Signalling an end to the White Australia Policy’s closed borders, the surge of Vietnamese refugees in the 1970s and 80s is undoubtedly significant, and deserves memorialisation in the arts. Yet reducing Vietnamese stories to merely those of war or Asian migrant success is as dangerous as it is common. It paints a misleading and homogenous picture of a complex community with vastly differing experiences.

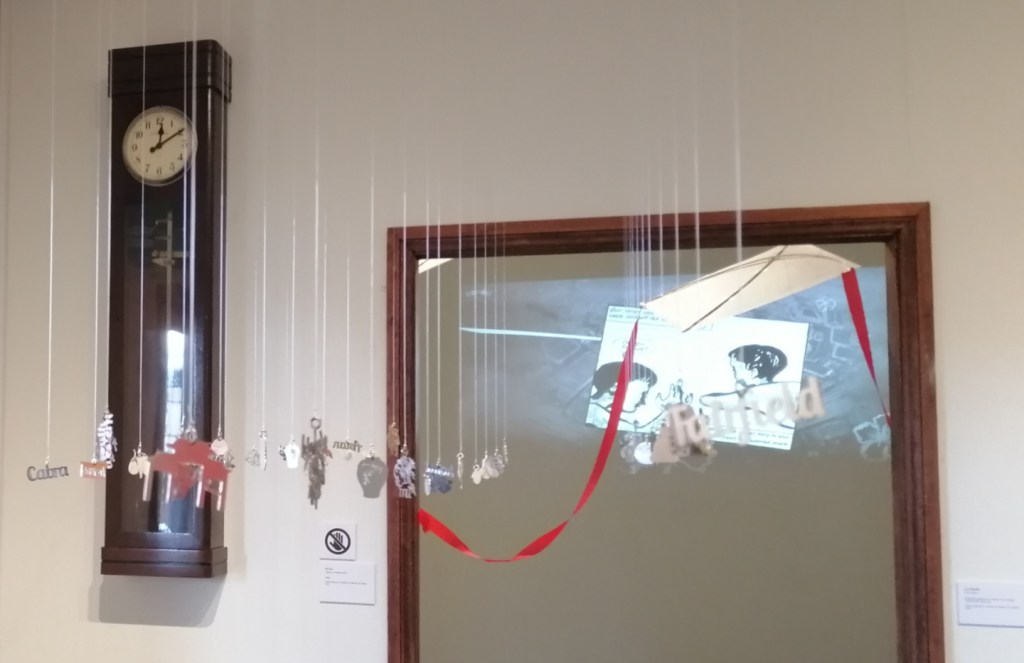

As such, it is no surprise that MÌNH, a word layered with meanings, prominently stands as the title of an exhibition at the Fairfield City Museum and Gallery (FCMG) that presents Vietnamese Australian diversity. Just as the hybrid word “mình” cannot be narrowed to a single aspect of identity – whether used to refer to one’s physical body, possessions or as a term of self-address – the Vietnamese identity also cannot be simplified to a singular story.

MÌNH is an everyday word, which refers to our bodies and selves, but it also means us – about who we are as individuals as well as how we exist together.

Fairfield City Museum and Gallery

A picture into the birth of MÌNH

Curated by Sheila Ngọc Phạm in collaboration with FCMG, MÌNH displays works from 17 writers and artists of Vietnamese or Hoa descent. It is the first exhibition of its kind in Fairfield City, in Sydney’s Western suburbs where Vietnamese is the largest ancestry and which houses Cabramatta, a suburb renowned as Australia’s “Little Saigon”.

The idea for MÌNH arose when historian and FCMG curator Alinde Bierhuizen went through the museum archives and realised that they had never really had an exhibition about the Vietnamese. There had only been smaller exhibitions focusing on individual artists like Matt Huynh and Bic Tieu. Realising the big gap, FCMG decided to collaborate with Phạm to put on something more ambitious about Vietnamese Australians.

What came out of this collaboration is MÌNH, a nuanced exploration of Vietnamese Australian identity, accompanied by several programs and a ‘nice thick catalogue’ including commissioned essays, Phạm tells ArtsHub. She explains: ‘It’s not about Vietnam; it’s actually about the diaspora, the one thing that ties us together.’

MÌNH is also inextricably linked to the Fairfield area as the creative works all have some connection to Southwest Sydney.

Given a platform to capture the Vietnamese identity, a major objective of the exhibition then became to ‘represent different facets of the Vietnamese experience’ and to ‘make our identity seem more complex rather than simplified’. Pham explains, ‘I think there’s a real danger, even sometimes among Vietnamese Australians, that if we just frame ourselves in one particular way, it actually boxes us all in… I want to try to break that box.

‘There are a lot of different aspects to the Vietnamese and I think that’s really important. I always want to emphasise in all my work I write and do, that we’re not some monolithic group…We need to be seen just like everyone else, multifaceted with different histories.’

So, how does MÌNH present Vietnamese-Australian complexity?

The dedication to challenging perceptions of a unified Vietnamese experience has meant each work in MÌNH explores very different aspects of diasporic life. Phạm says: ‘I wanted to tell a story of artists through the generations. Now in Australia, [those in] the Vietnamese diaspora have been here for basically more than 50 years, most coming from the late 70s to the early 80s.’ Including artists from varying backgrounds and ages, each work in MÌNH delves into very different ideas expressed in various styles and mediums.

‘I didn’t want to tell anyone that you need to say anything in particular… I understand there’s something a bit uncomfortable in doing an exhibition just based on identity as opposed to a theme. I did want to keep it pretty open,’ she adds.

Unique aspects of Vietnamese identity are showcased at the centre of the exhibition in a collection of antiquities. These include Vietnamese ceramics (Gốm cổ Việt) and Đông Sơn bronze drums, which were obtained through a community-led project run by artists to “rematriate” or make accessible items of significant cultural heritage.

Phạm continues: ‘[You] walk in and then the first thing you see are ancient Vietnamese objects because I really wanted to say that this is where it all starts with the Vietnamese… It doesn’t start in 1975, it starts a couple of thousand years ago in the Delta, where we’re creating these artistic objects.’

Another important decision was the inclusion of artists from Hoa backgrounds, Vietnam’s ethnic Chinese community. Despite many Hoa people living in Australia, very little discussion exists about their relationship with the Vietnamese identity.

‘I insisted that we really need to look at the Hoa, because I feel like that has bothered me for a long time – we don’t explain that connection very well. I think it’s obvious to a lot of us inside the [Vietnamese] community … and I’ve always found that interesting, that part of the story about Vietnamese history,’ says Phạm.

She further explains that the different works reflect diversity within the Hoa themselves, with a multitude of linguistic backgrounds being represented. This includes Hoa artists Bic Tieu and Christina Huynh who are Teochew speaking, Garry Trinh and Dacchi Dang who are Cantonese speaking, as well as My Le Thi who is mixed Chinese and Central Highlands Vietnamese.

Even among the ethnically Kinh Vietnamese majority, there is a wealth of experiences. ‘They come from different parts of Vietnam, too,’ says Phạm. ‘So that’s another thing that we don’t probably talk about enough. There’s the North and South, and there are other parts of the country as well.’

Importantly, MÌNH does not ignore the trauma of war, though it often dominates discourses around Vietnamese Australian identity. In MÌNH, however, it is limited to one work: Phuong Ngo’s Article 14.1, which uses a funeral ritual of burning hell money. The notes are folded into origami boats to honour the 500,000 people who died at sea fleeing Vietnam.

Phạm says: ‘We could shape the entire discussion around the trauma of the Vietnamese community, but it’s not totally true.’ This is because people have faced different experiences depending on their social class back in Vietnam.

Phạm deliberately included Ngo’s work because ‘I wanted one story representing the boat journey’.

‘It’s definitely not everyone because many Viets came after this whole time, but it’s still an important part of how the Vietnamese even ended up in Australia due to the refugee crisis,’ she says.

Phạm continues: ‘I think that emphasis on difference is really important, because it provides a more nuanced perspective.’

MÌNH through a writer’s lens

Writer Lucia Tường Vy Nguyễn, whose piece L*ve P*em is displayed as one of a suite of four poems, reflects on her participation in MÌNH.

I guess it felt like being part of a connective tissue to make this work that exists in close proximity to other works,’ Nguyen tells ArtsHub. ‘I think it is quite difficult to cultivate a sense of Vietnamese solidarity … you already see that in the Vietnamese Kinh and the Hoa being separated.’

Nguyen adds: ‘I feel that is quite a fractured culture to be honest, so it was affirming and expansive to be in a space that resembles a family house, a real domestic space, with other identities that are perhaps also grappling with Vietnamese-Australianness.’

Nguyen’s work, L*ve P*em, itself relates to an aspect of the Vietnamese Australian experience that is not normally discussed and also informed by her Catholic upbringing. At first glance, it is about “the act of censorship of swear words” in the Vietnamese language that parents teach their children to speak.

In addition, Nguyen explains her poem as an expression of her frustration with the ‘fear of shame, public humiliation or embarrassment that gets perpetrated in many Vietnamese families’. This arises from the pressure of adhering to ‘how respectability politics work with Asian-Australians in the media,’ including being well-presented or compromising.

She adds that it also is a testament to ‘the sort of bootstrap stories of Vietnamese boat people who come and set up 10 different Banh Mi stores and they’re upheld as stories of migrant success and the Australian dream, whereas it’s much more complicated than that.’

In response to whether she believes diasporic exhibitions like MÌNH should be more widespread, Lucia emphasises that ‘more space should be afforded to artists that have been historically marginalised.’ Referring to neoliberal multiculturalism in which Australia accepts migrants for their economic contributions, Nguyen stresses that minority artists should be ‘given space to play without justifying why they’re using up resources’.

However, she is ‘undecided on whether it should be grouped as all Vietnamese artists’ and instead advocates for ‘exhibitions that mix various minority artists who might explore a similar theme or area of inquiry’.

Nonetheless, MÌNH is a step in the right direction, being an exhibition that allows Vietnamese Australian artists to express themselves freely, and which breaks down conceptions of a homogenous Vietnamese identity.

MÌNH is free and will be displayed at Fairfield City Museum and Gallery until 14 October 2023.

Looking For You – Tìm Hiểu will be screened at FCMG on 29 July at 6pm. Reservations are essential.

MÌNH Community Day will be held at FCMG in late September.

This article is published under the Amplify Collective, an initiative supported by The Walkley Foundation and made possible through funding from the Meta Australian News Fund.