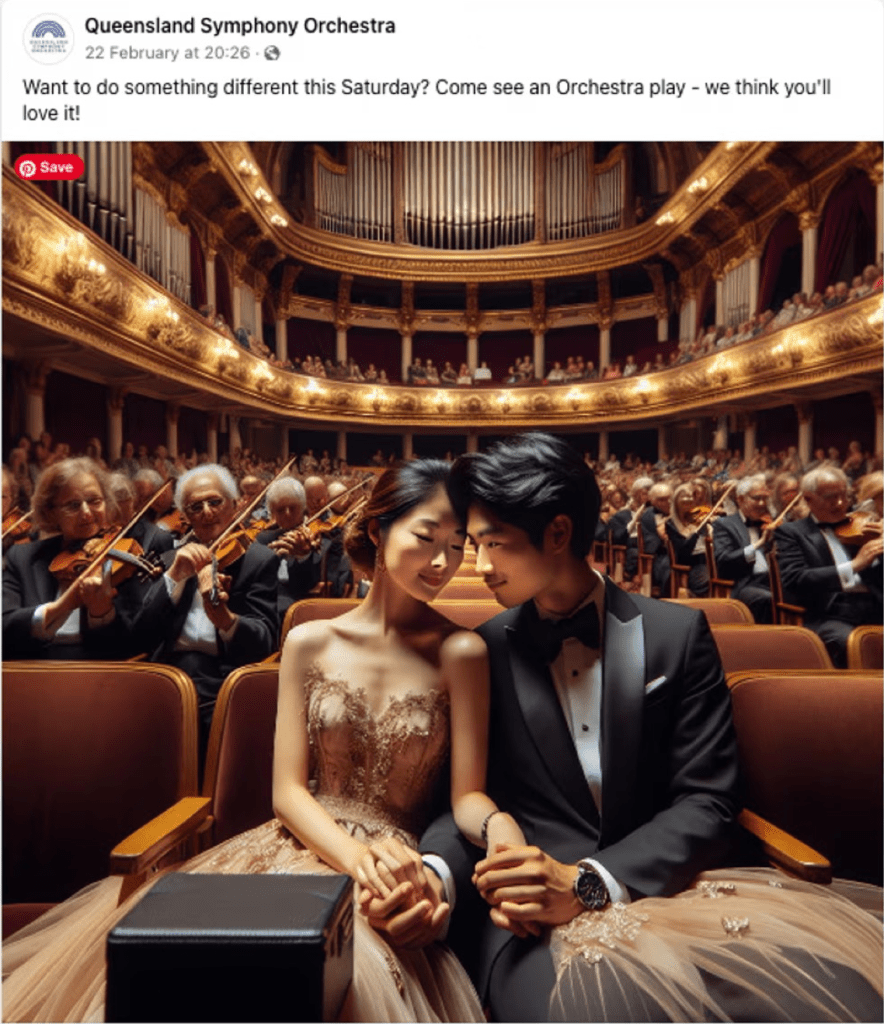

The Queensland Symphony Orchestra (QSO) has come under fire for its apparent use of an AI-generated image to promote an upcoming performance. Commentators noted the improbability of the image, specifically the setting, which features a (clearly) animated couple ostensibly seated in an auditorium surrounded by orchestral musicians; some obvious physical discrepancies are apparent, such as the aggregate and dimensions of the couple’s fingers.

The accompanying copy, too, suggests some form of AI usage: ‘Want to do something different this Saturday? Come see an Orchestra play – we think you’ll love it!’ Both the capitalisation of ‘O’ in ‘orchestra’ and the Americanised ‘come see an orchestra’ do not align with Australian copywriting conventions.

Unsurprisingly, the post has prompted reactive commentary. A phlegmatic statement from the union representing orchestral musicians, the Media, Arts and Entertainment Alliance (MEAA), claims it is the ‘worst AI-generated artwork we’ve ever seen’. The Guardian reports: ‘It is inappropriate, unprofessional and disrespectful to audiences and the musicians of the QSO,’ adding, ‘creative workers and audiences deserve better from arts organisations.’

This kind of rhetoric is notable, given that the MEAA represents both musicians and marketing professionals working in cultural institutions. Yes, the statement focuses on the implications for the musicians depicted in the image – rather than the arts marketers, who are facing increasingly urgent considerations about the future of their roles, given predictions that AI will transform traditional marketing practice.

The post clearly has issues, and some critique is justified. It raises fair questions about the use of AI, its increasing prevalence in creative work, and the likelihood that it will become a permanent fixture in marketing practice. Yet beyond these initial arguments, this situation raises a deeper question that is more relevant to the authenticity of arts marketing approaches. I believe this is an opportunity to reinforce the primary purpose of marketing: to connect products to customers – in the case of arts marketing, to connect cultural experiences to audiences. That’s where the misfire is most relevant.

The challenges of marketing orchestras

Orchestras, like other heritage art forms, face the ubiquitous challenge of building and retaining new audiences. In the orchestral world, marketing is often positioned as the key strategy deployed to build audiences. Equally, marketing is frequently blamed when growth targets aren’t met, rather than orchestras addressing other, more essential questions of engagement, such as programming strategy or the orchestra’s deeper connection with the community in which it exists and operates. Programming is often treated as some form of holy grail in orchestras – an activity that seemingly exists in its own plane, with objectives and criteria sometimes unrelated to the the expectations or needs of the audiences who will attend the concerts. But, when things go wrong – marketing usually cops the blame.

A complex product

Orchestra marketing can be tough. As a heritage art form with its roots in Western Europe, orchestral and classical music have some inherent challenges: accessibility, relevance and antiquated concert conventions such as what to wear and when to clap, all deter new audience members. Threshold anxiety for new audiences is an ongoing challenge that orchestras must constantly address. Thus, orchestral marketing often seeks to normalise the experience of attending a concert – for example, ‘want to do something different this Saturday?’

The ubiquity of orchestras – six state orchestras in Australia alone – with near-identical missions poses a further challenge for marketers. The orchestral product offering can be relatively limited, with programming replicated across decades, the carousel of Beethoven cycles and other canonical repertoire seemingly on rotation, and other campaigns and events repeated annually. This fosters a natural tendency towards unoriginality in creativity and messaging; for example, whimsical variants on ‘Play your part’ for the end-of-financial year giving campaign and ‘Give the gift of music’ for a Christmas campaign as repeated calls to action.

I would argue that the risk of this kind of shallow approach is more of a concern than the use of AI, which itself could be a tool to create richer and more immediate content – with the imperative that it is grounded in a genuine understanding of the art form, its audiences and potential audiences. This is where the QSO example went offtrack.

The desire for authenticity

Overlying all this is the high value placed on authenticity by contemporary consumers. While authenticity has become a buzzword, it is rooted in the shattered trust resulting from major social events of recent years, such as the Global Financial Crisis, where seemingly unshakeable public institutions disappeared overnight. Subsequent events like the #MeToo and BlackLivesMatter movements have surfaced egregious behaviours and challenged normalised power structures. COVID-19 tested trust in government and the nature of human connection in nearly every possible way. Thus, a baseline of scepticism and unwillingness to accept messaging at face value reflects an overarching desire for truth, honesty and openness. This is a key characteristic of modern consumers – particularly younger

generations.

And, like the QSO example, the repercussions can be voluble. Take the backlash to Pepsi’s disastrous 2017 apparent attempt to leverage Millennials and Generation Z’s allyship with the BLM movement. The ad, which was pulled before general release, depicted Kendall Jenner joining a rally for an unspecified cause, breaking the tension of a barricade confrontation with police by inexplicably presenting an officer with a can of Pepsi. This misfire is a perfect example of contemporary consumers’ intolerance for perceived inauthenticity.

Engage with authenticity

Returning to the QSO example, it is a fair assessment that it was not a successful attempt to use AI. However, I would say this is a forgivable stumble in employing new technology, rather than the hyperbolic “inappropriateness” suggested by the MEAA. Certainly, anyone who has worked as a marketer knows the chills elicited when an activation misses the mark or goes out with some kind of indelible flaw. We should consider the well-meaning professional who now finds themselves in the unpleasantness of being at the receiving end of a form of media pile-on.

QSO has a fine track record of marketing campaigns that emphasise the accessibility, enrichment and availability of its music to its community. Its ‘Orchestra for Everyone’ campaign of recent years is one of the stronger examples of an Australian orchestra’s genuine intention to connect with its community. This message was reinforced in its response to criticism: ‘At QSO, we encourage exploration, innovation, experimentation and the adoption of new technologies across all facets of the business. From time to time we will use new marketing tools and techniques as we are an orchestra for all Queenslanders.

A scan of the QSO’s current Facebook offerings (the offending post now wisely removed) shows friendly, inviting posts that reflect the musicians and artistic leadership in everyday performance, rehearsal, and related activity—all of which humanise the orchestra and invite engagement with new and existing audiences.

The situation is a cue for orchestras to genuinely grasp the dynamics of the environments in which they operate and, by extension, their community, audience and potential audiences. By developing this deep understanding, orchestral marketing can transcend the temptation for cliché, shallowness and blandness and create vital, relevant content that is deeply connected to art form and audience. If these objectives are genuine, clearly articulated and intentional, it shouldn’t matter what tools are used to get there. AI is here to stay. The QSO example doesn’t demonstrate the pitfalls of using AI, it underlines the need for a consistently authentic approach.