ArtsHub was recently on the ground at Uluṟu (NT) for the launch of a new cultural tourism offering Sunrise Journeys. The launch coincided with 40th anniversary of the Ayres Rock Resort (today operated by Voyages Indigenous Tourism Australia*), the company that is behind many of the cultural offerings at Yulara and Uluṟu.

The trip was back-to-back with a stay at Hadley’s Orient Hotel in Hobart (which was celebrating its 190th anniversary), and a mandatory visit to the cultural tourism superstar, Mona – David Walsh’s Museum of Old and New Art.

In tandem, these venues got us thinking. Clearly, cultural tourism has changed dramatically (it was barely an idea forty years ago, let alone 190!). But more so, it triggered us to question what is driving cultural tourism today, especially in a post-Covid environment that is hyper alert to cultural respect and acknowledgment, that is entertainment driven, and where economic return is part of a funding dance.

In this story:

The big shifts

While the origins of cultural tourism could be argued existed as early as the 1950s, as planes trundled alongside the sacred face of Uluṟu up until 1984, and people clambered their way to the top of “the rock” until October 2019, today the “I was here” mantra has been replaced with a new respect-driven desire to connect.

For Uluṟu, that shift started with the development of the service town Yulara, which became fully operational in 1984. Today the town has a population of 835 people, most of whom work in some capacity in the tourism sector.

Matt Cameron-Smith, CEO of Voyages Indigenous Tourism Australia, explained, ‘Cultural tourism is an interesting space to be in, because it is about how you create a connection – how you bring culture forward.’

In an earlier interview, he told ArtsHub, ‘It is a bit like greenwashing, if you do it the wrong way. You have got to do it in a meaningful way. For us it starts with employment and empowerment.’ Voyages employed just five Indigenous workers in 2011, which prior to Covid had grown to 300. ‘Now, one in three of our team members are Indigenous,’ he said. ‘It is about using tourism as an enabler.’

‘It means that cultural tourism isn’t just the show (you see). It is about your chef, it’s about your waiter, your front office manager, and it’s about a sharing of culture, and Aṉangu are incredibly generous in terms of welcoming tourists,’ he said.

Keeping cultural tourism genuine

When asked what cultural tourism means on the ground, Cameron-Smith said that tourists today have ‘a pretty good bullshit detector as travellers; you can smell it if it’s not authentic.’

Remember when the self-led travel network Air BnB introduced ‘experiences’? It took the idea of cultural tourism out of the hands of tour operators and connected it genuinely at a groundroots level, busting open the silos of elitism and economics. This has especially been a win for the arts and cultural sector, and has forced a rethinking.

It is about that magic exchange between the visitor and the visited, when you go somewhere that has a cultural purpose.

Matthew Cameron-Smith

Read: Cultural Tourism that breaks down elitism

Another great example of keeping it genuine is Hadley’s Orient Hotel in Hobart. They have employed a full time Director of Art and Cultural Experiences, Amy Jackett, who has created a QR-trail around the hotel sharing stories and histories, as well as a bespoke game cards for guests and a murder mystery game drawing out history in a fun and innovative way.

Dean White, General Manager of the Hotel, explained: ‘It’s really interesting to me, to see how the cultural tourism offering has changed, especially in the post-Covid climate. Without the art work and the stories, it’s a bit of an empty shell.’

He continued, ‘People’s wants, I feel, have shifted. Experiential tourism is, and has been, an important part of the industry for a while, and our ambition to restore habits is a really important part of what we consider cultural tourism.’

‘We’re trying to bring back an experience which is not a mainstream hospitality experience, but one where people will want to learn and participate,’ said White. He added that while less people are travelling post-Covid, ‘those who have been, are keen to experience things in a more connected way.’

‘What Amy’s doing, is to keep people engaged and interested all year round, and that’s really important – not just for festivals or our prize – and it’s less about, you know, hotel chic.’

Tourism with a First Nations lens

It proves that people are willing to curate their travel experiences around arts and culture. Now, on top of Segway tours and camel tours in the Central Desert, people can sit down for a free chat and learn about traditional spears, bush-tucker and landcare, storytelling by artists, sky dreamings and traditional astrology. It is a more holistic approach.

Read: Surprises as most cultural Australian cities (per capita) revealed

Capitalising on this trend, NT Tourism have been active in parceling up cultural offerings. Last May (2023), they launched the Red Centre Light Trail, a multi-sensory destination-driven offering, not unlike the drive-yourself Free Range Art Highway through the Nevada desert, the extremely successful Silo Art Trail in Victoria.

What this demonstrates is that cultural marketers are recognising that beach, forests and malls alone are no longer delivering what people want.

The Red Centre Light Trail connects Alice Springs – where the light festival Parrtjima is presented annually – with the all year-round offering at Kings Canyon, Light-Towers, 69 colourful towers that respond to music created by Bruce Munro, to Munro’s Field of Lights at Uluṟu, as well as the drone show Wintjiri Wiru, and Sunrise Journeys. Cultural storytelling and immersive are what define these offerings.

Cameron-Smith explains, ‘It’s just a way to amplify culture, and share culture in a different kind of way – and it makes it more accessible to a degree. For many people, they want to know more, but they don’t know how to get it. So this is a way of making it more accessible.’

Impact, politicians and dollars

In recent weeks, the Australian Museum (AM), the National Museum of Australia, and the Biennale of Sydney have each released attendance figures for blockbuster events this year, focusing on numbers and dollars. This is largely a function of putting arts and culture in to tourism and political vernacular.

We all know in the arts, that the impact of culture runs far deeper, and beyond any short-term, quantitative outcome. However, to blur the silos of the sectors, such language is here to stay until we find better ways of “selling” culture to the suit-wearers.

The positive news is that the numbers show cultural experiences continue to be on the rise in demand.

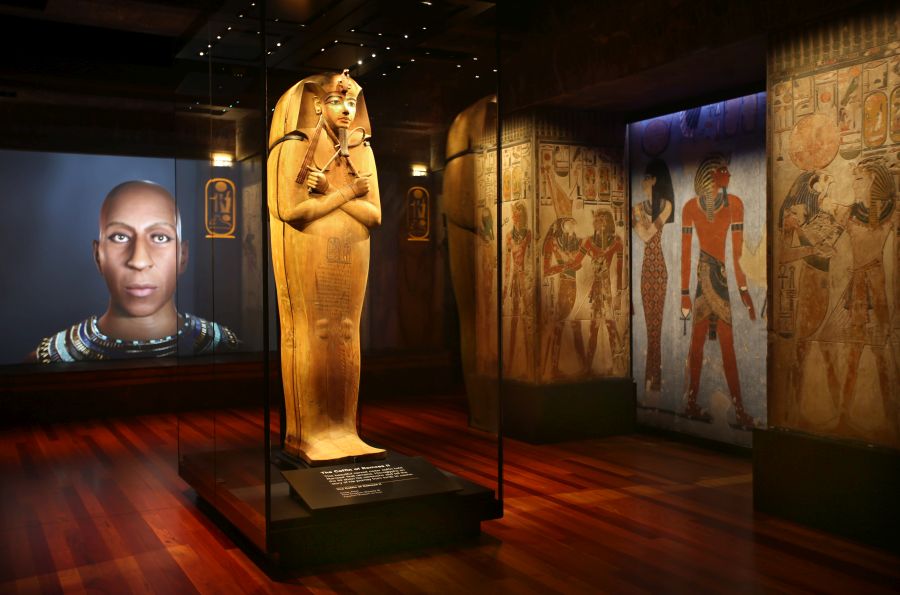

Ramses and the Gold of the Pharaohs at the Australian Museum, was described ‘among the most successful museum exhibitions in NSW history, both in terms of visitors and economic impact,’ confirming 508,000 visitors (60,000 interstate and 10,000 international) saw the exhibition and contributed more than $57 million to the NSW economy.

Similarly, the National Museum of Australia’s Egyptian blockbuster Discovering Ancient Egypt ‘has smashed records for all past shows (with 208,000 attending) … making it the biggest blockbuster in the Museum’s 23-year history,’ and the 24th Biennale of Sydney also reported a record-breaking three-month run that attracted over 771,000 visitors.

How predictions are playing a role in touting cultural tourism

There has been a recent trend, which I have observed coming out of Covid with the promotion of major events, that is a kind of crystal ball marketing. A great example is the statement by Ron Tan, Executive Chairman & Group CEO, NEON Group, which partnered with the AM to bring the Ramses exhibition to Sydney. He was quoted in the Museum’s statement on the exhibition’s success: ‘If we had not been successful in securing the Ramses exhibition for Sydney, and it had been hosted elsewhere in Australia, an estimated outflow of more than $6 million would have occurred from NSW visitors travelling out of the state.’

Who is this lightening bolt moment intended for? In a similar way, major arts events are being parceled up with economic predictions, to sell their benefit ahead of time. With the recent announcement of the artists in this year’s Asia Pacific Triennale (APT) at the Queensland Art Gallery / Gallerlly of Modern Art (QAGOMA, 30 November to 27 April 2025), Minister for the Arts Leeanne Enoch reminded that the APT has generated almost $14 million for the local economy, adding that ‘QAGOMA plays an important role in growing cultural tourism and building artists’ and artsworkers’ careers ahead of Brisbane 2032, when the eyes of the world will be on Queensland’s exceptional arts and culture.’

Read: What the APT11 artist list says about now

It was the same with the announcement of the forthcoming Dale Chihuly exhibition in the Adelaide Botanic Gardens (27 September 2024 – 29 April 2025). Journalists were briefed on the exhibition’s success in the Phoenix Desert Botanic Garden (2021), which led to a 100% increase in visitation, adding that Phoenix also saw an increase in audience diversity, and over 31% of visitors were from outside the Phoenix area and 11% were international visitors, stating 22% said Chihuly was the primary reason for their visit, and over 32% visited with children.

Read: Chihuly to transform Adelaide Botanic Garden with epic glass installation

Like a trail of bread crumbs, journalists were also told that Adelaide Botanic Garden sees over 1.3 million visitors per year, with South Australian Minister for Tourism, Zoe Bettison adding, ‘What’s more, its lifespan across spring, summer, and autumn, alongside some of our longest-running tourism drawcards in the Adelaide Fringe and Adelaide Festival, lends itself to multiple visits.’

Much has been said about Cultural Tourism – let’s face it, it’s not a new term, and it’s a ‘whitefella’ one at that. But there is an underlying factor that remains in bed with all offerings – it is a billion-dollar industry – and it is in flux.

It is a dangerous territory of hype and expectation, where arts and culture sit under the latest buzz word of the “visitor economy.” Getting the balance right is key, to ensure these offerings are presented to potential audiences as genuine.

Why arts and tourism need to value each other

For me, these numbers speak more about a tourism sector need, than an arts sector needing to prove itself.

If we are to take the helicopter higher on all this thinking, it would be an observation that there is a huge opportunities for the arts and culture sector – and it is growing – but it comes with a warning to not sell ourselves short.

Yes, be prepared to adjust to the machinations of the tourism sector and fall into their stride, but like any partnership negotiation at the board table of any arts organisation, remain true and remain genuine to grow in this space.

* Voyages Indigenous Tourism Australia is a wholly-owned subsidiary of the Indigenous Land and Sea Corporation (ILSC) and manages tourism and resorts on its behalf.