Institutional recognition in Australia towards British sculptor Dame Barbara Hepworth (1903 – 1975) is way past its due. Arguably the UK’s most well-known 20th century woman sculptor, Hepworth’s story is one of resilience, passion and rigour.

A very enlightened family allowed her, a single women in the 1920s, to pursue an artistic career where she studied sculpture at Leeds School of Art and then was awarded a county scholarship at the Royal College of Art. It was there she met Henry Moore (1898 – 1986).

Hepworth’s works are often compared to those of Moore, and their friendship and competitiveness lasted throughout their lifetimes. Until more recent decades, Hepworth’s achievements were always viewed as subordinate to Moore’s and she was often misrepresented as the his student during her early career.

As an artist who was both a mother and an abstractionist with a humanist lens, Hepworth’s private life was unconventional, divorcing her first husband John Skeaping in 1933 after falling for and later marrying abstract painter Ben Nicholson.

It’s with these interwoven connections in mind that the Heide Museum of Modern Art’s all-women curatorial team took a trip to the UK in 2018 with the vision of bringing the first Barbara Hepworth survey to Australia.

After a further two-year postponement, Heide has punched above its weight to open Barbara Hepworth: In Equilibrium, bringing together over 40 works from the Tate, the British Council, private collections and existing works in both Australian and New Zealand institutions.

Read: Your 2022-2023 summer exhibition planner

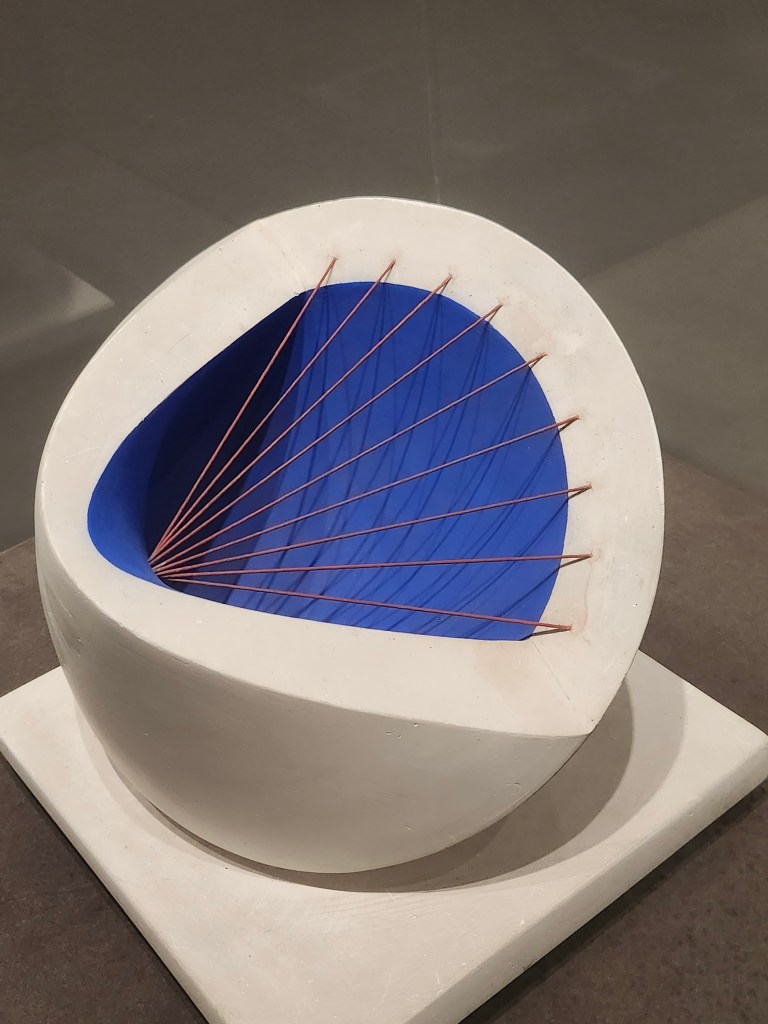

In the first gallery, a combination of early ‘pierced’ stone sculptures, string works of brass and bronze and the majestic hard-wood sculpture Corinthos (1954-55) present Hepworth’s experimentations in form and material, as well as the critical thinking embedded in her practice.

In works ranging from the vibrantly modernist Sculpture with Colour (Deep Blue and Red) (1940) to the egg-shaped and cross-stitched Spring (1966), colour and string signal something beyond sculpture to encapsulate the resonance between ourselves, each other and the landscape by which Hepworth was heavily influenced.

Head Curator Kendrah Morgan says: ‘From very early on Hepworth was a really strong proponent of direct carving, a technique pioneered by Constantin Brâncuși. She sought the tactility of the material and wanted to differentiate herself from women hobbyist carvers at the time, and [she was] choosing to carve on hard wood, which required a lot of skill and strength.’

Other significant works in the first gallery include early 1930s pieces such as Two Heads (1932) and Mother and Child (1934), which show the beginnings of Hepworth’s experimentation with the pierced forms. Morgan continues: ‘Henry Moore has always been credited with putting the ‘hole’ in sculpture, but actually Barbara Hepworth did it before him, and that hasn’t been acknowledged until the last couple of decades.’

In fact, most of Hepworth’s career success during her lifetime came in her late 40s, notably with her first public commission for the 1951 Festival of Britain. In 1950 she was invited to represent Britain at the XXV Venice Biennale, although that was following Henry Moore’s successful participation in 1948. Hepworth later expressed that she felt the works chosen for the show were too ‘discreet’ and ‘ladylike’.

Another moment of international achievement was marked by her celebrated win at the 1959 São Paulo Bienal where she took out its Grand Prize, ahead of fellow exhibitors from the British delegation, Francis Bacon and Stanley William Hayter.

Barbara Hepworth: In Equilibrium also brings together rarely seen works from local Australian collections, including Eidos (1947) and Figure (Oread) (1958), the only two Hepworth sculptures from the National Gallery of Victoria, and Two Forms in Echelon (1961) acquired by the Art Gallery of Western Australia in 1971.

Seamlessly at Heide: a note on co-design

Working with curators Kendrah Morgan and Lesley Harding, Melbourne-based architecture practice Studio Bright co-designed the exhibition, creating an atmosphere for Hepworth’s works to fit seamlessly into the gallery’s light-filled space.

Two Forms in Echelon sits directly in front of a large window opening out to Heide’s lush landscape, and this field of light is echoed to the right in a room that houses an early prototype of Single Form (1961). An updated version of this sculpture was developed in 1964 for New York’s United Nations building as a memorial to Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjöld, three years after his death in a plane crash. Hepworth had known Hammarskjöld as a friend and patron, and the sculpture, which still stands on the site, is her most significant public commission.

The Heide exhibition design draws on the works’ own play of light too, such as in the simmering copper and bronze of Forms in Movement (Galliard) (1956) and Head (Ra) (1971). The former is from the Wairarapa Cultural Trust Collection in New Zealand the the latter from the Art Gallery of South Australia.

Apart from the polished aesthetics, the exhibition also had to take into careful consideration different lighting and conservation requirements for the works on loan.

For example, Corinthos sits in a lush green-velvet draped room that absorbs both light and sound, while delivering a sublime encounter with the hardwood sculpture that Hepworth created after returning from a trip to Greece following the death of her first-born son. Within this space, Hepworth’s quiet philosophy is amplified through the marks, hand-made and chiselled, on the single piece of guarea, weighing over 400 kilograms.

Hepworth in her later years

Bringing the landscape into the gallery space aligns with Hepworth’s practice in her later years, when she often worked outdoors in the Cornish landscape, as exemplified by a film on view in the gallery.

As Hepworth got older her involvement with her sculptures only grew stronger – carving, painting and polishing while being embedded in nature.

She and Nicholson had moved to St Ives in Cornwall at the beginning of World War II and she remained there until her death in a studio fire in 1975. One of her last works showing at Heide is Group of Three Magic Stones (1973).

Unlike earlier works of textured plaster, rusted bronze and grainy wood, the work is a composition of geometric shapes in finely polished silver – almost un-belonging in the exhibition surrounded by works of more defined forms.

But as Morgan explains, it’s this sense of timelessness that has carried Hepworth’s works and achievements to the present day. ‘Later in her career Hepworth wanted her work to be almost talismanic and enigmatic. You don’t know if it was created today or many, many years ago and in that way it’s a symbol of endurance,’ she concludes.

Barbara Hepworth: In Equilibrium is on view at Heide Museum of Modern Art until 13 March 2023.