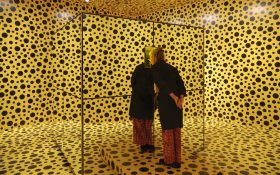

Public heavy metal sculptures are usually the domain of males but an exhibition of Bronwyn Oliver’s celebrates her long overdue accolades; Two Rings (2006) Photo Andrew Curtis

A new survey exhibition of work by the late sculptor Bronwyn Oliver curated by the eminent curator of Australian art Julie Ewington opened at TarraWarra Museum of Art recently, the latest in a string of recent exhibitions of women artists curated by female curators: Cindy Sherman by Ellie Buttrose for Brisbane’s Gallery of Modern Art; Anne Loxely assembling a group of female artists in Western Sydney; Kelly Doley rethinking the term feminism through the Cruthers Collection of Women’s Art (CCWA) at the Lawrence Wilson Art Gallery in Western Australia, and the touring blockbuster Making Modernism – an exhibition that survey’s the influence of artists Georgia O’Keefe, Margaret Preston and Grace Cossington Smith, put together by a female-weighted curatorium.

The pinnacle of this push was the announcement this year that Tracey Moffatt would represent Australia at arguably the most important international forum for contemporary art – the Venice Biennale. The pavilion will be curated by Natalie King and the commissioner for 2017 is patron Naomi Milgrom.

‘We are working as a female triumvirate of artist, commissioner and curator,’ said King, who is also mentoring Hannah Presley, the first Curatorial Assistant, First Nations to work on the Venice Biennale.

All female teams are highly visible at present, but why? Is there a conscious move to re-balance a former male dominance, or are we just seeing the outcome (finally) of equal visibility and billing?

Julie Ewington told ArtsHub: ‘I do think this “moment” is just a coincidence. Women curators curate women artists (amongst others) all the time. In fact, the curatorial profession is dominated, at least numerically, by women, so that’s pretty well inevitable.’

‘We have the knowledge, the expertise. It’s just that, in the past, women have not been sufficiently recognised. Now, talented and experienced women are in the curatorial and museum professions in droves.’

But King believes that it is not just knowledge and expertise, but also the capacity of women to care that contributes to their success as curators. In many ways curating is an extension of a traditional woman’s role, nurturing and enabling.

‘My role is to take care of the inner sanctum of artists and their ideas,’ said King, explaining the derivation of the word “curator” means ‘to take care’.

‘As curators, we negotiate the multifaceted and nuanced ambit of curatorial practice with an increasingly capacious role as raconteur, fund raiser, conduit, exhibition maker, writer, editor, budget manager, financial planner, timekeeper, arbitrator, public speaker, conjurer, press officer and the list goes on,’ she added.

The fact that women are adept at multi-tasking would serve the curatorial profession well then. This, however, is more than just a skills-based conversation. ArtsHub probed Ewington and King whether they felt feminism still held traction in our ever-changing pacey world, and how these exhibitions on women by women might help us to navigate a more balanced future.

King, who describes herself as an ‘ardent feminist’, believes that the topic of gender equality remains an urgent one.

‘I prefer to turn to relationships rather than a job (definition), and this pairing is reflective of how curator and artist can align in meaningful ways.

‘Working alongside Tracey Moffatt is intensely profound as her new work develops for Venice Biennale. She is unremitting in her focus and often quotes Louise Bourgeois to me: “I do, I undo, I redo.” I am both confidante and curator,’ said King.

‘We live in precarious and tumultuous times of seismic upheaval. It is not surprising that the feminist agenda is as urgent as ever. We only need to look at The Countess Report, complied by Elvis Richardson, for startling data on gender representation, which analyses hard evidence for gender equality in the visual arts.’

Read: Women are the winners

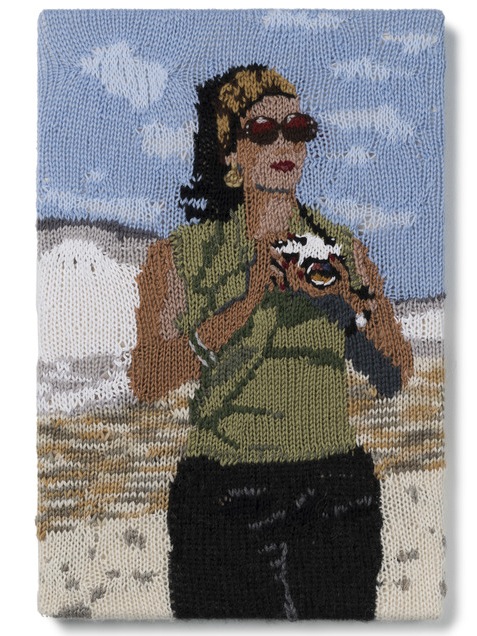

The way we make heroes of select artists is still an issue for many women artists, especially at an institutional level. Art itself can be an answer to this problem. King cited the young artist Kate Just whose hand-knitted Feminist Fan portraits immortalise women artists including Lynda Benglis, Pussy Riot, Louise Bourgeois, Guerrilla Girls, Sarah Lucas, Yoko Ono, Cindy Sherman and Tracy Moffatt. The knitted portraits of women are a witty counterpoint to usually male bronze bust.

‘She deftly stitches each self-portrait as an act of reverence: these are some female artists who I admire the most,’ said King.

Kate Just’s Feminist Fan #12 (Tracey Moffatt, Self-Portrait, 1999) 2015; Photo by Simon Strong, image courtesy Kate Just

Ewington added: ‘This advocacy is still important. It’s interesting that it’s been coming from younger artists – that tells us so much. There is certainly still resistance in this country – in some uninformed quarters, at least – to the notion that women artists are among the leading artists. But I think that this raw prejudice is, finally, beginning to fade.’

Her exhibition of over 50 works by Oliver speaks foremost of Oliver’s prowess and proliferation as a sculptor within a national and international frame; there is no feminist agenda.

‘There aren’t many artists who can offer a new way of looking at the world, but I think this is what Oliver does. It’s not beauty, so much, though that is certainly there. For me it’s something more like meditation – a moment apart. (And) to notice that in Australia we need to look closely at the work of our leading artists, and to do this regularly.’

Whether that curatorial sensitivity between Ewington and Oliver is a result of a compatibility influenced by gender, material or philosophy is ultimately irrelevant to Ewington. The responsibility to curators is simply to notice and enable leading artists, whoever they are.

Brownyn Oliver in her studio; Photo Sonia Payes

New tone to gender conversations

A curator at that coalface of contemporary feminism is Gemma Weston of the Cruthers Collection of Women’s Art (CCWA). She described the collection as a ‘feminist project’ but, like Ewington, she was quick to add that that doesn’t necessarily mean that the work the collection holds is feminist work, or that work made by women is automatically feminist.

Weston, in fact, believes that the practice of curating requires finding a way to work pragmatically with contradiction. She recently showed a new work to the collection by Kelly Doley, Things Learnt About Feminism, which explored that scale and scope of definitions surrounding feminism today.

Read: Grappling with feminism’s contradictions

‘There are artists held in the collection who fought against the perception of their work in terms of gender, and I think that a lot of women practicing art today would feel similarly. Women might act as feminists too, without exploring feminism directly as a subject,’ she said.

Ewington added: ‘The crucial thing is that not all these encounters will be explicitly feminist in content, but that feminism has consistently supported women artists, and, over the years, has illuminated curatorial practice in profoundly important ways – and not just for women curators.

‘What I’d like to see now in Australia is more women curators as the directors of the major state galleries or the National Gallery of Australia – to see that deep knowledge informing our great institutions and our cultural discussions,’ said Ewington.

This is not just a conversation reserved for the cities or global art centres. Earlier this year the young curator Sophie Rayner produced an exhibition to coincide with WOW 2016, Women of the World Festival, in remote Katherine (NT).

‘I am a young female curator, too young to have seen the first or second wave of feminism roll past, but old enough to know every word (and dance move) to each Spice Girls’ girl-power anthem, and think in contemporary western society the F-word [feminism] is outdated,’ she said.

Her aim was to explore the diversity of young women’s voices without applying what she sees as the obsolete lens of ideology. That’s What She Said included eight contemporary Australian artists spanning generations and geography.

Read: To Gen Y, feminism is the F-word

The numbers are looking better; and the exhibitions are looking less like placards and more like chapters in Australian art.The strongest way to advance such conversations within the visual arts is to curate more exhibitions like Tracey Moffatt, Bronywn Oliver and

Cindy Sherman, artists who are celebrated for their accomplishment regardless of gender.

The Sculpture of Bronwyn Oliver

TarraWarra Museum of Art (VIC)

19 November – 5 February 2017

O’Keeffe, Preston, Cossington Smith: Making Modernism

Heide Museum of Modern Art (VIC)

12 October – 19 February 2017

Queensland Art Gallery, 11 March – 11 June 2017

Art Gallery of NSW, 2 July – 2 October 2017

Tracey Moffatt

Australian Pavilion at the 57th Venice Biennale, 2017 (Italy)

Vernissage: 10 – 12 May 2017

Arsenale and Giardini Exhibition: 13 May – 26 November 2017