Over the past few months, most of us have found ourselves in unfamiliar territory trying to shape the formlessness of our days while contending with physical separation.

Many incarcerated people, however, have spent years figuring out what to do with their time in isolation. Some discover faith, while others read and educate themselves. Then there are those who become artists.

For the past 25 years, I’ve worked as senior curator and co-founder of the Annual Exhibitions of Art by Michigan Prisoners at the University of Michigan. Each year these exhibitions draw thousands of people who view and buy the work. For the artists, these shows are a source of validation and support. They get to keep the money from sales.

Getting to know many of these artists confirmed my belief that art making is a basic human activity that gives shape to meaning. In conditions of extreme confinement, finding meaning becomes all the more urgent.

Most prison artists don’t consider making art until they become incarcerated. For many, it is a choice of growth over deterioration.

For others, like Wynn Satterlee, a former inmate in a maximum-security prison, it was a matter of life or death.

In prison, he was told he would die of cancer. With the help of friends, he took up painting.

“I painted to escape the suffering and the pain,” he told me after he was released from prison. “Ten hours a day, seven days a week, for over seven years. And I overcame cancer.”

Oliger Merko, who was born in Albania, is serving a life sentence with the possibility of parole.

“It really shakes you up to get that sentence,” he told me during an interview at Ionia Maximum Facility in Michigan. “I was totally hopeless, drifting, with no direction. I started thinking more deeply, and when I discovered art, everything opened up. Now I paint for three or four hours a day and don’t want to stop, even if it’s chow time. It’s a real second life more than an escape.”

To make this kind of leap into artistic expression requires some basic human capacities that we often ignore but can be summoned under extreme circumstances. One involves finding the extraordinary in the ordinary – a requirement for many prison artists, who lack money for expensive art supplies.

Some eventually learn that almost anything that can be picked up and held can be made into a beautiful three-dimensional art object. They use toilet paper and glue, soap, cardboard, paper, stones from the yard, plastic lids and bottles. Robert Sarber’s sculpture “Buck/Deer” was made from toilet paper and glue and then painted with acrylic.

Kenneth Mariner makes dioramas out of cardboard, old folders, thread, glue, tissue, acrylic paint and twist ties.

Many prison artists cultivate the ability to focus for extended periods of time. This discipline is a way to resist the monotony and violence of prison life.

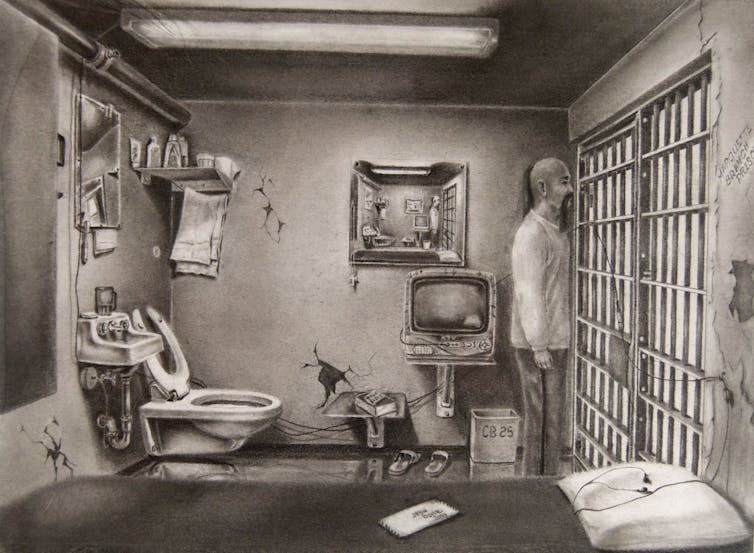

John Bone learned to draw by doing hundreds of drawings of his cell, sometimes working 16 hours a day, observing every detail of his environment. His scrutiny of something with no intrinsic beauty – coupled with close attention to the tonal values and spatial structures of his drawing – resulted in remarkable works.

While learning to draw, Billy Brown was getting frustrated. Then, one day, he prayed for a vision and came up with an extraordinary technique for colored pencil drawings on black paper. At the beginning of each stroke, he lightly presses on the paper; as he moves the pencil, he increases the pressure, which makes the color more saturated.

What enables a person to focus with such attention for so long in such isolation?

The prison artists I know are motivated by a powerful need to assert their identity and explore unmet needs for love, beauty, nature and animals, a sense of accomplishment, and the ability to communicate intense feelings. This desire is so strong that people start making art without the self-doubt that most non-artists in the world would feel.

Karmyn Valentine, a carpenter by trade, had never made art before coming to prison. In her first painting, “My Pain,” she was able to find form for her suffering.

“I was abused and betrayed and so that is why the arrow is coming from the back,” she said. “I am touching the arrow because the pain is my constant companion. I lived with it before I came into prison and I live with it now.”

There’s a freedom these artists can access in the choices they make about content, materials, marks, texture, colors, shapes and surfaces. The very act of making these choices is a way to reclaim their agency. This is significant in a system that treats people as objects to be moved about, counted, chained, searched and assigned a number.

Time and the future change when prisoners become creators rather than objects. Once artists imbue their day-to-day lives with purpose and meaning, waking up no longer becomes something to dread. As Merko explained: “Before I became an artist, every day was routine, and now, even though in prison you want the days to pass quickly, I sometimes wish the day was longer when I’m painting. It’s like I don’t belong in time anymore.”

Prison artists develop a practice in which one work of art leads to another, pointing them toward a path of endlessly unfolding possibilities and a feeling of being grounded. To those of us living with stress and frustration during COVID-19 restrictions, these artists demonstrate how to develop an inner space of freedom – and how to live imaginatively and purposefully in a strange new world.

![]()

Janie Paul, Professor Emerita of Art and Design, University of Michigan

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.