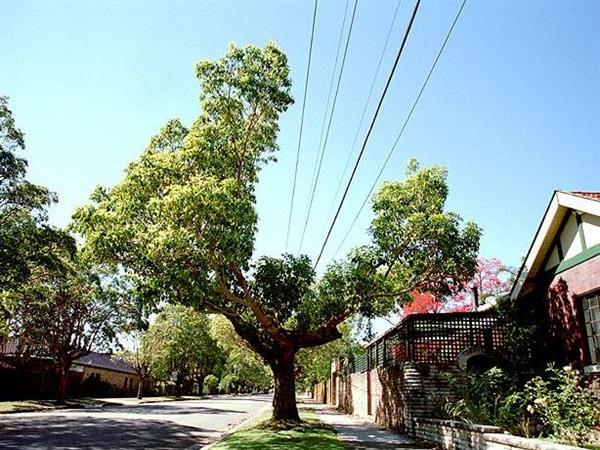

Artist Garry Trinh refers to the trees that Councils plant and are locked in by footpaths, as ‘urban bonsai’. Despite the difficult conditions, they adapt, finding new forms that are hardy and beautiful. It’s a powerful metaphor for the arts ecology, and one that fits resilient arts leadership developing in the face of increasingly financial pressures.

As the chair of a recent SAMAG (Sydney Arts Management Advisory Group) panel presented in Newcastle (NSW), I was surprised by the optimism of the four arts managers on the panel, who seem every bit as adaptable as Trinh’s oddly shaped trees.

Amy Hardingham, Co-Artistic Director, Tantrum Youth Arts, set the tone: ‘Always something comes through; it’s always so bloody bleak and dark, but then something comes through. I don’t let myself buy into it.’

Surviving the tough times

One of the great quotes that has passed my desk this year was that working in the arts at this time is like swallowing a live cat, suggesting the constant anxiety and stress of having a cat clawing inside you.

Hardingham knows that feeling first hand. In 2011 Tantrum Youth Arts lost its organisation funding from the Australia Council for the Arts.

‘Over the last four years, when we have repeatedly done the math, the gap is always the same – that amount we lost from AusCo. And even though we restricted the company and our operations, it is so hard to move forward without that money.

‘That government funding is essential because it is the only funding you have outside your programming. When you lose that it becomes really tough to keep the company going … for two years we nearly closed.’

Hardingham said they did a number of things to survive. ‘In early years it was literally penny pinching; we never put in a receipt for petrol or a pen – the staff do subside so many arts organisations – and that is one way to keep going without that core funding.

‘We also changed the way we worked. Rather than have a large roster of casual workshop staff we moved to two teaching people on our staff to run more effectively.’ She added that the community of Newcastle was extraordinary in its support.

‘They heard our message when we said, “We need your help”. We rely very much on our workshops and their earning capacity; we rely on small local government grants and support from local industry, and we rely on people donating their time from a cake sale to crowdfunding.’

Garry Trinh’s Giant Bonsai – 33 Francis Street (2005); Courtesy the artist www.garrytrinh.com

One audience member from the sector said that they have survived the past two years by changing the questions you ask. ‘We find when we ask, “What do you need? How can we make ourselves useful to you? that works. But you have got to make sure that your company can respond to those questions and to have that agility to deliver on new partnerships.’It was an observation that McCarthy shared, moving from Perth to Newcastle: ‘The freedom to go and ask someone can I do something in your space is easier (in regional locations). And it makes sense – let’s pull together. There are amazing partnerships occurring here and that is how it is surviving.’

There was a consensus that by working together through difficult times resources could be shared and new audiences grown.

Looking for lost money

Like many, Hardingham said she ‘foolishly and arrogantly’ thought she could get the funding back with a bit of hard work.

‘I was mistaken; the landscape had shifted. That pie closes over and no matter how great you are, it is very difficult to get it back,’ she said. ‘We were lucky to have lost our funding in 2011 because we were already in there fighting when the landscape changed more recently. We didn’t have to stop and regroup – we ended up surviving.’

She said the role of Tantrum’s volunteer board was key in scrutinising “the books” in rethinking and restructuring the organisation’s operations. ‘They looked at every cent and how we could spend it better.’

‘The job is actually about money most of the time and relationships; you work with people a little bit more than the art sometimes,’ said Hardingham. ‘So you have to get that right.’

Tantrum Youth Arts was successful under Catalyst, funding a 3-year Trajectory Emerging Arts Program that offers emerging artists professional experience and that career boost, ‘something really needed here in theatre in Newcastle,’ added Hardingham.

Burnout in bleak times

The message from these regional arts managers was that leading a company was a huge personal commitment – the sweat and the tears that doesn’t appear on the balance sheet.

We are told in this new climate to be persistently innovative, to embrace philanthropy, to broker new and unexpected partnerships and to find new funding streams. All sound advice, but how do we reframe that rhetoric from a ground-roots position?

Hardinghams said: ‘You get knocked down. You build resilience by getting up again and again, to quote (90s British anarcho-punk band) Chumbawamba.’

Cadi McCarthy, Director Catapult Dance in Newcastle, said the greatest challenge to resilience is burn out. ‘I do not have a staff so I do the admin, I do the finances, teach the workshops at night – I am doing everything and it has become 24-hours.

‘Over time that will shift, and I understand why it is like that now, but the hardest thing for me is to keep going,’ she said.

Catapult Dance was founded in 2014, and despite being well funded in its first few years, that injection has gone into program rather than resources. She said the answer to sustaining that challenge is personal passion for what you are doing, without it you can’t survive.

Like McCarthy, both Jess Duncan and Gemma Parsons are also one-person operations.

‘It can be difficult to keep up morale as we have a really tight budget. I have all these dreams and things I want to accomplish – and can see how people would benefit from them – so it is difficult for me to keep up morale when I am trying to stretch the money,’ said Duncan.

Working with community in Moree in remote northern NSW, she said it was the little wins that make it worthwhile, and the community’s response give her that energy to persist.

Duncan and Parsons both work for the not-for-profit organisation Beyond Empathy, which was founded in 2004 to empower individuals and communities living with difficulty for change. Their website claims that ‘change is only possible over the long haul’, and that arts and cultural engagement is a pathway for that change.

Parsons admits that working in community is a bit of a challenge. Based in the Illawarra, she primarily works on developing film projects with community.

‘Sometimes it does feel like going one step forward and two steps back. You can’t control what is going on in the community or the politics that is happening. It’s very important to recognise your strengths and what you are bringing to things – for me it’s flexibility.’

Like McCathy, Duncan describes herself as a jack-of-all-trades. ‘I run the budget, plan our strategic directions, book venues, artist and accommodation, cook BBQ’s and make sure all equipment needed is on hand. The things that you look for in a partnership could be considered outside the box – like making connections through recycling materials.’

‘Being a sole employee it comes down to your ability to build relationships. I stalk a lot of people,’ said Duncan.

Personal resilience

Hardingham believes that today’s bleak times are not reserved exclusively for the arts. We only need look at the world’s conflicts or political state.

‘Yes we have just come through something terrible in terms of funding, but I get the feeling, and maybe it is from the echo chamber of the leftist-arty-social-media-stream, that there is an optimism there that comes from a desire to reflect and share stories and that is an opportunity,’ she said.

The way the arts community came together in the wake of last year’s funding cuts, a more recently art school closures, it is the strongest that the sector has banded together as a unified arts ecology.

It is not a new thing that the arts struggle; the new thing is how we face that challenge. ‘I am not scared to pick up a phone and make it happen. A lot of people get bogged downed in the detail and panicked by the crisis. I say to those around me, “Don’t worry about detail, that will happen later. I’m a fixer,’ said Hardingham.

She is of the camp of thinking that we become stronger, wiser and more dynamic when challenged – and the arts sector has always been challenged – so get on with the job.

Tantrum is soon to lose its home, the second time since Hardingham has been at the helm. He stresses the need to move is not a result of the mixed arts / shared resources space that the company current occupies with the Community Arts Centre, a model that continues to hold great hope for organisational sustainability.

But the need to find a new home is a tremendous pressure. ‘When you go every week to view a new space, with a new agent, constantly following leads it is very difficult but you have to remain positive; you have to believe something will happen. I have done it enough times to know that regardless how bleak it looks now I know in six months it will be OK.’

That push through and optimism was the walk-away message from this panel. Five local councils were represented in the audience. Those attending were strong in numbers and supportive, staying on to network with colleagues. These are not the signs of a bleak state of affairs.

This event was presented by Octapod and The Business Centre, and in partnership with SAMAG, as part of the Smart Arts program in Newcastle (NSW), December 2016.

Hero image: Shutterstock.