A recent ArtsHub essay critical of the Beijing Realism exhibition accuses us, its curators, of falling short in our curatorial responsibilities, especially to Chinese audiences. It does this by citing anonymous Chinese students who argue that the exhibition presents ‘narrow and unhelpful cultural stereotypes’ and ‘simplified cultural portrayals’.

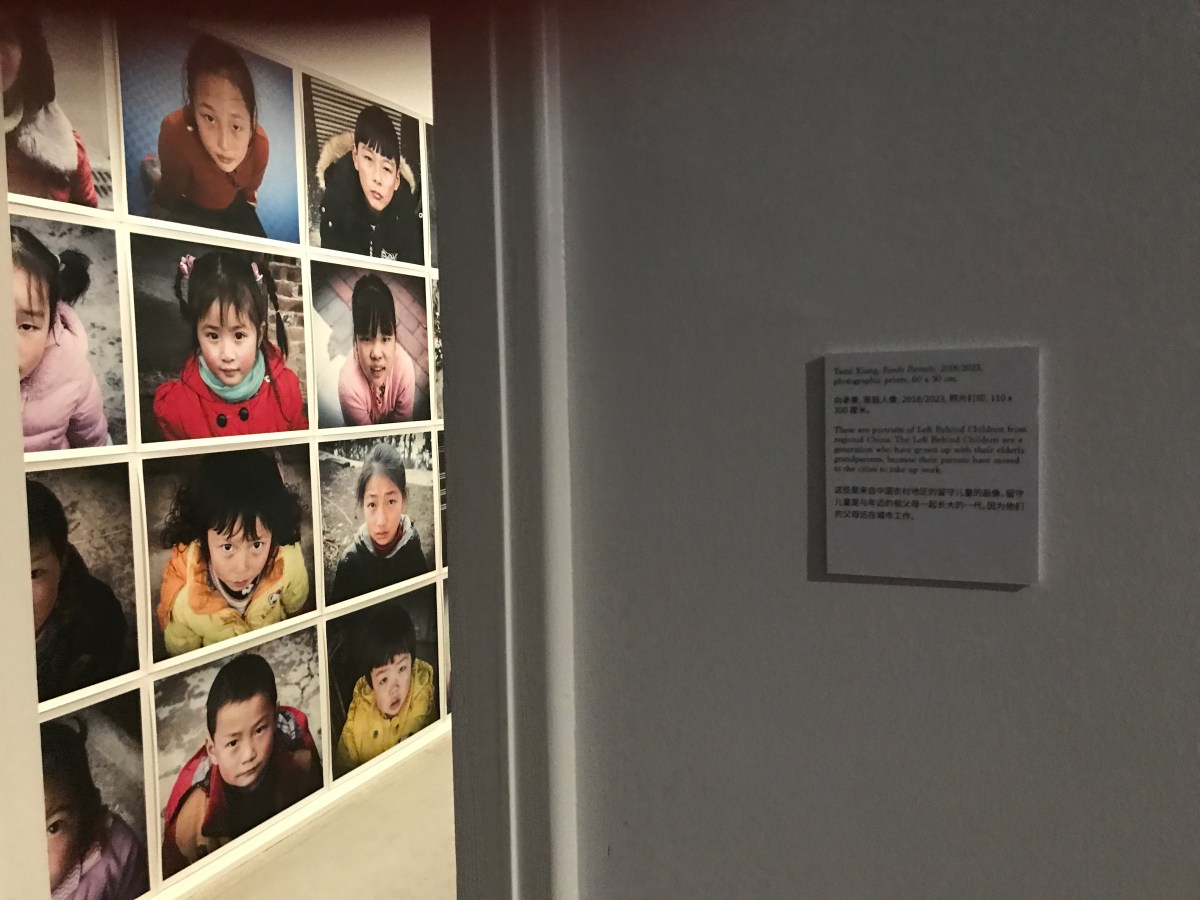

The work of one of us, Tami Xiang, was a particular target of their critique. Tami is also an artist in the show, with Lucky88 hanging as several silk prints from the ceiling in the middle of the main gallery space. The silks have portraits of Chinese pensioners printed on them, each holding different purchases from their local shop. The work involved Tami giving each of them 88 yuan to spend, the amount of their monthly pension. One of the photographs is of Tami’s mother, and others are of her old neighbours in China. The work documents the life Tami may have lived if she hadn’t left her village in the Chongqing district.

Tami’s silks hang in a space with other photographs and video work, including Hu Xiangqian’s Speech at the Edge of the World (2013). In this work too the artist returns to his home village. Hu gives a motivational speech to the students at his former primary school, where they appear bored and bemused. Such speeches take place at the beginning of the school day across China, and Hu always imagined giving one.

Lucky88 and Speech at the Edge of the World belong to the 21st century movement of socially engaged art and, like much of this type of art, it is uncomfortable to witness. These two artists are now out of place in their home town. The children in their school uniforms offer Hu no sense in which his speech about escaping their lives in the village is getting through. Other works we chose for this exhibition also inhabit this liminal zone, including Li Xiaofei’s videos of people working in Chinese factories, their faces drained by long hours performing mundane chores.

Was the show lacking a ‘curatorial ethics’ as Pickup and Lei argue? There has been a turn toward the ethics of representation in the 21st century, in which artists stand in for their communities, whether these communities be national, religious, Indigenous or ethnic. In this sense it would be seen as unethical for Darren, the co-curator of the show, to make work like Lucky88 or Speech at the Edge of the World, because he is not Chinese. In designing the show, there was a sense in which it may be unethical to name him as a curator at all, because of his background.

This ethics of representation means that today the most successful Australian artists internationally are Aboriginal artists who are critical of Australia. Richard Bell’s Pay the Rent (2022), for example, was the most prominent artwork at documenta 15 in 2022, and it counted the amount of money the Australian Government owes Aboriginal people for occupying Aboriginal land.

Is there, conversely, room in Australia for artists and artwork that is critical of the Chinese Government and society? Most Chinese art exhibited in Australia hides this critique, but our feeling is that photography and video are more confronting than other mediums. They are, as the title of our exhibition has it, ‘realism’ as they represent, with the illusion of the objective gaze, the lives of peasant and working class people. They hold within themselves the complexity of social conditions by which their portraits have come into being. The discomfort that they offer is precisely the sense of this complexity. It is worth noting that while the artists of Beijing Realism come from peasant and working class backgrounds, Chinese students in Australia are typically from the cities, and represent other parts of China.

Read: Australia must invest in First Nations curators and artists

The term ‘realism’ is out of place in the 21st century. After postmodernism and post-truth, it is difficult to argue seriously for the term. Historically, however, it has described a kind of ethics of representation. From Manet to Warhol, realist artists configured simple images to convey complex social realities. It not for us as curators to say that Beijing Realism was a good or bad exhibition, but we are encouraged to find that the show was uncomfortable, because this is a precise description of the kind of work that was on show.