Jump to:

Imagine this scenario. You are a primary school art teacher with years of experience who is passionate about broadening your students’ horizons with a diverse range of art styles. Your classes are full of art-making activities that allow them to experiment with many different techniques to fuel their own artistic journeys.

But when it comes to teaching them about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander artists’ work, you feel more nervous. You question whether you have sufficient knowledge around the cultural protocols involved in talking to your students about these works. You also worry about things like cultural appropriation, and the last thing you want to do is be inappropriate or disrespectful to the artists, their work and their culture.

This situation is not an uncommon one in classrooms across the country. While teachers are keen to bring Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander art alive for the students in their classrooms, they can also doubt themselves and question their capacities to be able to “teach it right”.

These feelings became clear to the education team at Art Gallery of South Australia (AGSA) when, in January 2018, they offered an art teacher professional development workshop titled ‘Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander art in the classroom’, which attracted 200 educators (after the first workshop sold out, an extra one was scheduled, which also sold out).

Established as part the Gallery’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander art festival Tarnanthi, AGSA’s teacher workshop program has grown to offer a diverse range of educational resources that is maintained throughout the year to assist teachers across the country with their Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander art lessons.

How does AGSA’s model support teachers?

The bespoke program is managed by AGSA’s Education Coordinator Kylie Neagle with assistance from Education Officer Sally Lawrey. Since 2018, this small team has designed a series of frameworks for teachers to demystify what can be seen as complex territory.

As Neagle explains, AGSA’s approach to designing this educational content has been to align it with various Australian Curriculum cross-curriculum priorities (as opposed to targeting specific year level outcomes).

‘This approach means teachers can push and pull the content to suit a variety of year groups and they can use Aboriginal art as their platform to start a conversation with students around a cross-curriculum priority such as sustainability, Aboriginal histories and cultures, or critical thinking,’ she says.

Neagle adds that while these broader curriculum links make the content applicable beyond visual art classrooms, the team is most focused on the needs of visual art teachers and is guided by an overarching “artist first” approach to lesson design.

Read: Tarnanthi 2023 weaves personal stories with skyward visions

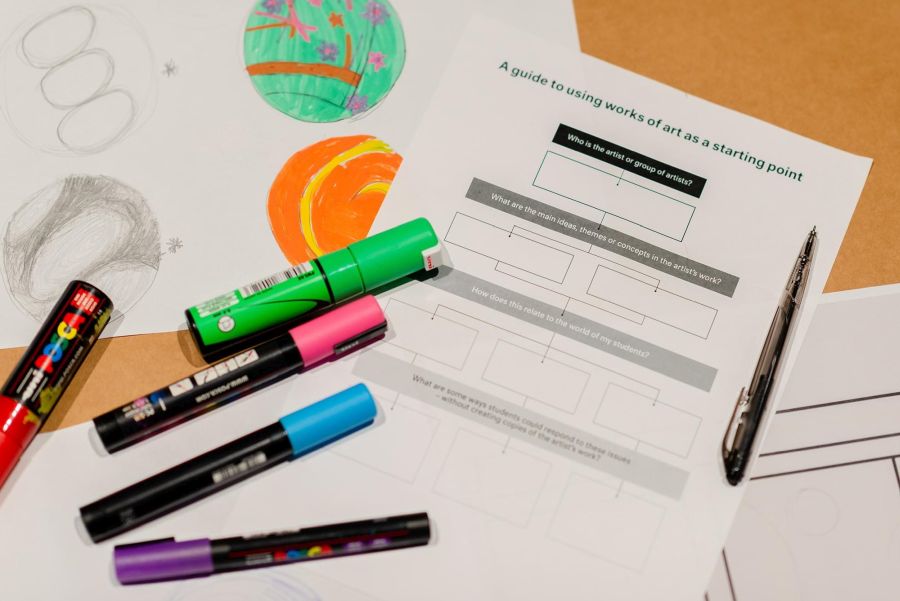

‘One of the most significant components of our resources is the flowcharts we have designed for teachers,’ says Neagle.

‘We have put a lot of thought into designing these as a way to break down an art lesson into basic steps that start with an individual Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander artist’s work, and explore the key themes and ideas within their work from there.

‘In that way, we can avoid any sense that Aboriginal art looks a certain way, or is associated with a particular medium – because that’s not the reality,’ she continues.

‘It’s important to recognise that Aboriginal art is art that is made by an Aboriginal person, full stop. So we need to expose students to that diversity of work and break down stereotypes around what Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander art means.’

Putting it in print: a handbook that’s becoming a must-have go-to

AGSA’s ‘art in the classroom’ program has many tangents – from professional development workshops, to travel support that allows more students to visit the Gallery to see the art in-person. But there is one other, and perhaps more surprising, outcome of the program that is making important impacts.

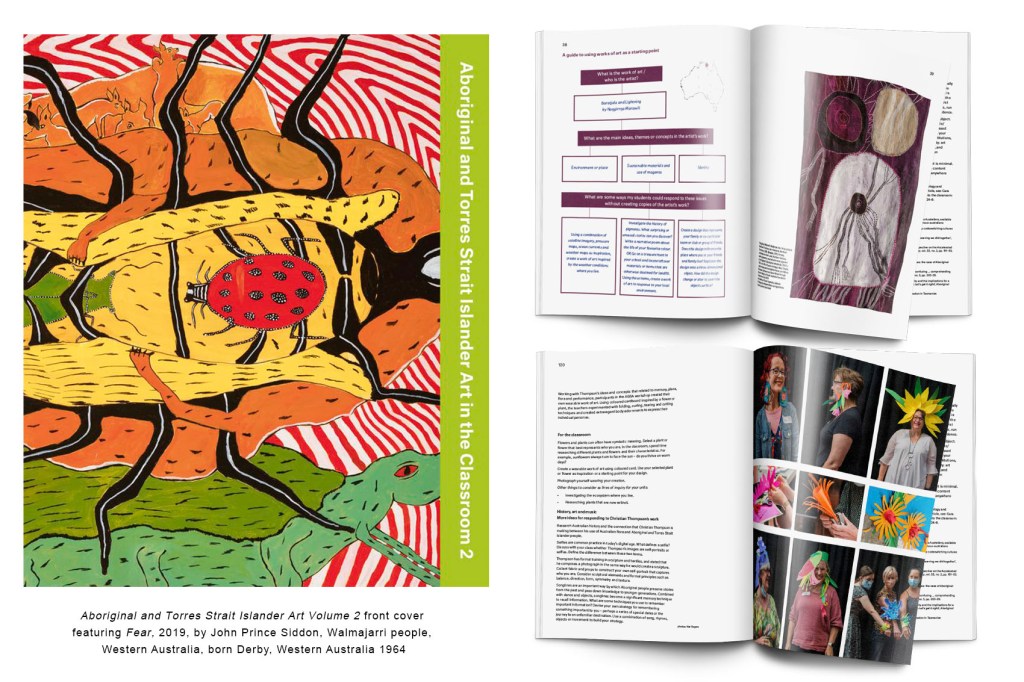

Since 2019, AGSA’s education team have become co-writers and publishers of two hardcopy teachers’ resource books that are fast becoming must-have staples for art classrooms around the country.

AGSA’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art in the Classroom books have been a major investment for the Gallery’s education team in terms of time and money, but the demand has been so strong that the first edition (published in 2019) sold out and was reprinted. All up it has sold 5000 copies.

In response to that demand, AGSA has compiled a follow-up (Volume 2), which it developed in 2022 and which has sold around 780 copies since hitting the shelves in June 2023.

‘The books follow the same logic as our flowcharts in providing simple ways for teachers to approach a lesson that starts with exploring the work of a particular artist, and progresses from there,’ Neagle says.

‘It also takes its cues from a ‘25 facts about Aboriginal art’ framework developed by the University of Virginia’s Kluge-Ruhe Aboriginal Art Collection, produced in collaboration with curators Jilda Andrews, Fenelle Belle, Lauren Maupin and AGSA’s own Curator of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art, Nici Cumpston.’

What do teachers value about these resources?

So, how exactly are art teachers around the country benefiting from these resources?

Katie Driscoll is a primary school visual art teacher from Perth and says she routinely uses AGSA’s flowchart model in her lesson planning, as well as the two books.

‘We’ve used them to explore a wide range of contemporary [Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander] artists to learn their stories, to understand more about the country we live in, and about how the country has influenced the art,’ Driscoll says.

Read: Exhibition review: Vincent Namatjira: Australia in Colour, Art Gallery of South Australia

‘I really believe the flowcharts and the two publications have been a vital development in my teaching,’ she continues. ‘Seeing the results in the children’s work, and their joy with their own creations, and the way they can tell me the stories behind their work, has reinforced the effectiveness of my programs.’

Visual art teacher at St John’s Grammar school (Belair, SA), Kate Wright concurs, saying that she too values the way AGSA’s flowcharts put the artists at the core of students’ learning, and allow them to make broader cross-curricular connections through their study of the art.

‘When students can understand the meaning behind the works it supports authentic learning and promotes greater awareness of worldly issues such as sustainability, historic injustices, social and political views, physicality in the creation of work, social commentary and economics,’ she says.

‘I am finding students are now making those connections between their subjects through the introduction of artists’ techniques and practices.’

Wright has also noticed a shift in the names of “famous artists” that register with her students as important in their daily conversations about art, in another indication of the program’s influence.

‘When I began teaching, students could name Picasso, Monet and Kahlo; now they talk about Kaylene Whiskey, Vincent Namatjira and Naomi Hobson!

‘Introducing Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander artists to students has never been easier,’ she adds. ‘I have definitely broadened my understanding of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander art and have been enlightened by the depth of creative processes that are both historical and contemporary.’