In July I was scrolling through Sydney Opera House’s upcoming season of performances and shows – my friend from university was coming up to spend the holidays with me so I was eager to show her Sydney’s finest. Instantly my eye was drawn to one of the upcoming shows: Miss Saigon – an ‘epic love story’ performed by Opera Australia.

My mind immediately went to January of this year when Opera Australia first did a cast call-out for its new production of Alain Boublil and Claude-Michel Schönberg’s Miss Saigon. The controversy surrounding the call-out was of particular interest, bringing fresh perspectives to an old-time musical and drawing attention to the problematic aspects of the underlying storyline and thematic substance of the production.

Recently, Australia has witnessed an explosion of wonderful art from diverse writers and creatives. Only last year Darlinghurst Theatre Company put on Aran Thangaratnam’s Stay Woke, and Michelle Law’s Miss Peony is currently touring to Canberra Theatre Centre, Merrigong Theatre Company in Wollongong and Geelong Arts Centre, among many other locations. So, with this influx of raw, authentic and confronting art by diverse writers, why are shows like Miss Saigon still taking centre stage, and using up stage time that could be given to diverse creatives, or simply better shows that do not perpetuate racist stereotypes?

Miss Saigon is a show that has been controversial since it first opened in London in 1989, when white British actor, Jonathan Pryce, wore prosthetics to change shape of his eyes, and makeup to change his skin colour – in an attempt to make him appear like the scheming Eurasian pimp called the Engineer that he was playing.

However, a more pointed criticism of the show’s subject matter suggests deeply problematic issues – particularly in its portrayal of both Vietnam and Vietnamese people.

Erin Wen Ai Chew, national convener for the Asian Australian Alliance, has argued: ‘One of the biggest reasons [for the criticism] is the negative racialised stereotypes that it perpetuates, particularly about Asian women.’ She explained that this is developed from the racist view of Asian women as sexual objects for American men and soldiers, in the context of conflicts like the Vietnam War, the Korean War and World War II.

Read: Complicating Vietnamese diaspora stories for the better

The delicate balance of restaging classics

There is the argument, however, that Miss Saigon has evolved and been adapted to include an appropriate Vietnamese Australian cast for Opera Australia’s 2023 rerun of the show. But does this suddenly make it all OK?

Unless Opera Australia decides to rewrite some of the most problematic themes of the play – namely the infantilisation of Asian women for the pleasure of American men, and the idolisation of “the West” at the expense of “the East”, as a place of autonomy and freedom, I don’t see its renewed appeal. Let’s not forget, this takes place in 1975, only a few years after the peak of the Civil Rights movement in the US, triggered by the degradation of African Americans and breaches of many fundamental human rights in this supposedly revered pinnacle of the “civilised West”.

Revisions and renewed adaptations are not uncommon. In 2022, the Sydney Theatre Company (STC) had a go at adapting Shakespeare’s The Tempest and rewrote the play’s villain, Caliban. The STC presented Caliban as a victim of colonisation, using creative licence to make the character deliver an impassioned speech from Shakespeare’s Richard II about the forceful and violent occupation of his land by the play’s mainstream hero, Prospero. After all, it is the stories of the victors that are so often told in the deliverance and record of history. Upon seeing the production, the rewrite proved to be effective.

Yet it seems Opera Australia hasn’t planned to do anything similar – at least not to that extent.

So rather than give precious stage time to outdated shows like Miss Saigon, perhaps we can and should turn to other clever adaptations of the old classic.

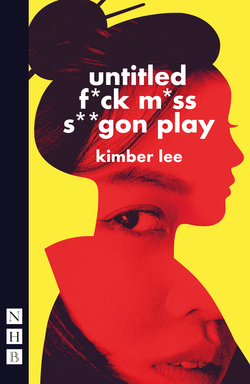

This year, New York-based playwright, Kimber Lee, wrote a parody of Boublil and Schönberg’s musical called Untitled F*ck M*ss S**gon Play. The blurb reads: ‘Kim is having one of those days. A terrible, very bad, no-good kind of day, and the worst part is … it all feels so familiar. Caught up in a never-ending cycle of events, she looks for the exit but the harder she tries, the worse it gets, and she begins to wonder: who’s writing this story? She makes a break for it, smashing through a hundred years of bloody narratives that all end the same way. Can she find a way out before it’s too late?’

The satirical play went on to win the inaugural Bruntwood Prize for Playwriting 2019 and was this year directed for the Royal Exchange Theatre as part of the Manchester International Festival.

These are the shows that revered institutions like the Sydney Opera House need to platform. While an argument may be made that timeless classics deserve their stage appearance, it must be questioned – at whose expense? And are such musicals still capable of receiving the popular reception they once did?

By no means should we boycott the production of all timeless classics – after all, only last year was I fan-girling over Andrew Lloyd Webber’s The Phantom of the Opera, also staged by Opera Australia at the Sydney Opera House. However, we must remain steadfastly critical of works that don’t speak to audiences in the same way they once did. More so, we need to platform the voices of those who seek to make these criticisms, like Kimber Lee.

So perhaps I’ll save the $269 that it would cost me as a student to see Miss Saigon, to instead watch a couple of shows by other young creatives of colour, which reflect the explosion of diverse art that represents more multifaceted and authentic intersections of Australian life.

This article is published under the Amplify Collective, an initiative supported by The Walkley Foundation and made possible through funding from the Meta Australian News Fund.