If there was ever a more resounding endorsement for a show it would be its ability to render a Minister speechless. And that’s exactly what happened on the opening night of Black Diggers at the Canberra Playhouse on Wednesday, 25 March. As Senator the Hon. Michael Ronaldson, Minister for Veterans’ Affairs, ruminated after the show; for a performance as powerful as Black Diggers, there are no appropriate words. Reflection is the only suitable response.

Black Diggers weaves the overlooked experiences of Aboriginal servicemen in the First World War with the more traditional tale of the ANZACS. As director Wesley Enoch contends, the intention was not to rewrite history but to expose a neglected truth. To this purpose, the narrative is deliberately esoteric, like flashbacks of memories lurching from moment to moment in a collection of disparate vignettes. The patchwork quilt representation of history, explains writer Tom Wright, bestows a sense of theatrical shellshock on the audience; challenging the watcher to take on the role of the historian in piecing together snippets of each man’s heroic life.

The extent of research that went into the production was certainly vast. When the War Memorial was first contacted by the researchers to exhume records about Aboriginal servicemen, the original figure of enlisted Aboriginal soldiers was believed to be approximately 400. However, as Black Diggers so hilariously exposes with the character calling himself James Cook, many Indigenous diggers adopted false European names to get around the requirements of the Defence Act (which stipulated that a member of the Australian Imperial Forces must be of ‘substantially European descent’). As a result, a more thorough examination of history has revealed that the actual number of Indigenous AIF may actually be in the vicinity of 1300.

The question of what would compel Aboriginal men to enlist for the forces is intriguingly examined throughout the show. The irony of native Australians signing up to invade foreign lands is cleverly depicted, considering the first scene portrays the brutal murder of a mother and her family. The fact that Aboriginal people were rounded into reserves, deprived citizenship and subjected to indescribable inequality further confounds why so many young men were willing to be involved in a war that was overwhelmingly marketed as a fight for the Empire. However, the marvellous monologue delivered as the address of a returned serviceman explains, war also represented that great equalising opportunity. Here at last was a chance for men to fight for their country, alongside other countrymen. In the paradoxical world of warfare, where confronting death made everyone just a mere mortal, the escapade of war presented the possibility of change.

Tragically, as one by one, the cast members peter back into society, the sad realisation is that of course, not much had changed. Upon returning to their homes, the Indigenous soldiers are still greeted with the unrelenting scourge of racism. Such unquestionable injustice is made evident when the Lands Department relocates Aboriginal settlements to grant the land as a reward to returned servicemen – white returned servicemen. When other characters are treated to similar unequal treatment such as exclusion from pubs, denial of back pay and relegation to menial jobs, various experiences of these Indigenous war heroes proved a stark reminder that more the world changed, the more some things stayed the same.

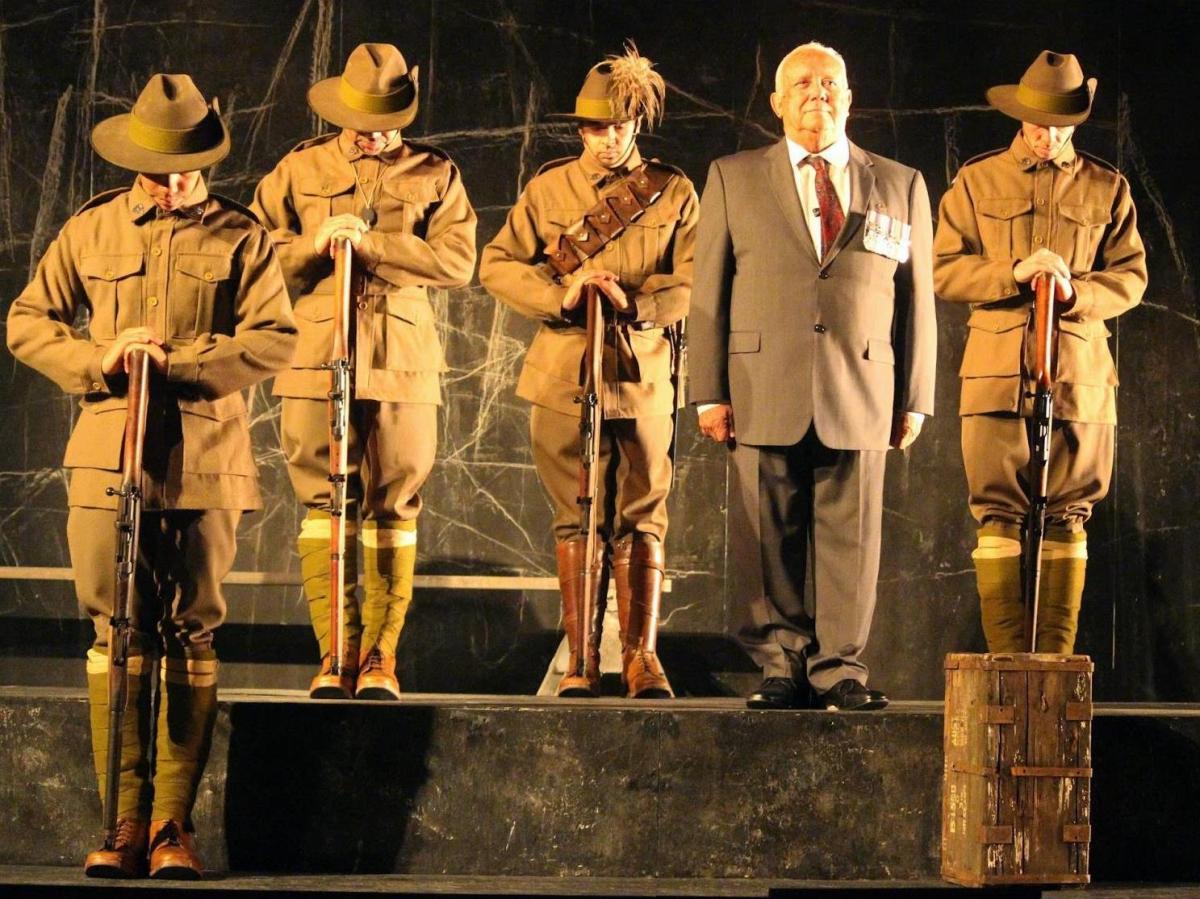

One hundred years after the birth of the ANZAC legend the story of indigenous Australians fighting in World War I is a side of history that is not given much emphasis. In line with our nostalgic recollections of that bygone era, one only needs to saunter up the road to the War Memorial to be greeted with quintessential images of young, Australian diggers, adding to the preconception that the soldiers were uniformly Caucasian. But as the set design shows, history can be constantly rewritten. The backdrop of the performance is a constantly changing treatise to the foreign battlefields that claimed so many Australian lives. Both a metaphor for the whitewashing of history and a symbol for how historical records can be so easily erased, Stephen Curtis’ blackboard scenery provides the opportunity for the characters to write their own stories onto the stage, stories which were too often forgotten in the official annals of WWI records.

After touring most of the capital cities to much acclaim, it is fitting that the show should culminate in Canberra to coincide with the Our Mob Served project being led by Mick Dodson. A joint initiative between the War Memorial, Departments of Defence and Veterans’ Affairs and the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders, Black Diggers brings to life the research being undertaken to uncover the true involvement of Indigenous people in Australia’s military campaigns. The exceptional performances of all of the cast members in re-enacting the lives of those who served demonstrate that the stories of those past are still resonating with us today.

As the curtain closed on the 100 minute show leaving not a dry eye in the house, it became apparent that Black Diggers was an essential recount of not only ANZAC history but the whole nation’s history. It was impossible not to feel moved by this performance. Perhaps it was the sense of injustice permeating throughout the production; perhaps it was the melancholy tribute of The Last Post sounding off the show; perhaps it was the timeliness of a theatrical production where the soil was constantly used as a recurring symbol of the importance of one’s land. Or maybe it was just the simplicity of recognition being given to something long overdue. As I heard one audience member say after the show, “Its about time that story was told”.

Make no mistake, this is ground-breaking theatre. The tragedy of course, is that it shouldn’t be.

Rating: 4.5 stars

Black Diggers

A Queensland Theatre Company production

Director: Wesley Enoch

Canberra Playhouse

25-28 March 2015