This year’s crop of Archibald, Wynne and Sulman art prize winners were recently announced. They were followed by the Archies alternative, the Salon des Refusés at S.H. Ervin Gallery, adding another 59 portraits to the Art Gallery of NSW’s cut of 57 finalists – making up the ‘Year of 2023’.

Add to that, the concurrent exhibitions Portrait23 at the National Portrait Gallery in Canberra, The Lester Prize: Black Swan Years Retrospective at Perth Town Hall, as well as Archie 100: A Century of the Archibald Prize touring nationally, and 2023 is a very good year to ask what role genre prizes play today.

While we can to and fro over the merits of inclusion – and the winners of these high-dollar prizes – there is a different conversation that has been prickling my thoughts this year. The categories around Australia’s top genre prizes are feeling increasing rubbery.

In short, this may not be a bad thing. But it does indicate how strategic prize entry has become, and how artists are using prizes as a way to buck accepted traditions, and use established platforms for their own dialogues.

Read: Who are the 2023 Archibald, Wynne and Sulman winners?

Notably, this year marks the highest number of Aboriginal finalists in the Archibald, Wynne and Sulman Prizes collectively (around 38%) since the Prizes’ inception (1921 for the Archibald, 1936 for the Sulman and 1897 for the Wynne), an engagement largely led by the Wynne Prize. There have also been the highest number of entries by neurodiverse artists and artists with disability, keenly advocated by collectives such as Studio A.

There is an overwhelming sense of a flattening of the field, one that is keenly inclusive. Add to that a sense of savvy by some Aboriginal Art Centres, and organisations like Studio A, which recognise the name familiarity and visibility these prizes bring, and that entering art prizes is an essential part of the annual marketing strategy.

Making sense of the mosh

Every year, Archibald finalists deliver up another smorgasbord of the famous, and the not so famous, the quirky and the excessively hyperreal (no one really wants to be captured in that amount of detail, do they?), the earnest and the diverse.

When I first viewed the list of 2023 finalists online, ahead of this year’s announcement, I was somewhat scathing in my initial comments to self, typically bemoaning a fall in standard. But upon walking through the exhibition, it was not the standard, but rather the classification of artworks, that surprised me most.

For example, how do you read a totem-like sculpture of stacked letters spelling out ‘VOICE’ as an appropriate Wynne Prize entry, which states it is awarded to ‘the best landscape painting of Australian scenery in oils or watercolours or for the best example of figure sculpture by Australian artists’?

(Side note: is it just me, but isn’t a landscape painting and a figurative sculpture a bit like comparing apples and oranges?)

Similarly weird, the Sulman Prize pairs subject painting alongside genre painting. A bit closer than Wynne’s apples and oranges, but needlessly messy, and a questionable fit for 21st century considerations?

‘Genre painting developed particularly in Holland in the 17th century,’ explains the Tate. ‘The most typical subjects were scenes of peasant life or drinking in taverns, and tended to be small in scale.’ Yep, tick – still relevant topics of our day.

While both focus on depictions of the everyday, the Art Gallery of NSW (AGNSW) makes the point that a subject painting, in contrast to a genre painting, ‘is idealised or dramatised,’ using the tropes of poetry, religion, history or mythology.

Do you share my confusion, then, when Marikit Santiago’s The divine – a painting of the artist’s children – wins the Sulman in 2020, while an almost identical painting of herself and her children – Hallowed Be Thy Name (collaboration with Maella Santiago, Santi Mateo Santiago and Sarita Santiago) – is a finalist in this year’s Archibald? It feels like some weird graduation among categories.

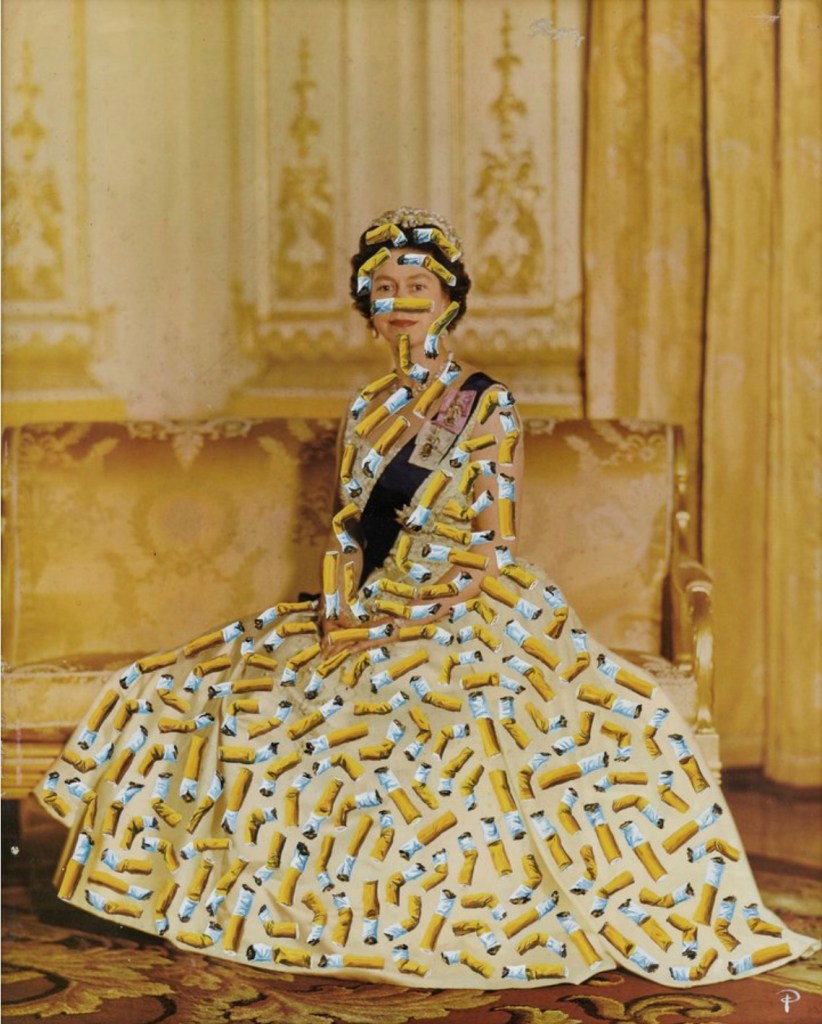

Or what about Philjames’ fantastic Ciggie-butt queen, which he describes as ‘essentially a still-life painting, as each butt is painted from life’, using a found vintage print of the late Queen Elizabeth II as his canvas.

It kind of wants to sit among the local royalty dished up by the Archibald Prize, which is awarded to the best portrait of ‘preferentially some man or woman distinguished in art, letters, science or politics’. The decider – it requires a live sitting (so that rules out Philjames’ piece).

Philjames says he is questioning art history and colonialism, calling his painting ‘a small act of rebellion’ and adding that, ‘sometimes we need to destroy in order to rebuild’.

So taking his cue, how do we need to destroy portraiture in order to rebuild it in our prize offerings?

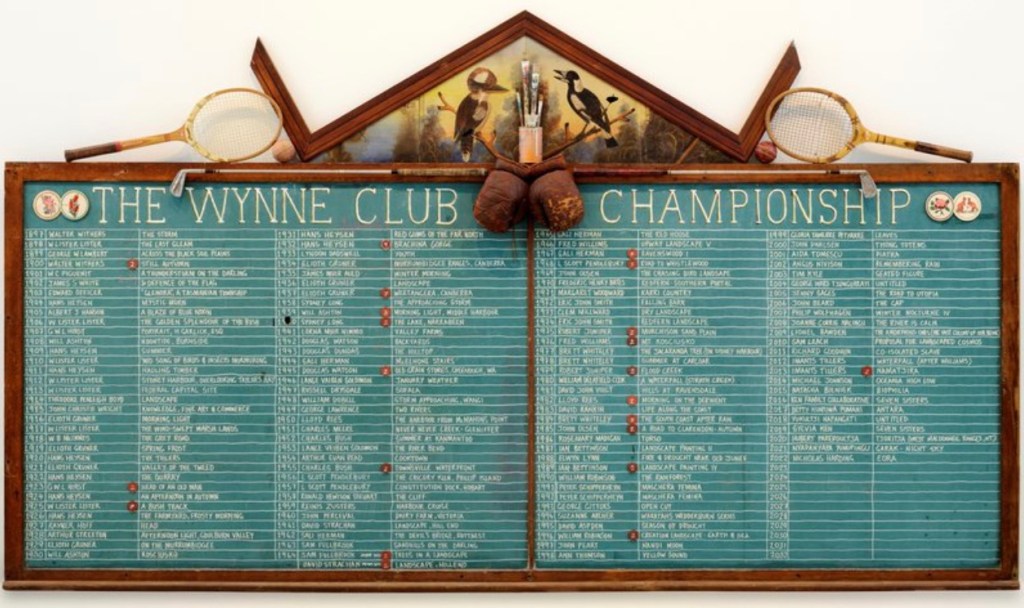

A wonderful piece of witty rebellion joining Philjames, came from James Powditch with his Wynne entry, The Wynne Club Championship. In it he draws an amusing comparison between the popularity of art prizes and Australia’s love of sport.

The 11-time finalist says: ‘I dwelt on why I felt compelled to enter the arena of the Wynne Prize again and again. Was it the joy of making a landscape? The thrill of competition? The glory of a win? And why did I put myself through this year after year? And [I thought of] all the others who have done the same for 127 years.’

Powditch decided to chalk up a conceptual landscape, listing the Wynne winners since 1897 on an old blackboard, using the honour board concept. He adds, ‘A notable detail is the sameness reflected in the winners’ names for much of the Prize’s history, reminding us how the demographic “landscape” of Australian art has recently evolved.’

Is Powditch pointing to the fact that his chances are slim if a betting man? The Wynne Prize has been awarded seven out of the last eight years to a First Nations artist (2016-2023), with the only hiatus being last year’s win by the late Nicholas Harding.

Like Philjames and Powditch, other artists are also testing the waters. Skidding back over the past 127 Wynne Prize winners since 1897, only 11 have been awarded to sculpture, with one of those arguably passing more as stalactite and a stalagmite forms (Lionel Bawden, 2009). The Wynne Prize pairs figurative sculpture alongside landscape painting. I have always found this a strange blurring.

Jump to: Postscript for the curious

The last time the Wynne Prize was awarded to a sculptural piece was in 2011 with Richard Goodwin’s Co-isolated slave, a reconfigured motorbike. And yet, this year figurative sculptures were received from Indigenous artists Billy Bain, Dinni Kunoth Kemarre and Hayley Panangka Coulthard, as well as Matthew Clarke, Pippin Drysdale, Clara Hali, James Powditch, Louis Pratt, and Michael Snape.

Particularly beautiful among the group is the suite of ceramic vessels from first-time finalist, Drysdale, which are every bit as dynamic and energised in their rhythms of land and country as Zaachariaha Fielding’s winning work Inma, which it happened to sit alongside.

A surprising 22% of this year’s Wynne finalists made sculptural works. Is there a sense of ‘it’s time’ driving entries? Sadly, I don’t think so. Australia remains entrenched in a landscape genre, one that remains tightly sutured to our sense of nationhood.

And, when it comes to landscape more generally as a genre, scale is a factor that swaggers influence over how we read a scene – are we drawn into it, immersed by it, consumed by its very ‘environment’? This sense of feeling your way through the contemporary landscape of art prizes today, is reiterated by the Archibald Prize.

Portraiture is about capturing that magical other. Sure, likeness helps, but without that zing of engagement, a portrait falls flat. It is not dissimilar to the energy an individual gives off. Call it vibes, call it personality – it is that magic that sits beyond the visage that makes us who we are. The Archi’s magic ingredient, then, is a perception of fame.

This is why exhibitions like Portrait23 are especially exciting in new thinking around the genre.

And, while Julia Gutman’s winning portrait, Head in the sky, feet on the ground, for some will not have that zing, it has that other Archibald quality – controversy.

It is the first time the Prize has been awarded to a textile-based artwork (which is great). It’s interesting that the selection comes after Portrait23 has been celebrated for its push across new medium use and definitions, including a number of textile commissions – which suggests a shift in zeitgeist. Gutman’s work also has an uncanny similarity of pose to Egon Schiele’s celebrated work Seated Woman with Bent Knees, which is unfortunate, but has seemingly skipped the gauntlet of critical commentary, so favoured around the Archi.

Read: Exhibition review Portrait23, NPG.

One can ponder that as prize genres, such as portraiture and landscape, become more complex pigeonholes in our times, more generalised and thematic art prizes are becoming an increasingly popular platform for artists to present their work, in a way that is perhaps more in sync with their broader practice.

Surely, we can all agree that is a positive development. Australians are not tiring of genre-led art prizes, indeed their popularity continues to grow. But so do audiences. They have been schooled now for 170-plus years, so are hungry for fresh and relevant narratives through these genres.

The finalists exhibition for the Archibald, Wynne and Sulman Prizes 2023 is at the Art Gallery of NSW until 3 September.

Portrait23: Identity remains on show at National Portrait Gallery, Canberra until 18 June 2023

The Lester Prize: Black Swan Years Retrospective is on show at Perth Town Hall until 20 May.

Postscript for the curious

The 11 sculptures that have won the Wynne Prize: Richard Goodwin Goodwin Co-isolated slave (2011), Lionel Baldwin The amorphous ones (the vast colony of our being)(2009), Tim Kyle Seated figure (2003), John Dahlsen Thong totems (2000), Peter Schipperheyn Maschera Maschio and Maschera Femina (double winner for 1991 and 1992), Rosemary Madigan Torso (1986), Lyndon Dadswell Youth (1933), Rayner Hoff Head (1927), G W L Hirst Head of an old man (1923), G W L Hirst Portrait, H Garlick, Esq (1907) and James S White In defence of the flag (1902), which is arguably a public memorial.