I feel compelled to start this review by apologising to the Art Gallery of Western Australia (AGWA). Not the administrators, curators, or even the artists behind the hundreds of exhibitions I’ve attended – no, my remorse extends to the building, the demure hexagonal structure that’s entertained and educated visitors for 40 years. While I’ve long admired the twisting central staircase and pondered the honeycomb ceiling, I’ve largely ignored, and sometimes sneered at, the building design. Having just left the Perth Brutal: Dreaming in Concrete exhibition, I’m left with a newfound appreciation, pride, and dare I say, love for the building.

With much buzz about the museum upgrade around the corner, it’s timely to reflect on how this internationally acclaimed gallery came to be. Opened in 1979, this year marks the 40th anniversary of AGWA’s construction. Its birth was the result of a decade long push to relocate art works from the damp, un-airconditioned dungeon of the old gaol.

To celebrate, the gallery is holding a season of special exhibitions and events collectively named AGWA 40, of which Perth Brutal is the star.

Laid out in sequential order, Perth Brutal takes viewers from construction to completion through plans, design models, and early promotional brochures. The wide range of plans shown highlights the different visions for the building. Also included are images from one of Australia’s pre-eminent architectural photographers, Fritz Kos.

Robert Cook, AGWA Curator of 20th Century Arts, said, ‘Kos wasn’t just documenting the construction, he had a distinct aesthetic and a dramatic perspective on things, so his images helped bring the building alive as an entity and as a sculpture.’

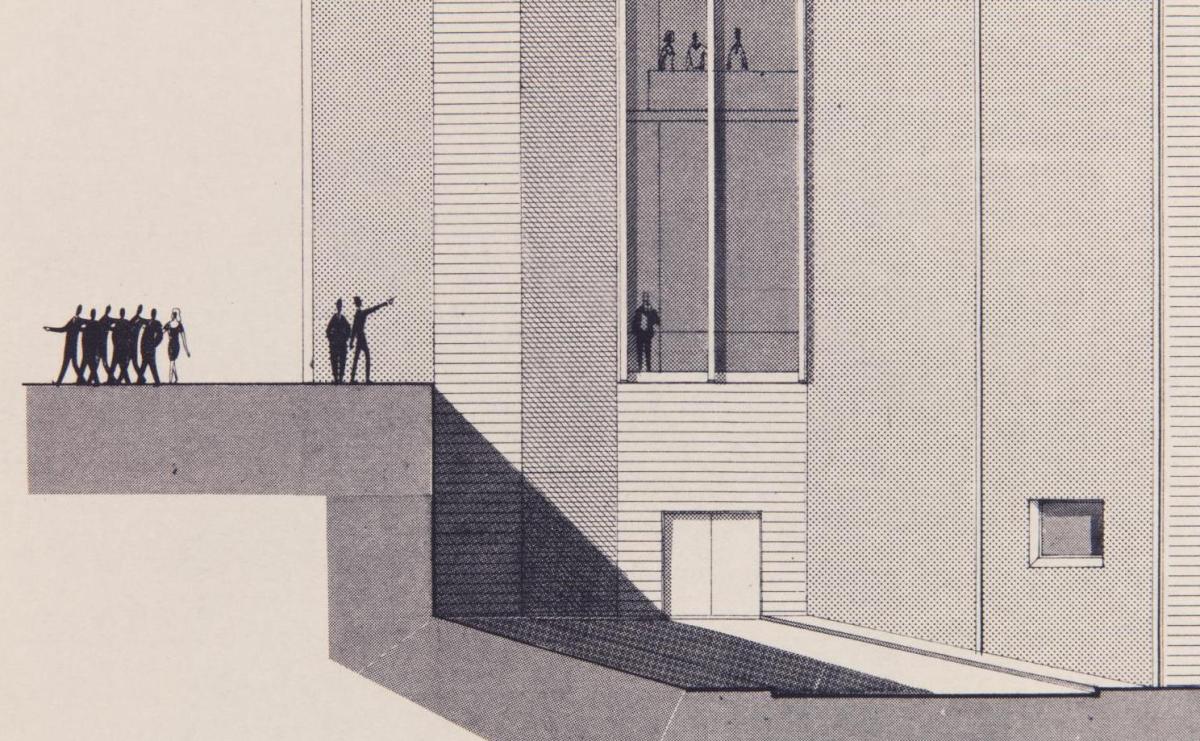

Art Gallery of Western Australia in 1979. Image: Fritz Kos, sourced from the State Library of Western Australia.

Six things stood out for me:

Persistence

It was fascinating to view earlier plans that had the gallery located in the Government House gardens. Equally interesting was the reminder of the many years spent arguing about sinking the Northbridge rail line, something we take for granted today. Tired of waiting for a decision to be made about the rail line, and with a strong desire to ensure the gallery was linked to the city, the designers surged ahead, solving the problem by including a walkway over the tracks. One design suggested the gallery would include a pedestrian walk through with art displayed on either side, effectively creating a 24-hour exhibition space. What a shame this iteration got lost along the way.

Quotes

Dotted throughout the exhibition is a handful of quotes, one of which outlines the mindset behind the raw, undecorated concrete appearance of the building, a design style known as Brutalism.

‘Be very careful in accepting design suggestions. The main purpose of our work is to create a suitable environment for enticing visitors to the works of art. It is not the purpose of the building to compete with works which it shelters. Many examples from overseas prove the point that monuments for directors or architects are not necessarily the good galleries,’ said Tadeusz Andrzejaczek, Executive Architect, P.W.D, Perth WA.

Image: The Art Gallery of Western Australia Opening Brochure, 1979.

Hexagonal plan

The brainchild of Polish designer Charles Sierakowski is the gallery’s hexagonal plan. As a result, visitors can be in one space and spy something intriguing in another. That explains why I’ve often found myself wandering into an adjoining exhibition that I wouldn’t have purposely gone to.

Melissa Harpley, curator of 19th-century art at AGWA, said, ‘The radical new layout, with no 90-degree angles in the exhibition spaces, continues to provide a wonderful canvas for curators to work with. The emphasis really is about transforming the viewing experience and the flow of movement through interconnected gallery spaces.’

Natural light

Another clever feature is the amount of natural light reaching the core of the building. On my most recent visit the afternoon sun was streaming into a rest area, meanwhile an adjacent exhibition space was suitably dark and moody. The natural light kept me contacted with the outside world, and minimised that stuffy, claustrophobic feeling you sometimes experience.

Honeycomb ceiling

Then there’s the honeycomb ceiling. While it looks like it’s made of heavy concrete, it’s actually hollow and used to hide the inner workings of the gallery – very clever.

Board composition

Lastly, it was a surprise and delight to see artist and then board chair Ella Fry, front and centre, who mentioned the ‘immeasurable joy’ in seeing construction start.

Image: New Art Gallery of Western Australia Structural Engineering Brochure, 1979. Public Works Department of WA.

Thanks to the exhibition I no longer consider the building ‘brutal’ nor ‘bunkerish’. I now enjoy the subtle finesse of this humble structure. I hope you get to see this enlightening exhibition. There will be guided tours, talks, performances, a symposium with Curtin University’s School of Design and the Built Environment, plus a book called A Brutalist Galllery In Perth.

4 stars out of 5 ★★★★

Perth Brutal: Dreaming in Concrete

21 September 2019 – 17 February 2020

AGWA

Free admission

Open Night on 1 November includes Co:3 dance company performance and an appearance by design guru Tim Ross.