Interdisciplinary artist of Japanese and Sāmoan descent, Yuki Kihara, was a bold choice for Aotearoa New Zealand’s pavilion at last year’s 59th Venice Biennale. A proud Fa’afafine woman (Sāmoa’s ‘third gender’), Kihara makes work that ‘interrogates and dismantles gender roles, (mis)representation and colonial legacies in the Pacific,’ explains curator Professor Natalie King OAM.

Kihara’s exhibition Paradise Camp caught the attention of international media, but how does it translate here? Co-commissioned by Powerhouse and Creative New Zealand, it opened this week in Australia.

Powerhouse is a very different venue than a Venice pavilion, and while both are weighted with layered histories, Kihara has used the Powerhouse Collection as a springboard to reinterpreting, and representing this installation.

The gallery space has been treated as a multilayered installation experience – the floor has a vinyl covering mimicking lapping tropical waters, and the walls are papered with a classic tourist-brochure style tropical scene. However, something is amiss here. The waterline sits waist-high to the viewer and the ‘tropical scene’ is in fact a shoreline impacted by rising sea levels from climate change, with a submerged dead forest beneath those crystalline waters.

Gazing around the space, this device of unravelling perceptions and history washes over you in layers, not unlike a tide – slowly, but with a powerful impact. The very title of Kihara’s work is a trigger – the two words ‘Paradise’ and ‘Camp’ are each loaded with gender and colonial associations.

Using the popularist anchor of Post-Impressionist artist Paul Gauguin’s Tahitian paintings, Kihara posits a case whether these were indeed painted in Tahiti. The artist moved there in 1891, drawn by its exotic ideal, only to find it had been ‘spoiled’ by commercialism.

This is played out, literally, as Kihara takes on the persona of Gauguin in the video work First Impressions: Paul Gauguin, a five-part talk show series where Kihara dons prosthetics in an attempt to not only ‘understand’ Gauguin, but also to ‘out’ him for his inappropriate appropriation.

The videos – a kooky mash-up with Fa’afafine witty comments on select Gauguin paintings – are also heartfelt and humorous, and at times celebrate a bitchy camp rhetoric.

While in its Venice presentation the video was presented on a floating screen at scale, at the Powerhouse it is embedded deeper into the exhibition space and more modestly presented.

The emphasis is placed, rather, on new work made by Kihara during a Powerhouse residency, which delves into the collection of 2900 glass plate negatives by 19th century Australian photographer Charles Kerry. It is a blatant ‘look, see’ moment to pull back and ground the bigger conversation.

They work beautifully with, and sit adjacent to, Kihara’s series Gauguin Landscapes, 2023, which splice photographs as ‘evidence’ with Gauguin’s paintings (recreated by Kihara), and are arranged so that the natural elements and lines in the Sāmoan landscape connect across the two. This is smart art making.

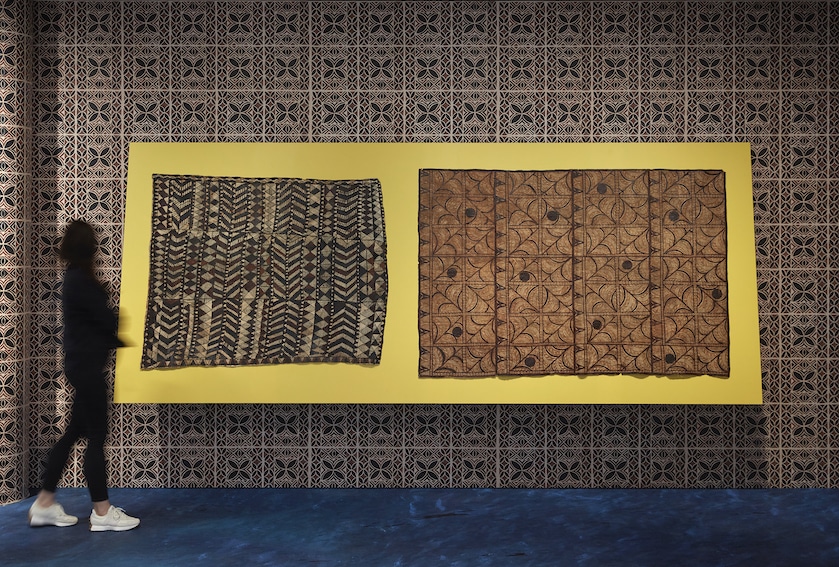

Also drawing on the Powerhouse Collection are three Siapo (Sāmoan bark cloths) that are punched into visual engagement on insanely bright canary yellow wall plinths, while backed by a wallpaper that pulls out, and repeats, their iconic decoration across the gallery.

Slightly less successful is Kihara’s Vārchive – a term the artist coined that uses the Sāmoan concept of Vā to describe Kihara’s relationship with her archive of research. Its overtly scrapbook feel – while it adds foundation to the narrative element of the show and builds context to Kihara’s research – reads a little clunky. The tableau of information attempts to ‘school’ the viewer, but ends up feeling more voyeuristic.

While one may question its production refinement in terms of ‘exhibition aesthetics’, one can be more forgiving in a museum context, where it arguably works on a more conceptual level contesting the authority of the museum as ‘history’ maker.

This further makes sense, given that central to the gallery is an area that Kihara intends for public programming to be embedded to further flesh out the topics she raises in the exhibition.

Unmistakably, the highlight of this exhibition (and what drew 485,079 visitors to Kihara’s Venice presentation of Paradise Camp) are her photographs that recreate Gauguin’s Tahitian paintings with the Fa’afafine community. Twelve images in total, they recast colonial narratives, patriarchal structures and Western misconceptions of the Pacific, in what Kihara describes as ‘upcycling Gauguin’.

While intersectionality rings out across this exhibition with a loud and proud voice, so too does a more urgent conversation of small island ecologies and environmental crises. As the light is captured on the vinyl wall transfers when entering the space, it almost seems that the water actually fills the gallery. There is a soft vulnerability that it captures, but also that initial impact of colour across this exhibition captures a deep celebration of community, of life and resilience. I think it will remain one of those benchmark exhibitions.

Paradise Camp by Yuki Kihara

Curated by Professor Natalie King OAM

Powerhouse Ultimo

24 March 2023 – December 2023

Free, no registration required.

Paradise Fair – 15 June 2023 – Yuki Kihara and Matavai Pacific Cultural Arts present a curated Pasifika program featuring dance, music and talks. Presented by Powerhouse Late and VIVID.

In August she will reveal a further work, in collaboration with with Harold Samu from the Sydney drag community.