BPhoto-by-Anpis-Wang-e1745414770771.jpg?w=280)