Last week, the First Nations Arts and Culture Awards, otherwise known as the Red Ochre Awards, were announced. The awards are held on 27 May each year to mark the anniversary of the 1967 Referendum and the start of National Reconciliation Week.

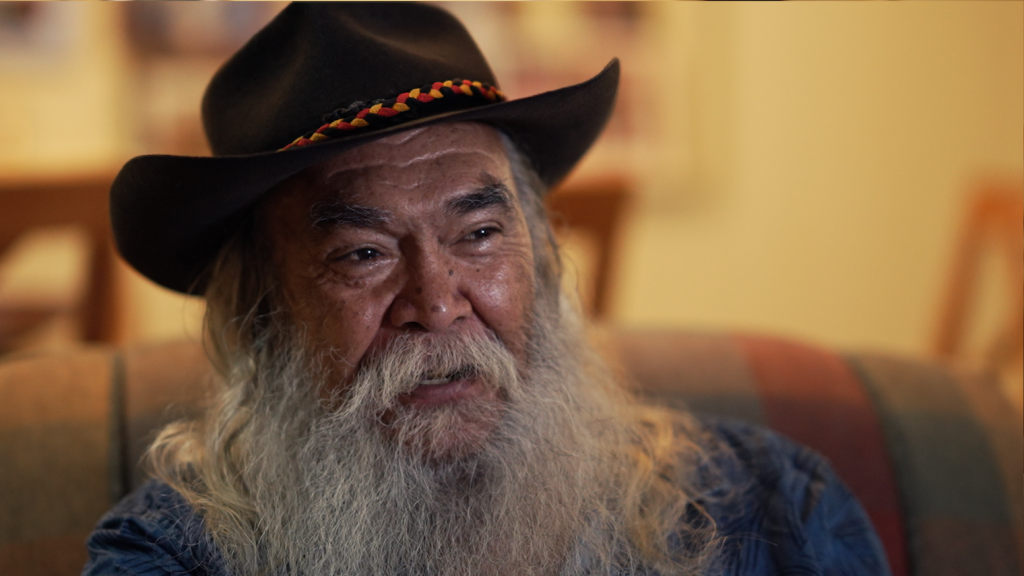

This year, it is fitting that writer, musician, performer, activist and Kamilaroi elder Uncle Bob Weatherall – a pivotal figure in advocating for cultural rights, cultural education and the repatriation of ancestors and cultural material – was celebrated with a Lifetime Achievement Award.

Alongside him, Wardandi elder and artist Aunty Sandra Hill was also awarded for her outstanding lifetime contribution – as an artist who has used storytelling to encourage truth telling and education through her paintings, as well as championing First Nations visibility through public artworks.

ArtsHub catches up with both Hill and Weatherall to learn why community and reconciliation continue to be the key factors that drive their creative practices.

Putting mob first

The first thing Weatherall stresses is that the award doesn’t belong to him alone. ‘If you recognise me, you have to recognise them – the old men and women who went overseas and worked to bring home our ancestors, the old land rights campaigners, men and women of the NAC (National Aboriginal Conference) and ATSIC (Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission), the Kimberley Land Council, the National Federation of Land Councils, FAIRA (Foundation for Aboriginal and Islander Research Action), the Tasmanian Aboriginal Centre and the Centre for Indigenous Cultural Policy.

‘These organisations were instrumental in the establishment of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples,’ continues Weatherall.

‘It was an enormous amount of work we all had to do back then,’ he says, adding that many of the old people have gone, but ‘many are still here working towards a treaty’.

Hill says the most important aspect of the award for her was its validation. ‘For all these years I have painted and not known what people think about it. I like to think it has made a difference, and this validates that it has been noticed.’

Weatherall also speaks of validation. ‘In Queensland, under the Acts, Aboriginal people had all their human rights and fundamental freedoms denied them. My life has been devoted to fighting for Aboriginal rights and self-determination, which includes ownership, control and management of their lands and waters, and to enable Aboriginal artists and traditional owners to be able to showcase their own cultural and artistic expressions in their own theatres, galleries and museums.’

He adds: ‘We are working on establishing the National Indigenous Arts and Cultural Authority (NIACA).’

It is this spirit that is core to First Nations thinking. Hill explains: ‘I’ve never jumped up and said “look at me” – culturally this is not our thing. The Red Ochre – it is about my art and those stories. It is not about fame or glory; it’s about people seeing it and learning something of our history, which is still not being written in the storybooks.’

Hill describes her celebrated Homemaker series of paintings as a ‘visual essay of our culture, and what we have come through and survived,’ adding that, ‘we have come back stronger. We are excelling because we are fighting it, and that is a very powerful thing that art can do.’

In a similar way, Weatherall speaks of the role of repatriation. ‘I have been focused on the repatriation of the ancestors and secret sacred objects from world museums and the 11,000 unprovenanced remains in Australian museums, universities and private collections. The Indigenous Repatriation Program used to be Aboriginal community-based and community-controlled. Under Liberal Coalition Governments – for the last 10 years under former Prime Ministers Abbott, Turnbull and Morrison – control is back in the hands of government and scientists.

‘Traditional Owners are merely stakeholders, rather than those who have primary kinship roles and responsibilities for their ancestral dead,’ he adds. ‘Restless Dream was the same campaign, done another way. Through collaboration with Halfway and musician William Barton, it was a new way to maintain the campaign to repatriate the ancestors. Through an arts focus on music, song, dance and spoken word, we reached out to a new and wider audience,’ Weatherall explains.

Why now is the right time for recognition

Weatherall’s love of theatre and music has consistently informed his life as an activist and advocate. ‘To know the people in the communities [is vital], and knowing their needs and aspirations, to then make sure of those basic human rights, like land rights and the return of our ancestors or the removal of the apartheid laws.

‘If you burn a church down you can rebuild it, but with an Aboriginal site, once you start to injure it, it is a psychological warfare,’ he explains.

In a similar way, Hill describes making her paintings as very traumatic. ‘Once I paint a work, I let it go; it’s been a total healing process. In a selfish way, it is about me getting rid of the pain of the past and the loss, and paying homage to our mob and their bravery and survival instinct.’

She continues, ‘The racism is everywhere; I will use my art to fight it.’

Both Hill and Weatherall believe the timing of this year’s Red Ochre Awards offers an important moment as Australians prepare for the referendum for an Indigenous Voice to Parliament, and it also marks the 50th anniversary of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Arts Board of the Australia Council.

‘More than ever, First Nations knowledge is increasingly recognised as providing valuable insights and perspectives to traditional Western modes of thinking,’ says Australia Council Executive Director First Nations Arts and Culture, Franchesca Cubillo, adding that acknowledging and respecting First Nations cultures is vital for Australia’s social well-being.

Over 30 years, Hill has created 53 public artworks interpreting significant cultural and historic sites throughout Noongar country. They have responded to, and expressed the voices of, the Elders and community through some of the most important periods in Western Australia.

‘It is a level of pride, and just jumping up and down in a quiet way, to put our culture out there, telling those stories and having a physical presence in the urban environment,’ Hill says of her works.

‘You can’t not see it, or unsee it! I have fought every step of the way with public art to make a space for us in the public domain – to be visible in the community spaces,’ she adds. ‘For me, to get this award now, is important because there is a movement in the wider community. I never thought I would see some change for the better for our mob, when you live a lifetime of negativity.

‘There is a groundswell – not just from the non-Indigenous, but from the Aboriginal people in Australia as well. We all want change, I think.’

Weatherall agrees that the struggle against racism is more important than ever in the face of the referendum. ‘You don’t alter the rights of people for a government statistic. Until we have proper legislation of our sacred sites and human remains, and manage control out of white hands and white museums, then we don’t have basic human and cultural rights. We’ve got to let the kids know.’

Nurturing new culture alongside old

Weatherall’s life’s endeavours have been driven by a fight for change, for the reclamation and transmission of knowledge for future generations. His advice is to ‘keep making culture’.

‘If you enjoy it, improve it, turn it inside out and upside down, and create something from it,’ he says. ‘It is our own expression, from our own life, and it means something.’

His words are echoed by Hill. ‘[It’s important] to stay authentic and find your creative place; tell your stories and don’t be afraid to get it out there and do it in your own way – don’t follow,’ she says.

She adds that the pressure to conform is very strong for young mob. ‘All the teaching, the making and trying to get them to be strong in their creativity, is so they don’t go to the white side.’

Weatherall says: ‘A lot of children don’t have a clue what old people went through and we have to give them a black consciousness… You should have the right to be able to fulfil those responsibilities in your customs and traditions, to build new countrymen, a new nation and to always be relevant – being the oldest living continuous culture.’

‘Arts is so powerful and the younger ones need to know how powerful it is,’ Hill says, having the final word.

To learn more about the Red Ochre Awards and other 2023 Award recipients.

The Red Ochre Awards were established by the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Arts Board in 1993 to pay tribute to a senior Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander male and female artist. The recipients receive $50,000 each.