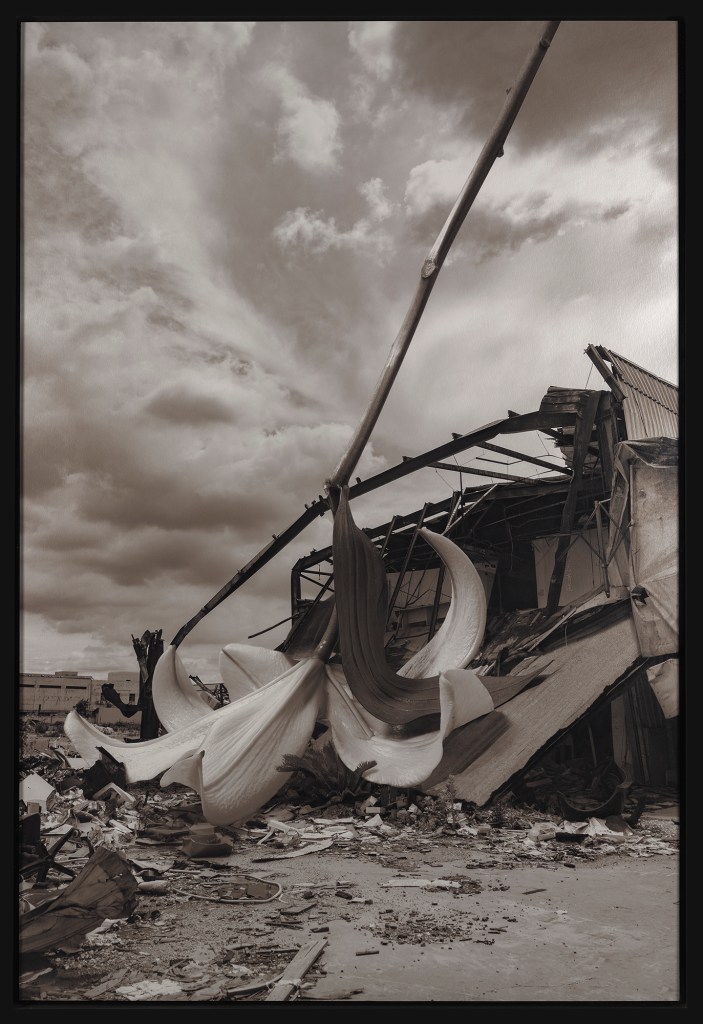

When the smog clears, we expect to see; in the aftermath of change, we demand answers. At least this is the proposition of A Blueprint for Ruins, White Rabbit Gallery’s latest collection on China’s chrome-encased rebirth towards the cutting edge and the metropolitan. Like the ground swallowing itself up, the exhibition deals with what’s left behind in the fissures of change – and what provocations arise against new life overtaking the old.

Curated by David Williams, the collection is part of a two-hander, with the former exhibition, I am the People, influenced by Hao Jingfang’s 2012 novelette, Folding Beijing. In the story, the future is now and Beijing has become a dissection of social class in tightly partitioned spaces. Both exhibitions build towards a larger impetus regarding China’s advancement – in the Tower of Babel, what happens to those who fall in between the cracks?

The artist Chen Wei offers: ‘My life in Beijing is, I think, like being caught up in a sea wave. I am part of something so big that I can neither control it nor step away from it. I have thought about moving away but, no matter how bad it gets, I know I will never leave China, because this is my country.’ A Blueprint for Ruins charts the making of new cityscapes through the artworks of those who were swept up in the process.

Jian Jun Xi’s The Empire (2013) holds court on the ground floor of White Rabbit. It is a vast contraption with a dome-like rotunda modelled after the Greco-Roman architecture of the US Capitol building. At ArtsHub’s viewing, the artwork was rendered in unpainted wood and suspended, supported by grid-like metallic bolsters.

The piece was previously shown at White Rabbit with a performance art aspect, featuring a hand-made bunk room complete with a bed inside the dome, into which the artist himself and participants were invited. Now it is curiously bereft of persons and process, all the markings of the institution reduced to the very building that oversees much of the West’s consolidated power. Living and creating between the UK and China, Xi christens the structure with China’s own lineage of greatness, questioning in what manner does it recall the same beliefs of the American dream? And, without it, how much stands in attention to detail?

Read: Towards continuum: behind the hardware of digital art

Upstairs, glacial debauchery awaits. Chen Wei’s Drunken Dance Hall (2015) tells the aftermath of Dionysian revelry without any of the participants. A club is empty of people and drinks. It is a set that (despite its immobility) feels alive with unseen ghosts. The piece takes inspiration from French poet Arthur Rimbaud’s The Drunken Boat, a self-narrated epic of demise from the perspective of the ship. Here, the walls also speak – they are disillusioned, but grandiose. The artist likens the melancholy of leaving the club to an illusory wave.

Chen remarks, ‘Although this desperate yearning to escape reality is depressing, sad stories can be beautiful.’ Perhaps, in the eyes of those drifting to the wayside, even the brutalist can become poetic. The floor at the centre of the hall is sloped artfully to look like an oil spill. Against it, the neon of the room appears almost navy in the gloss of the condensation. The mise-en-scène is an empty promise, hollowed out by the dreams of those vulnerable to the national psyche and what it demands after daylight breaks through.

On the localisation of Chen’s works for an Asian Australian audience, Williams says: ‘We’ve been working on the installation for over a year so that it more reflects the artist’s contemporary photographic practice. I think the ideas of urbanisation, housing crises, displacement and the ongoing development and expansion of urban areas will connect with the Chinese diaspora in Sydney and also a wider audience of visitors.’

This connection is most compelling in two of the following pieces on the first floor. The first, A Long Day of a Certain Year (2018), is Li Lang’s five-channel video projection, traversing the hinterlands of mainland China. It is stretched like taffy across a black wall, projecting one image per minute across a high-speed railway for 4600 kilometres. The moving images are interspersed in black and white with storied dialogue from over 40 journeyers on their own destinations.

The artist says, ‘In life, ordinary people are bystanders of reality… But don’t forget, the train will eventually reach the end – don’t feel that reality is like the scenery outside the window, quiet and silent.’ One frame capturing a dense cluster of pine trees is captioned simply: ‘Different people can get along with one another.’ The voice work layered on top of the projection is a mishmash of the 40 participants, slipping in and out of narration as the frames flash back and forth. The motion itself is reminiscent of the blur of our own line of vision on a railway, the landscape before us dwindling and reshaping as time chases space.

For Lang, hurtling through life is a form of stasis – we are moving, but by what means? This writer is reminded of Joyce Carol Oates’ Where Are You Going, Where Have You Been? In Oates’ story, the protagonist is drawn to a different destination in a cruel twist of faith. In fact, she leaves against her will in full docility, like a lamb to slaughter. What forces are at play to ensure that we continue to accelerate and reach where we wish to be? With a concentrated, almost suspending, intensity, Lang asks us what our next stop might be when the train shuttles to an end.

A temporal landscape of another kind, Yuan Shun’s Soft Landing (2018) is an apparition of a world in ruins. The scene is a familiar one, conjuring up extraterrestrial and sci-fi compositions of pop culture and film from the mountain caps and craters resting on a valley of sand.

At first, the scene appears pristine, like a movie set. With concentration, the viewer can find shadowy reflections of life. Jutting form-ways and planetary “dust” is ridged with tracks, along with dome-like structures that have been planted – but by whom? There may be whispers of still life, but Yuan proposes the work is a product of ‘China’s Great Leap Forward (1958-1962) generation’, a generation imbued with pride due to the achievements of the national space program (with roots tracing back to the 1950s).

Awash in dark red light, the settlement punctuates topographical space with a weighty, loft-like expression where something exists with resultant power. The very edifice of the model that we see is built atop of unblemished terrain, now giving way to the new constructions that are voluntarily produced by an unknown magnate. We learn that the findings of life on another earth are inconclusive, yet they mirror the very role we play in utilising our speciesism as a birthright to destroy.

Williams says: ‘The character “chai 拆”, meaning “demolish”, can often be found spray-painted on buildings that are due for demolition [in China]. Many inhabitants of these buildings face forced evictions, relocation and displacement. Some people, however, choose not to leave.’ The collection is a taxonomic insight into the persistence of mankind.

Zooming out, A Blueprint for Ruins contends with many through lines. Urbanisation, mass development, migration and progress are all footnotes, but one artistic plot point that floats to the top has to do with good bones.

This snippet of Maggie Smith’s poem can guide us as a scaffold within this very exhibition:

…I am trying

Maggie Smith, ‘Good Bones’ from Waxwing

to sell them the world. Any decent realtor,

walking you through a real shithole, chirps on

about good bones: This place could be beautiful,

right? You could make this place beautiful.

A Blueprint for Ruins is gesturally ambitious, but not a lamentation. For a collection that works around the infallibility of what is now gone, the artworks serve as a tome that heralds what has been lost as a reminder alongside the new.

A Blueprint for Ruins is on view at White Rabbit Gallery, Sydney, from 20 December to 12 May 2024; free entry.

This article is published under the Amplify Collective, an initiative supported by The Walkley Foundation and made possible through funding from the Meta Australian News Fund.