Snoösphere at The Big Anxiety.

‘Rancid perfume. Stinky babies. Sweaty clothes. Garlic hair. Human bodies putrefying and I think my own is beginning to smell,’ declares artist and researcher Dawn-joy Leong in her installation, An Olfactory Map of Sydney, at Customs House in Circular Quay.

At times confronting, at times funny, Leong’s graphic description of the assault of odours while travelling by bus forms a series of video monologues about her sensitivities to smells, sounds, light, colour, tastes and movement.

Leong is autistic and regularly feels overwhelmed due to hyper-sensory perception. This can trigger extreme reactions such as nausea, headache, vertigo and sometimes excruciating pain. Through Leong’s work, the viewer gets a real sense of how exhausting having such a heightened awareness must be, particularly in a world designed for “neurotypicals” – people who are typically wired or non-autistic.

I can’t breath. I’m feeling sick … Cacophony. Very dissonant. I’m terrified. The smells are mixing up and making my head hurt. I think I need to get off [the bus] right now.

An Olfactory Map (with Theodore Eu as video editor) is exhibited as part of The Big Anxiety, an initiative of UNSW and The Black Dog Institute. Through conversation, technology and art, the festival addresses issues of mental health, examining the major anxieties of our times, as well as the stresses and strains of everyday life.

A still from Dawn-joy Leong’s installation An Olfactory Map of Sydney.

Leong’s and other installations by autistic artists fall within the festival’s stream of Neurodiverse-City, which promotes an empathic culture of neurological differences (such as autism, ADHD, dyslexia or dyspraxia). The neurodiversity movement maintains that being neurodivergent (the opposite of neurotypical) is not a deficit, rather it is the result of natural variations in the human genome and is simply the way many people experience the world.

Diverse ways of being

“Art is for all, and should be made accessible to all,” claims Leong. She says autistic artists have much to offer the neurotypical realm, including a more “aware” way of responding to the world and detail-focused perception.

Contrary to the erroneous neurotypical belief that autism is a barren landscape of isolation, the autistic mind is a thriving ecology teeming with abundant detail, nuances, texture, tastes, sounds, images, smells, profound thought and imagination.

Another of Leong’s works, Clement Space in the City, is a sensorial refuge for those wishing to escape the barrage of city life. Leong describes the “need for little pockets of grace in the midst of chaos” and the use of “conscious restfulness” as a coping strategy.

Dawn-joy Leong, Clement Space in the City.

Hidden away in a cosy corner on the ground floor of Customs House, Clement Space invites visitors to cocoon themselves, to relax and restore balance and clarity. Draped in white tulle, the installation is essentially a cubby house of faux fur cushions, blankets and pom-poms.

A womb-like soundtrack of a faint heartbeat subtly emanates from a James Joyce novel. The recording is actually the heartbeat of Leong’s rescue greyhound who in part inspired the installation with her propensity to curl up and relax in the unlikeliest of locations.

The view from Cloud Heaven

Rush Hour at Cloud Heaven is an animation, audio recording and series of printed works by collaborators Thom and Angelmouse. Thom Roberts, who is autistic, and Angelmouse (Harriet Body), who is not, have been collaborating for four years through Studio A, a social enterprise that supports artists with intellectual disability in their professional art practice.

“Thom and I are always giggling our heads off in the studio,” says Body. “The collaborative process allows us to connect with each other in an art space, where mainstream forms of language-based communication are not paramount.”

Thom gives nicknames to the people, places and objects around him, for example Cloud Heaven for Circular Quay, Christmas Station for Town Hall and Blue Cow for Redfern.

Thom and Angelmouse, Rush Hour at Cloud Heaven.

“I like Customs House (I call it Costumes House) because I can see Cloud Heaven,” says Thom. “I love it there because I get to see all the trains go by and I get to hear the train echo noise. But I don’t like rush hour. I prefer it when it is slow.”

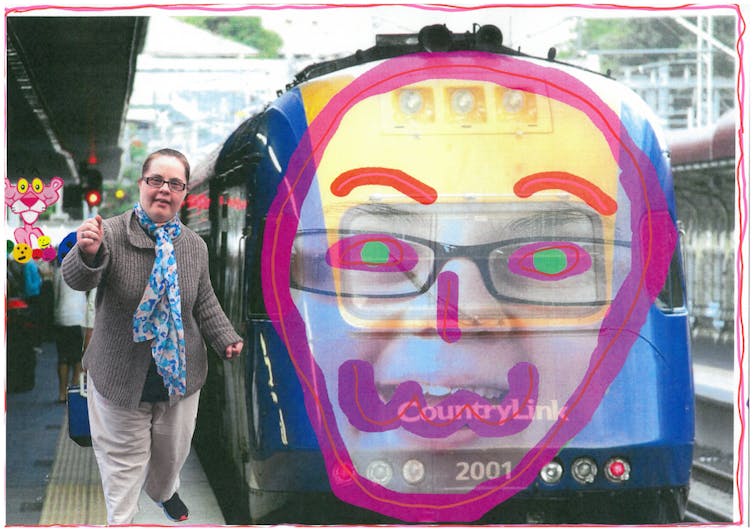

Rush Hour at Cloud Heaven draws on Thom’s enduring relationship with trains, personifying them and incorporating collaged photographs of the artists’ friends and colleagues. As a result, the installation is colourful and often humorous. It is exhibited in a way that is accessible to a diverse audience, with subtitles and audio descriptions incorporated as a creative tool.

“I want the audience to feel happy, sad, mad, thoughtful, surprised, romantic or silly – a whole range of emotions,” says Roberts. “I want all sorts of people to see my work. All people.”

Consultation is key

Another installation that collaborates with autistic artists is the sensory landscape of Snoösphere at UNSW Galleries. It centres on the belief that stimulating the primary senses (under the right, therapeutic conditions) can ease anxiety. Drawing on research about cross-sensory perception, the space is primarily inspired by Dutch spaces used in mental health care and rehabilition, called snoezelen.

Relaxation zone at Snoösphere. Lull Studios

Shoes are left at the door at Snoösphere, while dim lighting, ambient music and tropical bird calls immediately indicate that this is a stress-free zone. It is a playful space where giant pink and purple balloons float over beanbags, and participants are invited to meander through strings of coloured lights, to walk on spongy mats, pebbles and fake grass, to pat vibrating, furry discs that vaguely resemble a science-fiction, birdlike creature.

Lull Studios’ Elena Knox and Lindsay Webb created Snoösphere in consultation with a team of artists. As autism consultant and associate artist, Leong worked with a team of autistic advisers aged ten to 35 years in Sydney and Singapore.

“Consultation is important to any inclusive activity,” says Leong. “It is not only pointless and hypocritical, but also unprofessional, to claim to create something based on a certain paradigm, in this case autism, and not consult the people with lived experience and allow their insights to lead the way.”

Conversely, such consultation can allow artists to create work that resonates with cogency to a wide audience spanning the neurological spectrum. Indeed, Snoösphere and other installations at The Big Anxiety demonstrate just how embracing neurodiversity can engage audiences in a myriad of enlightening ways.

![]() The Big Anxiety continues until November 11 in Sydney.

The Big Anxiety continues until November 11 in Sydney.

Katie Sutherland, Doctor of Creative Arts Candidate, Western Sydney University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.