For this show at the McClelland Sculpture Park and Gallery, a handful of works by five artists have been selected from a collection of over 2500, held together by the thread of exploring the Anthropocene. However, visiting an exhibition titled The McClelland Collection, this reviewer couldn’t help but question whether something went askew during the curatorial process.

Arguably it set up an unreasonable expectation of delving into McClelland’s vast permanent holding. But even if the goal was to invite viewers to dwell and carefully consider each work, the exhibition, located in two un-adjoining galleries, feels disorientating.

Sam Jinks’ hyper-realistic figure, The Hanging Man (2005) and Andrew Browne’s series of photographs and paintings are located in the side gallery next to the main exhibition entrance, easily missed without clear signage.

Jinks’ sculpture is exceptional in its own right, but it sits awkwardly between Browne’s works, separating the paintings from the photographic series – The Hanging Man is literally left suspended in context.

It’s also questionable as to why a content warning is not offered for the nude and goosebump-inducing figure, especially considering McClelland is so well-attended by families.

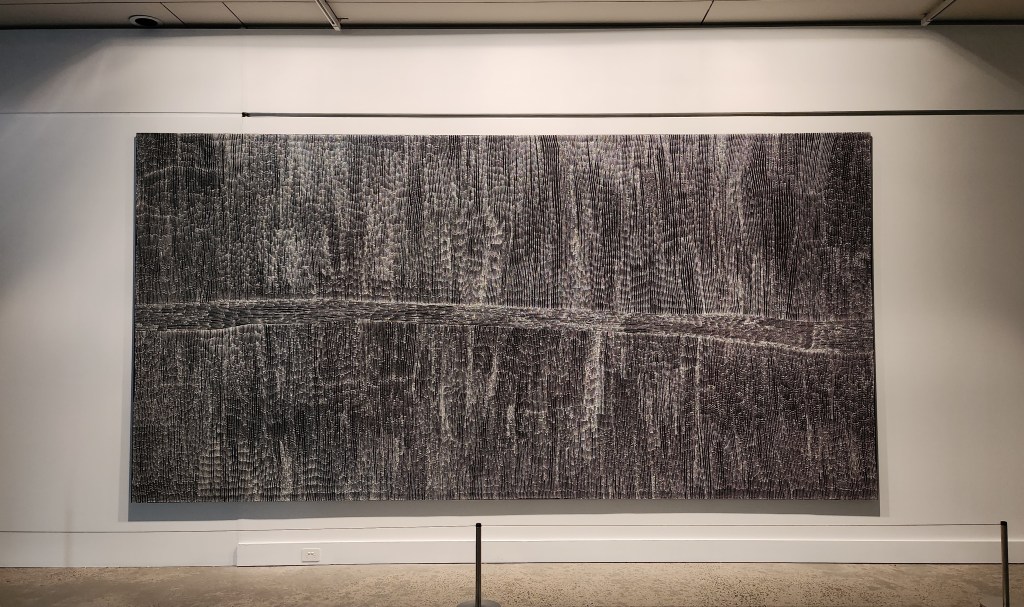

However, credit is due to the five artists, whose practices show deep engagement, research and thinking. Dorothy Napangardi’s sublime painting and Amias Hanley’s sound installation SUNKLAND (2021) tie together seamlessly, creating an environment where what is painted is now experienced, and what is heard can be seen.

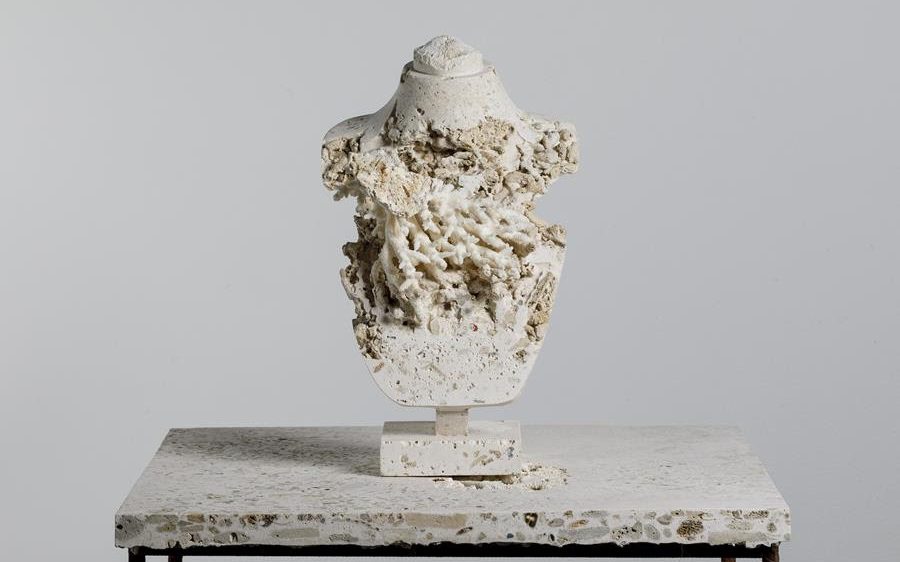

Nicholas Mangan’s Core-Coralations (2021) is most tightly knitted with commentary on ‘the destructive impact of human civilisation’. The decaying, headless bust has been created from fragments of coral jewellery, bringing to light the direct impact of the Great Barrier Reef’s coral bleaching.

A Victorian funerary bust of unknown creator and period is offered in comparison, a copy resembling the work of Italian artist Raffaelle Monti (1818-1881).

While an intricately crafted historic piece, linking it into the context of this exhibition feels rather stretched and unnecessary. It may have been better replaced with Jinks’ sculpture, leaving Browne’s works more breathing room in the separate gallery, which engages directly with McClelland’s site and landscape.

Read: Exhibition review: 100 faces, Museum of Australian Photography

While The McClelland Collection feels sparse compared to what was promised, individual works highlight critical practices from prominent Australian artists. Getting the most out of this show requires viewers to put aside their expectations around the expanse of the exhibition based on its title.

The McClelland Collection is on view at McClelland Gallery until 17 July.