There’s a strange absence at the heart of the National Gallery of Victoria’s summer blockbuster: Keith Haring, Jean-Michel Basquiat: Crossing Lines, and it’s not just the ghosts of these two vibrant artists who died tragically young. It’s the ghost of Haring’s sexuality, which although an abiding theme of his work seems to have been deliberately excised.

Keith Haring shot to fame when he started to fill blank, black-papered, ad spaces in the New York underground with his chalk line drawings. He completed over 5,000 of these over a five-year period in the early 1980s.

One of the fascinating pieces in the NGV’s sprawling tribute to Haring and his friend Basquiat, is a short video of Haring at work in the subway.

The speed at which this elfin figure darts around, completing each image in an astonishing single gesture, tells us something about the way Haring put his body into his art. As one critic put it: “He danced his drawings, perceiving the act as a performance and a shamanistic tribal ritual of everyday life.”

This shamanistic energy was directly linked to Haring’s sense of himself as a gay man. He told his biographer the flow of his drawings was connected to his sense of sexuality and this sexual/artistic flow was about establishing a “universal connection”.

“Sexual energy may be the single strongest impulse I feel – more than art,” he wrote in his journals.

Yet the words “sexuality” or “gay” don’t appear anywhere in the wall notes for this show. There is one passing reference to his homosexuality: describing a house where one of the works was created, the wall card notes that Haring lived there with his boyfriend Jean Dubose and others.

But the dance around Haring’s sexuality is even more troubling when we contrast the public notes accompanying the show with the exhibition catalogue. The blurb on the catalogue says both artists “employed signs, symbols and words to explore ideas around race, sexuality, spirituality and other aspects of contemporary life”.

The introductory wall note in the gallery tells a similar story but omits the reference to sexuality: “Haring and Basquiat were humanists. Indifference was not their style. Each artist’s work speaks of struggles against exploitation, consumer society, repression, racism and genocide.” Why this difference in emphasis?

In the audio tour highlighting how the glittery sheen of Haring and Basquiat’s celebrity often obscured the true significance of their work, Jenny Holzer, an artistic contemporary, comments:

At times it seemed the fluff took over. Which was unfortunate, because the important political and cultural content, the societal references that were in both men’s work, were neglected in the party and money frenzy. You’d have to be dim to miss the gay pride and liberation message in Keith’s work, and that Jean-Michel was a race man, but people didn’t always talk about that.

While the NGV show attends to the theme of race it neglects the theme of gay pride in Haring’s work, seeming to commit the very mistake Holzer warns against.

It is puzzling that none of Haring’s many sexually explicit and gay-themed works have been included in this show: a particularly odd choice when Haring’s groundbreaking gay and HIV themed work would have played well into the exhibtion’s overarching narrative of political involvement. Was this a misguided attempt to make it more “family friendly”? (Many of the images are accompanied by “For kids” wall panels.)

Writing in Vanity Fair in 1997, art critic and former editor of Warhol’s Interview magazine, Ingrid Sischy warned staff at New York’s Whitney gallery not to fall into this trap as they prepared one of the first large Haring retrospectives. It’s sad I am writing this article with a similar message over 20 years later.

“[Haring’s] work … came after a long period of puritanism in art, and his images of the body, sex, and homosexuality were part of the taboo-busting that was as intrinsic to this period as the Reagan rightwingers,” Sischy writes.

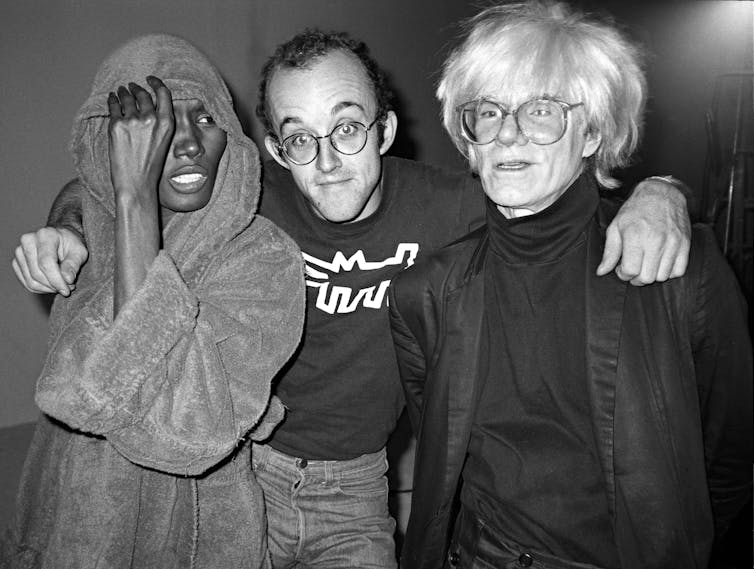

The NGV exhibition celebrates both Basquiat and Haring’s connection to Andy Warhol and the lineage and influence is obvious. But Sischy notes that in one respect Haring “went beyond his idol”. Shes continues:

Because of the tenor of the times, Haring’s queer sexuality was much more out-front than Warhol’s enigmatic image, behavior, and sensibility … Haring’s open homosexuality cost him with critics who just couldn’t go there and who didn’t see sex as art, politics, a language all its own for a generation absorbed in exploring it.

His response to HIV

What is perhaps most shocking about the NGV show is the complete absence of images representing Haring’s response to HIV. The epidemic is mentioned as one of his political concerns but not depicted except abstractly in the extraordinary late apocalyptic piece Walking in the Rain.

Haring’s Ignorance = Fear Silence = Death was an iconic artistic intervention of the early AIDS epidemic and his widely distributed safe sex images were used in education campaigns that arguably saved lives. Haring set up the Keith Haring Foundation to help continue this HIV education work after his death.

In an interview with Rolling Stone published six months before he died, where he spoke about the importance of his HIV education work, Haring also spoke openly about being HIV positive and facing the end of his “story”.

When asked by the interviewer whether he thought all gay men should be open about their homosexuality he replied that people should be “normal about it”.

In summing up Haring’s distinctiveness historian Michael Murphy writes: “Haring unashamedly and unselfconsciously dared to express homosexual sex as SEX not subtext, oblique references or innuendo.”

For Haring sex and sexuality were a normal part of life and that is why it proliferates as a theme throughout his work from his earliest art school paintings to his extraordinary mural for the NYC LGBTI Centre, completed in the last year of his life to celebrate the 20th anniversary of Stonewall.

To reduce Basquiat to a black artist or Haring to a gay artist would be a simplistic misreading, ignoring the wonderful complexity of their work.

But if this exhibition had failed to recognise the importance to Basquiat’s work of his experience of being a young, black man, in the same way it has ignored Haring’s gayness, it would have been condemned.

By ignoring Haring’s sexuality the exhibition also misses a central narrative of the crossing lines in the parallel journeys of these two artistic pioneers. They each found a powerful vernacular language for their sense of identity and sense of difference. This is what makes them so relevant and so powerful today.![]()

Marcus O’Donnell, Associate Professor, Pro Vice-Chancellor, Teaching and Learning, Deakin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.