Entering the Melbourne Museum foyer visitors are greeted by the smell of popcorn. There are families milling around with excited kids; the building is vast and there is an anticipation of discovery in the air. While that all may match a potential encounter with a massive Mamenchisaurus or looming Amargasaurus, it is perhaps not the environment in which you would expect to find an exhibition of contemporary textile art.

The exhibition Sutr Santati: Then. Now. Next. Stories of India woven in thread, feels both at odds and at home in this environment. It brings together 75 hand-woven textiles created by contemporary Indian designers in celebration of the 75th anniversary of India’s Independence (15 August). Sutr Santati means ‘continuity of thread’ in Hindi, and as one walks around this exhibition that continuity between past traditions and contemporary application is easily felt.

Vogue India has suggested that ‘a textile renaissance has gripped the country,’ that the textile industry ‘lately has entered, perhaps for the first time since Independence, its popular era. Homegrown textiles and crafts are front and centre of fashion and lifestyle brands’ marketing plans and words like thread counts, handspun weaving clusters are part of a new fashion vocabulary’.

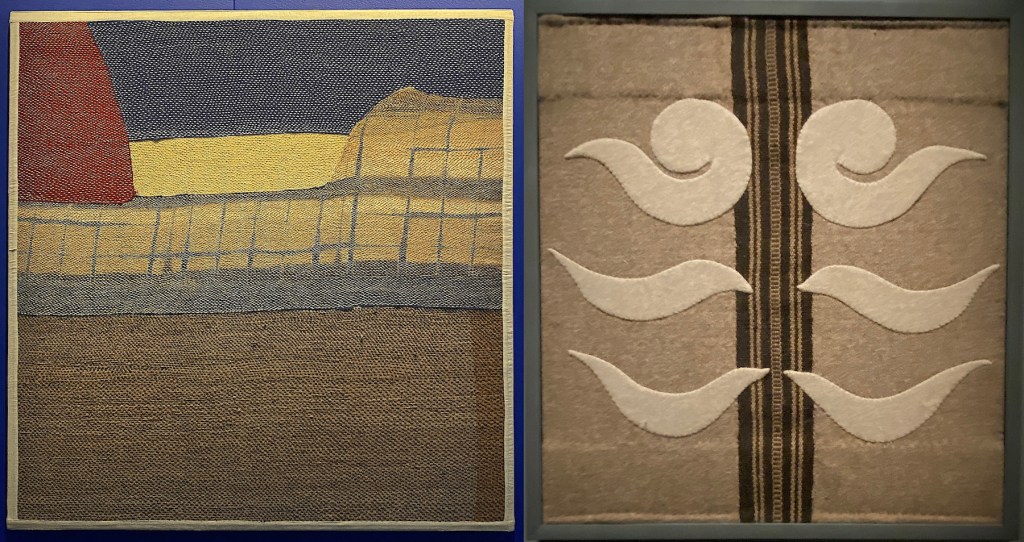

It would seem that Indian textiles are riding a wave with contemporary creatives – one that has moved beyond mere economics and industry. A good example is the Virama wall panel (2022), which welcomes visitors to the space. It appears as any contemporary abstract landscape painting might in an art gallery, but has been created by female artisans from the Indigenous Rabari, a semi-nomadic community from north-west India.

We can get caught up today asking “what’s its story?” looking at contemporary art. Rabari embroidery functions as a form of communication, where motifs, colour and composition signify an individual group identity, occupation or social status. It ushers in a section curated under the theme Red, where several of these textiles carry the big gestural marks we expect of painting.

The exhibition, which has been curated by Lavina Baldota of the Abheraj Baldota Foundation, is navigated by a set of technique-driving themes, some defined by colour, others by social concerns such as Independence, Indigenous Expressions, and the Sacred and Studio.

Baldota explains: ‘The themes, techniques and materials of specially commissioned fabrics in the exhibition are viewed through the lens of innovation. In doing so, they reinforce the value of fabric – an important legacy of Indian independence – to define the country’s contemporary artistic landscape, and to push its creativity into the future.’

Read: What’s going on with textiles art?

While most visiting this exhibition will know little of the history of Indian textiles, what is apparent to all is the incredible skill level. Under the section Texture, works move between the incredible visceral wall panel Fungi (2022) created by designer Vaishali Shadangule from waste scraps to create a work that mimics the textures of fungi, which is said to be a symbol of the afterlife in Indian culture.

There is also a suite of exquisite pieces that take their cue from the hue white, such as ‘Stak Tiger’ (2022) designed by Jigmat Couture, which is inspired by Mahatma Gandhi’s vision of swadeshi (self-sufficiency) and Ladakh traditions, and yet comments on how these textile traditions have been picked up by luxury global brands.

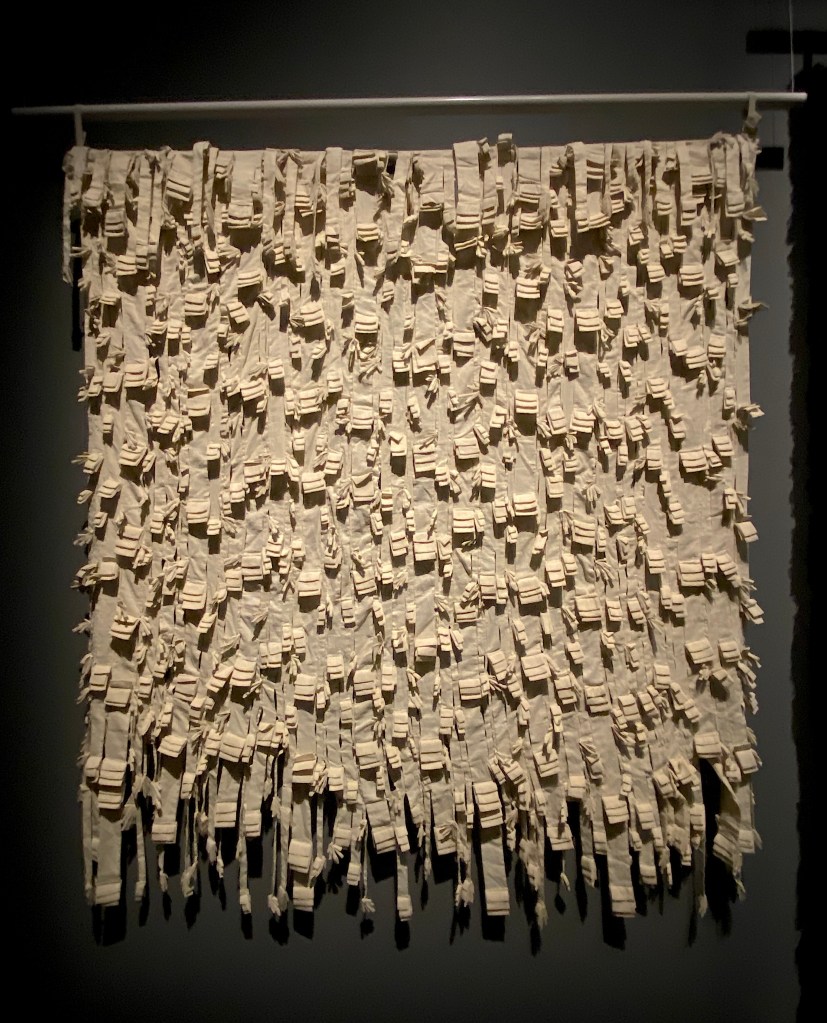

Another textile picking up on Gandhi’s messages of freedom is the hanging Remembrance – freedom – hanging by a thread (2022) designed by Jason K Cheriyan. It uses fine Phulia Khadi (hand-spun and hand-woven cotton) from Sasha, a Fair Trade organisation, to speak to the 75 years of independence. It uses 75 turned strips of fabric to map this history.

Within the section Independence a highlight is the work Freeway (2022) designed by Karishma Swali and created by the Artisans of the Chanakya School of Craft in Mumbai. It comprises many different techniques of handweaving, making the point that the idea ‘unity in diversity’ reflects the spirit of freedom.

Other exciting contemporary textiles are Finding Bapu (2022) designed by Nupur Saxena of West Bengal, Dandi March (2019) a contemporary calligraphic wall panel from Tamil Nadu, to the chunky handwoven tapestry designed by Julie Kagti, In search of water (2022) from Bangalore, which speaks to the crucial element of water in our contemporary world.

Overall, this is a fascinating exhibition on so many levels. It promotes craftsmanship and that place that tradition can still hold in contemporary vernacular, but it also points to shared global concerns – consumerism, ecological preservation, political activism and a rightful journey for respectful identity and independence.

As a whole, it reinstates the value museums play in delivering cultural material to help to understand our world, and locate ourselves within it.

Sutr Santati: Then. Now. Next. Stories of India woven in thread

Melbourne Museum

Until 3 September

Free with Museum admission.

Originally presented at the National Museum of India, New Delhi, this is its second iteration.