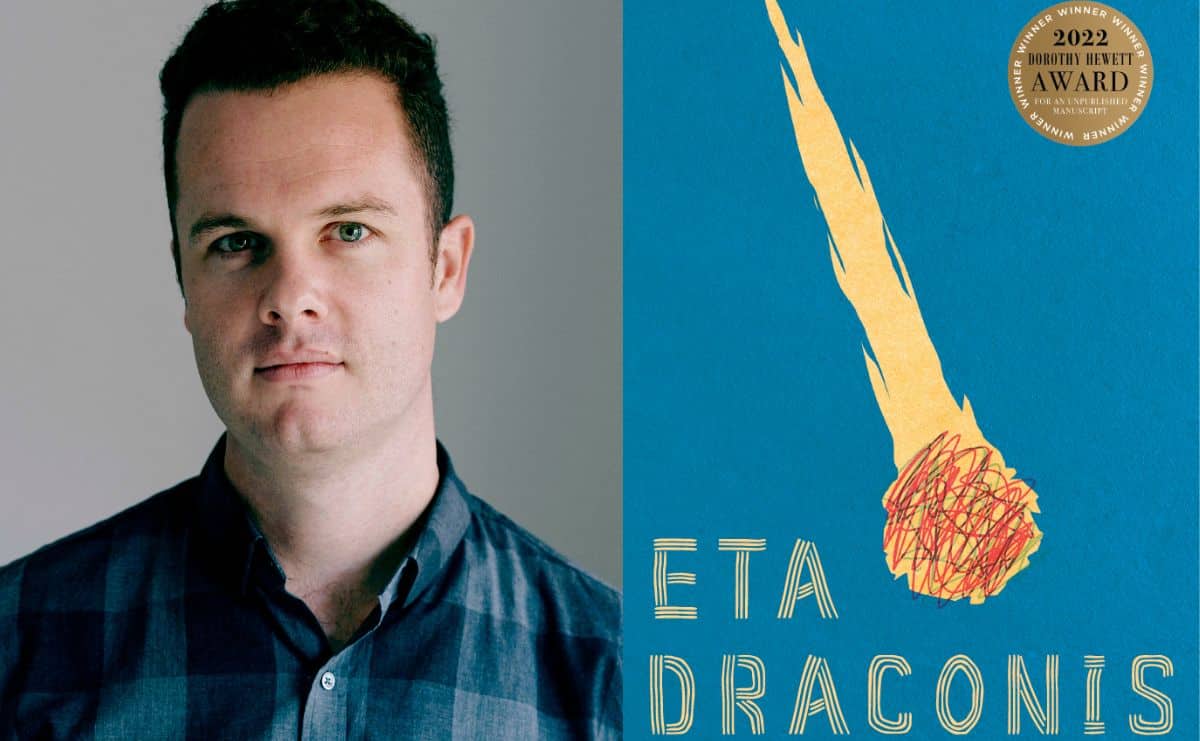

Eta Draconis, Brendan Ritchie’s third novel and winner of the Dorothy Hewett Award for an Unpublished Manuscript, is set in Australia in what appears to be the near future. For several years the world has been experiencing near-constant meteorite strikes from the shower known as Eta Draconis.

Ritchie’s protagonists, Elora and Vivienne, are sisters whose parents fled from the city to Esperance at the beginning of ‘Draconis’. Vivienne, the elder sister, returned to the city for uni as soon as she could, while Elora completed high school in Esperance. As the novel starts, Elora is joining Vivienne on a roadtrip to the city, preparing to begin university herself.

Although the existential peril in the novel is created by meteorite strikes rather than climate change, the novel’s themes fit quite neatly into the nascent genre ‘cli-fi’. I initially assumed that Draconis was a straight analogue for climate change as in the film Don’t Look Up, which covers similar territory, albeit with less nuance and human feeling than Ritchie is able to provide. However, Ritchie wants us to consider climate change explicitly. When the sisters are driving through the ‘dry and barren’ Wheatland, he has Elora reflect ‘that Eta Draconis masked the real crisis gripping her tiny, battered Earth’.

Personally, I am not sure that this overt invocation of global warming was necessary to make the point, but if there were any doubt about where the novel’s sense of existential dread comes from, I think this passage resolves it.

Even so, Eta Draconis is less concerned with politics than how someone in Elora’s position, at the threshold of life on a planet seemingly on the brink of oblivion, can go about living. Vivienne has already resolved to live as if Draconis is not happening, looking only forward, determined not to retreat from the city as her parents have done.

As in Balzac, the city serves as a metaphor for taking control of one’s life, with all the attendant risks and rewards. One unresolved question in the novel is why their parents left the city, and why others choose to live even more remotely in national parks. Ritchie tells us the ‘meteorites had as much chance of striking in these isolated national parks as they did in Melbourne or Manhattan, yet somehow these people found solace in the space and quiet’.

Perhaps close encounters with death have led people to re-evaluate what they want from their lives, or perhaps Ritchie is suggesting that our reactions to disaster are inevitably irrational. Because I found this aspect interesting, I would have appreciated more space being given to Elora’s parents, and the friends she left behind in Esperance. However, the novel belongs to Elora and Vivienne and their attempts not to be cowed by the world in which they have found themselves.

Read: Book review: The One Thing We’ve Never Spoken About, Elfy Scott

Elora has decided that she wants to study drama, not a popular choice when society’s singular focus is on responding to Draconis. Her English teacher tells her it is naïve to enrol in an arts degree while the world is on fire. The novel’s most moving passages are those that vindicate what I take to be its central theme: a defence of the role of art in a world on the brink of catastrophe. As Elora reflects, watching the meteor showers overhead, ‘If they were to become extinct, it seemed important to leave in the manner with which they had arrived. To be looking. Thinking. Reaching.’

Eta Draconis, Brendan Ritchie

Publisher: UWAP

ISBN: 9781760802615

Format: Paperback

RRP: $32.99

Release Date: 31 January 2023