Image credit: Greer Versteeg

In this extract from the latest Platform Paper from Currency House, actor Lex Marinos reveals the artistic skills which have sustained his near half-century career.

* * *

I recalled the beautiful poem, ‘Ithaka’, by Greece’s finest modern poet, Konstantine Kavafy. It’s his advice to Herakles about the labours he faced on his long journey home. It concludes:

Ithaka gave you the marvellous journey.

Without her you wouldn’t have set out.

She has nothing left to give you now.

And if you find her poor, Ithaka won’t have fooled you.

Wise as you will have become, so full of experience,

You’ll have understood by then what these Ithakas mean.

So if acting is my Ithaka, what have I learned from the journey?

For me, the salient point is the primacy of the actor’s role in the creative process. To emphasise this point, Stella Adler would brandish a script as if it were the Ten Commandments, point to the actors and declaim in a stentorian tone that brooked no negotiation, ‘Without YOU this is literature! Without YOU this does not live!’ Most producers, directors, writers and designers understand this and value the actor’s contribution. But for some, actors still remain a necessary evil. Temperamental, untrustworthy, egomaniacal children who should been seen and not heard. Needless to say, this completely blocks the creative process and inevitably leads to an inferior result.

I would like to think I have become a better storyteller, more direct and economical. Less inclined to get in the way of the story. I feel comfortable and relaxed on stage. I have consolidated my process. Basically, it’s Stella Adler with some embellishments and amendments picked up along the way. Let me emphasise that all actors are different, and this is about what I do. I’m not preaching to anyone, or saying this is how it should be done. Through a process of trial and error, this is what works for me, that’s all.

The script is my primary source. The first thing I do is delete all stage directions except essential physical actions. I don’t want the writer telling me how to say something, that’s for me to discover. If the writing is good, the emotion should be inherent in the script. Abstract adverbs like ‘sadly’, ‘happily’, ‘angrily’ are absolutely useless to me. I can’t play a quality, I can only play an action. Did Shakespeare instruct us on how we should deliver ‘To be or not to be’? ‘Sadly’, ‘happily’, ‘angrily’? The American actor Christopher Walken deletes all punctuation also from his scripts, leaving only the words. And I think it shows. It’s what I like about his performances: they are unpredictable, idiosyncratic, oddly punctuated.

So I read the script and react to it. First impressions of story, possible themes, characters, dialogue, style. Using my favourite script pencil, I circle unfamiliar words, names and places. I populate the margins with question marks. ‘I wonder what that means?’

Then I start my research. This is the essential foundation I need before I can attempt to tell the story. Research is my security blanket. Since my student days, I’ve always loved it and its importance was emphasised by Ms Adler. I look at the ‘given circumstances’ in the script. The time and place, the people, the events. I look at my character. What do we know about him? His age, occupation, relationship to the other characters. What does he say and do? What do others say about him and do to him?

Then I break the script down into scenes and further down to beats, small pieces of action. My questions become more speculative. Why does he say that? And do that? What does he want? How does he want to affect the other character? What is his action? At the same time I research the play and the writer, the period and place that contextualise the play. I read about the social, political, and artistic movements of the time. I look at paintings and photos for some visual clues to period and character. What music would he have listened to?

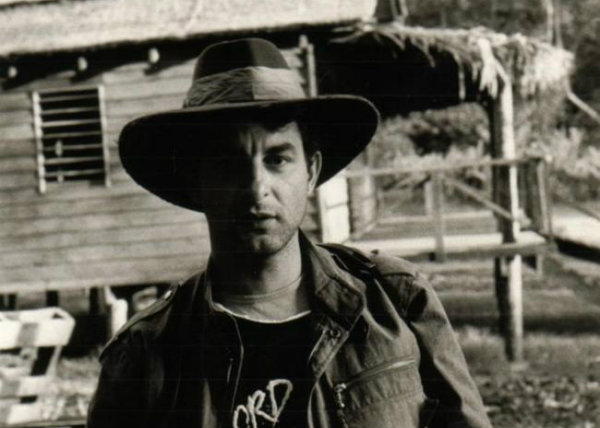

Lex Marinos in 1984, on the set of the feature film, An Indecent Obsession.

I try to achieve all this before rehearsals start. I want to concentrate on the script and allow my imagination free rein, supported by the research. Working with the director and the other actors on the journey of discovery and execution is the most exciting part of the process for me. Experimenting with different choices and actions, being receptive to what the others bring, constructing the performance, finding the rhythms, allowing the story to unfold. I seek out the new information in any scene, feeling how it advances the story. I try to experience things for the first time.

This is where grandchildren are very helpful. When I babysit I can observe their simple pleasures and hurts. Running around in the rain, on the swings, patting the dog. The purity of their response is valuable material for an actor. If only I could bottle their innocence. The English director, Jonathan Miller, once said that a big part of his job involved getting actors to forget things they should never remember, and remember things they should never forget. I try not to repeat things I have done before, it’s such a lazy shortcut. I like to keep my options open as late as possible to allow for the needs of the other actors. Once a scene is working to everyone’s satisfaction, I’m happy to place it on the back of the stove on a low simmer, and wait for an audience.

Once the show is on, it tends to dominate my day. Everything is timed around the curtain rising at eight o’clock. I usually have a late lunch and a light snack before the show. I don’t like performing on a full stomach. I might try and have a short nap in the afternoon. I drink plenty of fluids, non-alcoholic. I check that my voice is working. I like to arrive about an hour before the curtain. Normally I don’t drink coffee in the evening, but if I’m doing a show I will have one for that little caffeine hit. Once I enter the theatre, I switch off my phone and leave the events of the day behind. I start to focus on the show. I check my props and costumes, walk around the stage muttering lines to myself. I do a light vocal and physical warm-up. Once I’m satisfied everything is working I don’t overdo it. I conserve energy for the show. In the dressing room there is usually some light banter, a bit of gossip maybe. Everyone is different in the way they prepare. I gradually withdraw into myself and just focus on what I need to do. I always have the script with me and like to glance at it, trying to see the words for the first time.

I’m confident enough now to allow the show to happen. I’ll play my actions but the lines will be delivered differently each time. They will be an expression of how I’m feeling at that moment. Each audience is individual and so, therefore, is each show. The basic architecture will remain the same, but the interior decorating will change. Back in the dressing room, I don’t analyse the scene that’s just gone. That can wait until after the show. I can’t change what’s happened. I need to concentrate on the next scene, change costume, have a drink, recalibrate for what is to come.

Marinos, right, with fellow Kingswood Country castmates: Ross Higgins and Judi Farr (front) and Peter Fisher and Laurel McGowan (back).

When the show’s over, we usually have a chat and a couple of laughs about the performance. Unless I’m meeting friends, I then toddle off home. If it’s an emotionally taxing show, which forces me into uncomfortable mental spaces, I take Daisy for a late night walk. I have a smoke, watch television, read, sleep, and with luck I wake up again next morning. Then I start preparing for that night’s performance. And so it goes, very enjoyable factory work.

It is somewhat different in film and television, although the basics remain the same. Kingswood Country was really weekly rep with the same characters. The script would arrive at the start of the week, we’d rehearse for the next few days before going to the studio. There we would rehearse with the cameras and then play in front of a live audience. After that I would have a meal and a nap before repeating the performance for a second audience. This minimised the amount of stoppages and retakes, and enabled the producers to edit between the two recordings, choosing the best scenes from each. Inevitably the first show felt like a dress rehearsal and the second show tended to provide the bulk of the final edit. Multicam studio drama is more or less the same but without an audience.

Film and miniseries are different again, and present particular acting challenges. Whereas theatre is linear and continuous, allowing the actor a logical emotional journey, film is fragmented. Murphy’s Law dictates that your big scenes, often late in the narrative, will be scheduled before your establishing scenes, and these will be shot last. The actor has to be very clear about the story and where he is emotionally at any given point. Preparation is paramount.

The Slap

I had been a big fan of Christos Tsiolkas’ writing since his debut novel, Loaded, and as soon as I read The Slap, and heard that it was to be adapted into a mini-series, I knew I wanted to be in it. Only problem was I wasn’t sure whom I could play. I was too old for the main male characters, Hector and Harry, and seemingly too young for the father, Manolis. Nevertheless I was thrilled to get an audition. I practised my Greek and applied what I hoped was a subtle amount of makeup to seem a bit older. The audition went well and I received a call back. Again it went well, and now it was a matter of whether I could look old enough. Personally, I didn’t think it was that big a stretch, but I was hardly objective. We consulted with the makeup supervisor and she confirmed that she didn’t think it would be too big a problem, and so I had the green light. Next obstacle concerned my health. With a dicky ticker and leukaemia I couldn’t pass the medical without indemnifying the insurers and providing guarantees from my doctors that my pre-existing conditions would not hamper my ability to work. Eventually all the hurdles were jumped, negotiations concluded and contracts signed.

I cleared all other commitments, corporate gigs, radio and teaching, so I could concentrate on the task ahead. The truth was that the leukaemia was becoming fairly enervating and I wanted to conserve as much energy as I could for what I knew would be a gruelling shoot.

I began my preparation by re-reading the novel, gathering all the information about Manolis in order to build his back story. I began my wider research using the massive archive about Greek Australians that my friends, photographer Effy Alexakis and historian Leonard Janiszewski, had accumulated. I listened tearfully to some interviews Leonard have done with Dad. I talked to Christos’ father and tried to capture some of his vocal mannerisms. I looked at photos and listened to Greek music from the period. Until I felt I knew Manolis. I had grown up with men like him, and witnessed the struggles they had endured to raise families, working dirty, punishing jobs, seeking comfort and solace among their compatriots, trying to fit in, trying to educate their kids.

Lex Marinos as Manolis in The Slap. Image via www.abc.net.au

The story was told over eight episodes, of which one (episode six) was driven by Manolis. I extracted all his scenes from the scripts and put them together, discarding everything else so that I was just working with his story. This became my ‘bible’. I wanted to remain ignorant of anything that didn’t involve him. I deleted all of the scripted suggestions and worked just with his dialogue and what he did. Then I started plotting his emotional journey, his actions and discoveries, breaking them down into ‘beats’.

I worked with a dialogue coach, Kosta Nikas, to try and make my Greek sound native-born rather than inflected with my Australian accent. I translated my English dialogue into Greek and learned it that way, forcing myself to think Greek and translate back into English before speaking. Externally, I let my facial hair go untrimmed, allowing it to sprout from my ears and nostrils, eyebrows running wild. I put on some kilos (without much effort), stopped taking anti-inflammatory medication, allowing the stabs of osteoarthritis to remind me of my physical (and spiritual) deterioration. To produce Manolis’s limp I used an old acting trick of putting a pebble in my shoe.

Crucially for me, I used objects belonging to my father: his komboloi (worry beads), Hellenic Club membership badge, key ring. I wanted that connection to Dad and his generation of migrants. Indeed, that connection was reinforced during the make-up process as the ageing prosthetics were applied. I began to anticipate the moment where I could look in the mirror and no longer see myself, but my father. Even now, when I see an image for The Slap, I still think I’m looking at Dad.

Platform Paper 53, The Jobbing Actor: Rules of Engagement by Lex Marinos, is now available from Currency House. Visit currencyhouse.org.au for details.

The Jobbing Actor will be launched in Melbourne on Thursday 2 November, at an event hosted by Theatre Network Australia and featuring Marinos in conversation with playwright Hannie Rayson. Click here for booking details.