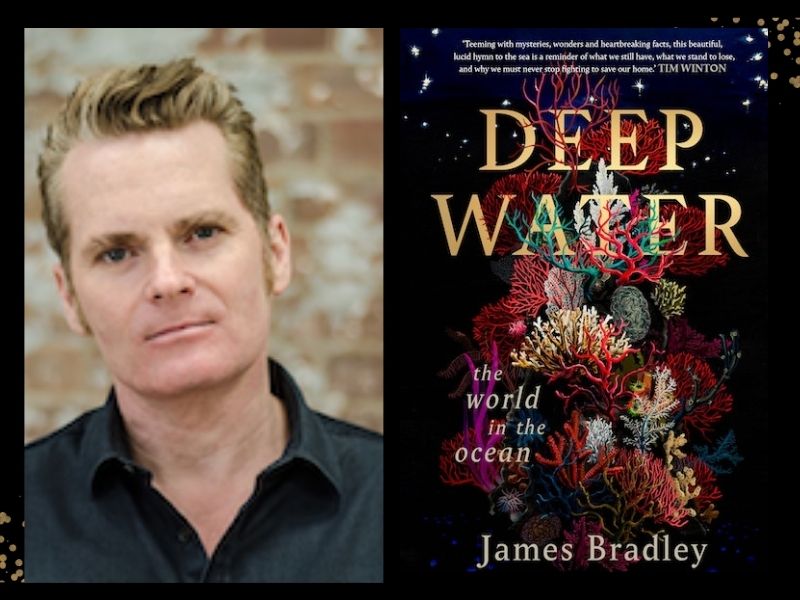

Deep Water: The World in the Ocean is a monumental work that deserves the unbridled attention of every person on the planet. If ever there was a highly readable book that sets out the damage humankind has committed to the Earth, this is it. It is so skilfully crafted, combining anecdotes, proven facts and undisguised speculation about what is arguably the most important and urgent issue of our time – the harm we inflict on the oceans and the consequences that spring from that to the world we live in now.

Apart from presenting factual, well-researched material to the lay reader, what also makes Deep Water so compelling, in spite of the horrendous situations it depicts (that could make any empathetic reader want to look away), is the way Bradley moves effortlessly from the intensely personal to the fascinatingly general – for instance, the fact his brother kisses groupers will segue to an analysis of the sophisticated cognitive abilities of fish.

He connects the past to the present – Apollo 8 to the Earth’s fragility. He connects what is happening, taking stock of himself, to what may happen, taking stock of the planet, and makes connections from a visit to Rotterdam to “containerisation” and its global impact.

He manages to convey the scale of what is happening in understandable terms and makes complex issues clear without talking down to the reader. And he does not preach.

Bradley recounts, for instance, how much he and his dying mother enjoyed watching flickering lights in the waves and sand – lights produced by microscopic single-celled organisms the increasing presence of which ‘is also a harbinger of accelerating environmental devastation’. It is a devastation partly brought about by the warming of the oceans.

He points out that in every second of every day of 2022, the amount of heat the oceans absorbed was equivalent in energy to that emitted by five Hiroshima atomic bombs.

Each of the 14 chapters concentrates on a particular theme. ‘Beginnings’ focuses on the history of the Earth and its oceans, ‘Bodies’ on creatures that swim, ‘Cargo’ on transportation, ‘Net’ on fishing, and so on. This concentration on particular aspects of what has happened and what is happening to the oceans helps the reader to comprehend the immense problems all of us face as a result of climate change.

In the chapter headed ‘Traces’, Bradley recounts what he saw on a beach in the Cocos Islands. He was there to participate in a scientific survey, but was overwhelmed by ‘the sheer volume of plastic on the sand’. He makes a list of what he can see: ‘bottles, thongs, rope, a child’s shoe with the word “happy” printed on it, dozens of thong cut-outs clearly discarded from a factory, pieces of industrial waste, toothpaste containers, toothbrushes, bottles, tyres, plastic buoys, children’s toys, sections of coolant bottles, cigarette lighters, cutlery, inner-sole inserts, as well as the now familiar bottle tops and fragments’. It is chilling.

Bradley brilliantly conveys the scale of what’s happening by communicating that 11,000 years ago, atmospheric carbon dioxide was around 259 parts per million; recently, it was approaching almost double that. This increase, as many have come to know, is causing the rise in global temperature. He points out that during the Pliocene epoch, temperatures were the same as they will be in the direction in which we are now heading. At that time, the ocean levels were about 20 metres higher than they are now. An increase of this order in the oceans’ height would displace many millions of people with terrifying consequences.

In the concluding chapter, ‘Horizon’, Bradley shares his personal view that the ‘storm that is upon us will leave nobody untouched. Surviving it demands we build a world that treats everybody – human and non-human – as worthy of life and possibility. That will not happen unless those of us who have benefited … learn to see our place in the world differently, to recognise the true cost of the lives we live’.

Read: Book review: The Beauties, Lauren Chater

He opines that the fundamental shift in the economy required to avoid massive disaster is not impossible. He concedes there are times when he can convince himself that such a shift could come about because ‘however much is lost, there is still more to save’. I wish I shared even his meagre optimism; that said, his beautiful formulation of the problem arms readers with a way to seize some hope.

Deep Water: The World in the Ocean, James Bradley

Publisher: Penguin Random House

ISBN 9780143776956

Paperback 464pp

RRP $36.99

Published 3 April 2024