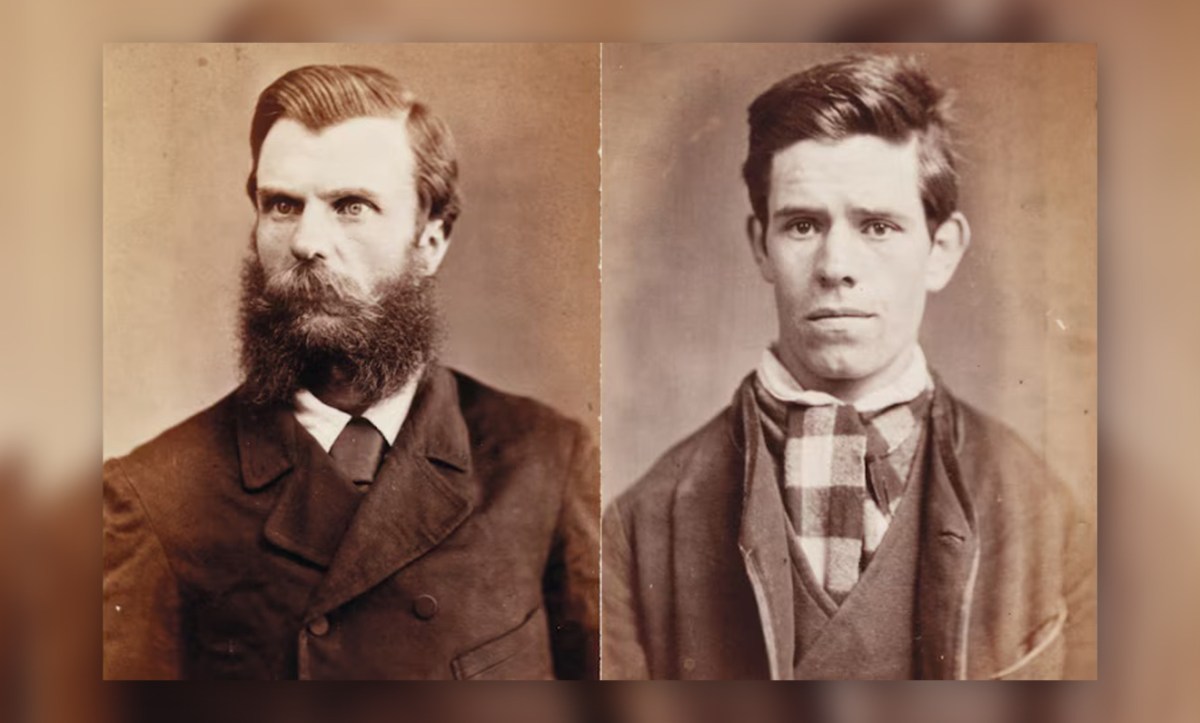

Condemned to be executed in January 1880, in the two months before his death, the Irish-born bushranger Andrew George Scott (aka Captain Moonlite) wrote endlessly from his Darlinghurst Gaol cell about his enduring love for James “Jim” Nesbitt, the young man he met while serving time in Melbourne’s Pentridge Prison a few years previously:

‘Nesbitt and I were united by every tie which could bind human friendship. We were one in hopes, one in heart and soul and this unity lasted until he died in my arms.’

In another prison letter from Moonlite to Nesbitt’s mother, written the day before his execution but never received, having been intercepted by prison authorities, Moonlite wrote (sic):

‘My dearest Mrs Nesbitt,

‘To the mother of Jim no colder address would be true, My heart to you is the same as to my own dearest Mother jim’s sisters are my sisters, his friends my friends, his hopes were my hopes, his grave will be my resting place and I trust I may be worthy to be with him where we shall all meet to part no more, when an all-seeing God who can read all hearts will be the Judge. When intentions will be known and judged of. As to my dearest Jim I have felt that the love and friendship, true, pure, real friendship that blessed our union demands that I should defend his name to the last…

‘I send you some of his hair and will try to send you anything else of his I can get. Give the love of a brother to dearest jims Sisters and to his father.‘Farewell my dearest Mrs Nesbit

‘I am ever to you a loving son in spirit

A.G. Scott’

Moonlite was executed on 20 January 1880 at what is now the National Art School.

James Nesbitt, who had lived with Moonlite in Fitzroy following their release from gaol and followed him faithfully during Moonlite’s brief, abortive career as a public speaker on the issue of prison reform, as well as during their subsequent, ill-fated bushranging spree, was killed the previous November.

Throughout his trial – even on the gallows – Captain Moonlite wore a ring fashioned from a lock of Nesbitt’s hair on one of his fingers. His dying wish was that they be buried together – a wish that was finally carried out in 1995.

Given the facts of their tragic love affair, not to mention Moonlite’s front-page notoriety at the time of his death, why are his exploits so little known today?

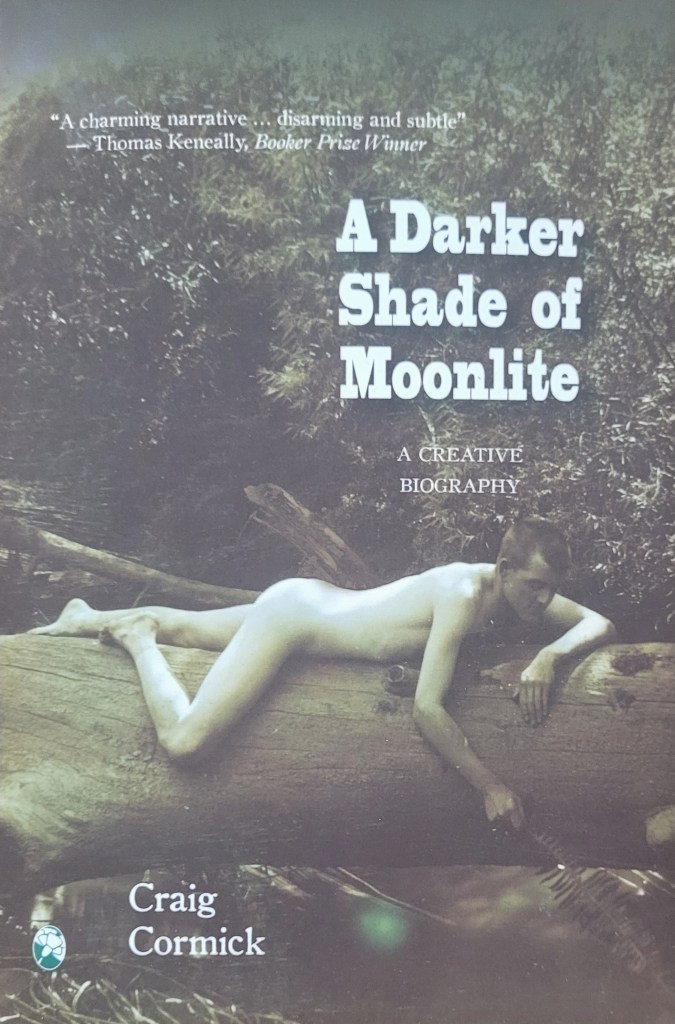

‘Captain Moonlite, at his time, was the best-known bushranger in Australia. He was commanding pages and pages of copy. That all went out the window when the Kelly Gang put on their suits of armour, those iconic suits of armour that we have the capacity to fill with our own imaginings,’ says Dr Craig Cormick OAM, the author of over 30 books of fiction and non-fiction and whose latest book is A Darker Shade of Moonlite: A Creative Biography.

Published earlier this year by Queer Oz Folk (a not-for-profit publisher with a focus on queer Australian history), A Darker Shade of Moonlite draws on Moonlite’s reputation as an unreliable narrator to tell a fresh, frank and entertaining account of his life, love affair and death.

‘He was a highly educated man. He was a scoundrel. He was a rogue. He invented his own history. He was a conman. But his life played out a tragic trajectory whereby the authorities turned against him and would not let him get an opportunity or a chance to get anything right. In the end, Moonlite and a small gang of young men, including the one who he was clearly most in love with, James Nesbitt, walked overland to get out of the Colony of Victoria where they felt they were being persecuted, towards New South Wales,’ Cormick says.

Foreshadowing the Kelly Gang’s subsequent siege of Glenrowan in June 1880, where the gang took multiple prisoners and held them hostage in the Glenrowan Inn – keeping the alcohol and entertainment flowing all the while – Moonlite and his gang bailed up Wantabadgery Station near Gundagai in 1879 after being refused casual work in return for a meal.

Events went terribly wrong, leading to Nesbitt’s death in his lover’s arms, as well as the deaths of 15-year-old gang member Gus Werneckie and Senior Constable Edward Webb-Bowen, in the subsequent shootout.

In writing the story of Moonlite, Cormick says he was specifically interested in bringing a contemporary vernacular to the tale: ‘When we write about the past, we pretend to own the voice of the past … We can put in a “thou” and a “thee” and then pretend it’s the Shakespearean era, but always writing from the present, while pretending to be a voice of the past. So I haven’t even bothered pretending.’

He adds: ‘When you’ve got a history of which there’s lots that is unknown, a historian is sort of limited by needing to work with those parts of the known, [whereas] creatively you can fill in the past. Some historians creatively fill in [those details] when they shouldn’t. So, when people ask me, “Is that fact or is that fiction?” the answer is “Yes.” Because sometimes you need a different approach, and I think we are often far too limited in the types of reading and narratives we have in non-fiction.’

Read: Reclaiming Australian history one gay at a time

Nor is Cormick the only practitioner bringing their creative skills to bear on Captain Moonlite’s tale.

Jye Bryant’s Captain Moonlite – A New Australian Musical was recently staged in an amateur production by Richmond Players in NSW following its premiere season in Queensland in 2020; that same year, author Garry Linnell also brought his journalistic flair to the book Moonlite: The Tragic Love Story of Captain Moonlite and the Bloody End of the Bushrangers.

In 2019, Australian-born and New York-based composer Wally Gunn wrote a 90-minute oratorio called Moonlite, while Melbourne filmmaker Rohan Spong’s ambitious feature Moonlite (adapted from a play by Simon Matthews) was shelved earlier in that decade, having failed to secure the funding required to complete it.

Similarly, the 1910 feature Moonlite, written and directed by John Gavin (one of many bushranger films made before Australian state governments moved to ban such seditious storytelling, severely damaging the Australian film industry in the process) is also lost, save for a few brief fragments.

Thanks in part to historian Garry Wotherspoon’s rediscovery of the Moonlite Letters in the NSW State Archive in 2004, the story of Captain Moonlite has not only been resurrected as an iconic aspect of Australia’s bushranging history, but he is also increasingly being recognised as a definitively queer figure from a period when homosexual and heterosexual identities as we know them today did not yet formally exist.

Visual artist, curator, non-practising lawyer and Senior Lecturer in the School of Art at RMIT University, Dr Drew Pettifer, presented the exhibition Forget Me Not: A queer end to the bushrangers at Melbourne gallery Sarah Scout Presents earlier this year.

Pettifer says it was the silencing of the Moonlite story that first attracted him to the bushranger’s tale.

‘I was captured by this narrative of Captain Moonlite and the ways in which this queer history has been incredibly under[told] – if not untold altogether,’ he says.

‘How he would have identified himself or thought of himself and his own sexuality we don’t know. But there’s clearly a queer relationship between him and James Nesbitt. But also the other angle is from a legal perspective – how so many of these queer narratives are captured in court cases and legal transcripts. And so they’re institutionalised and we [only] see them for a very specific kind of angle,’ Pettifer adds.

Despite the framing of such documents through a legal framework, fragments of the real people sometimes shine through the dry records, he continues.

‘So, for example, Nesbitt had three months added to his sentence for bringing Moonlite a cup of tea while they were in [Pentridge] prison. So these kinds of tender little things come out through the records even though we’re having to read them obtusely, through a queer lens. And my [arts] practice has worked in this kind of way, looking back at these queer histories obtusely, through the angles we can perceive these histories from,’ Pettifer says.

Read: Book review: Secret Histories of Queer Melbourne

One of the central pieces of Pettifer’s exhibition was the recreation of – or creative homage to – the ring of Nesbitt’s hair that Moonlite wore up until his execution.

‘For me, the real anchor of this exhibition [were these] two rings, one cast in bronze, one in gold, partially to represent the social differences in their background. Moonlite was known as the gentleman bushranger and came from a very middle class or upper middle class family. Nesbitt was very working class. So there are some differences there,’ he says.

‘But I’m very influenced by the artist Félix González-Torres who uses ideas of symmetry and sameness as a reference for homosexuality and queerness. And so this idea of having two rings that are the same but different, was quite significant. The reason they’re cast from hair is that when Nesbitt was shot in the shootout and died in Moonlite’s arms, Moonlite took a cutting of his hair – as was quite common in the Victorian era – and he wore a ring of Nesbitt’s hair around his finger until he was executed – so potentially he was actually buried with it.’

The existence of Moonlite’s many letters has certainly rekindled interest in his story and brought new attention to the ultimately tragic story of Moonlite and Nesbitt. Given the richness of the tale, would Pettifer and Cormick like to see this rediscovered queer love affair adapted for the mainstage or the screen – perhaps taking the place of the films that have been lost or unfinished to date?

Cormick says: ‘I think because [Moonlite] hasn’t entered the canon in any way, like other bushrangers, there’s a lot that’s open to interpretation. Now, the question is how well it’s done. Like Oscar Wilde said, even bad poets are sincere. A full-on camp musical about Moonlite, I suspect, might not be the one we’d really like to be watching. But if it was done really well it could be great. It’s really hard to judge something before you see what they’ve done.

‘But there’s a little bit of a resurgence happening at the moment, which I guess [Drew and I] are playing a part of, putting Moonlite’s story back into the vibe-a-sphere of creative production. And I think that creative production often looks for areas that haven’t been touched on well, or are not widely known but deserve to be. So I think that falls into both our motivations. Certainly, he deserves to be better known,’ Cormick says.

Pettifer agrees, adding: ‘And that’s where I’d like to see a fairly substantial, well-made film that actually was able to cross over between the arthouse audiences that are likely to already know some of these histories – or may have come and seen my exhibition or read Craig’s book – and some of the more mainstream audiences that really need to be the people who are able to be connected to these histories and stories that might challenge the historical significance of Ned Kelly vis-à-vis Moonlite, for example.’

Cormick chimes in to add: ‘[Moonlite’s story] lends itself to a less-than-mainstream adaptation. And this needs to happen – by reassessing the past, Australia can figure out where it’s going.’

This article is based on the panel discussion Remembering Moonlite: A Conversation, held at the Kathleen Syme Library, Carlton on Monday 28 August and facilitated by Richard Watts.