In the summer of 2023, the quiet that typifies the beginning of the art year in Queensland is being disrupted by a cool critique that fractures the lens held by many Australians. Destiny Disrupted, like the book from which the exhibition takes its title, offers a powerful perspective on public affairs.

The seminal text by prominent Afghan American author Tamim Ansary, which was written in the wake of 9/11, revises the canon of Western history. Nur Shkembi has curated Destiny Disrupted

in her capacity as an independent curator and brings forth a chorus of voices that challenges salient narratives in contemporary Australian culture.

Although the artists each have an affiliation with Muslim-majority nations, references to the myriad of Islamic beliefs held in the cohort are sparing and nuanced, if not absent. Yet an unworldly reverence may be observed in this collection of artworks that appear to transcend time, tongue and the material.

Among the first artworks audiences encounter is Do Not Rush (2017), a poem by second generation Australian artist, born to Lebanese and Turkish migrants, Omar J Sakr. Written in English in the first person and directly addressing readers, this contemplation on colossal and callous destruction in the Middle East at the hands of US forces appears to scroll onto the museum floor like the opening text of a Star Wars film. The words include, ‘26,171 bombs on brown bodies, on our trees and animals and homes’.

A similarly timeless testimony is offered by Afghan-born artist Elyas Alavi through a line of his poetry in neon script ‘هل0 طعمها الدم’. The translation of the words and title of the artwork, Doesn’t it taste of blood? (2020), is appropriated from his own poetry. His witnessing of their application as graffiti in Iran ‘during a period of civil unrest’ was the inspiration for the installation. The preceding lines of the poem, as translated to English, include, ‘As you draw water from the well and make tea…’

In both artworks, the deployment of text as media imbues a sense of disembodiment to the affectingly explicit material, a spirituality born of extrication from the material in the former, and symbolically engaging electrical lighting as ephemera in the latter. This implication of what may remain post-apocalypse was similarly investigated using neon through the Philip K Dick inspired Blade Runner films. Both artists speak for the disruption of destinies through death, dispossession and displacement.

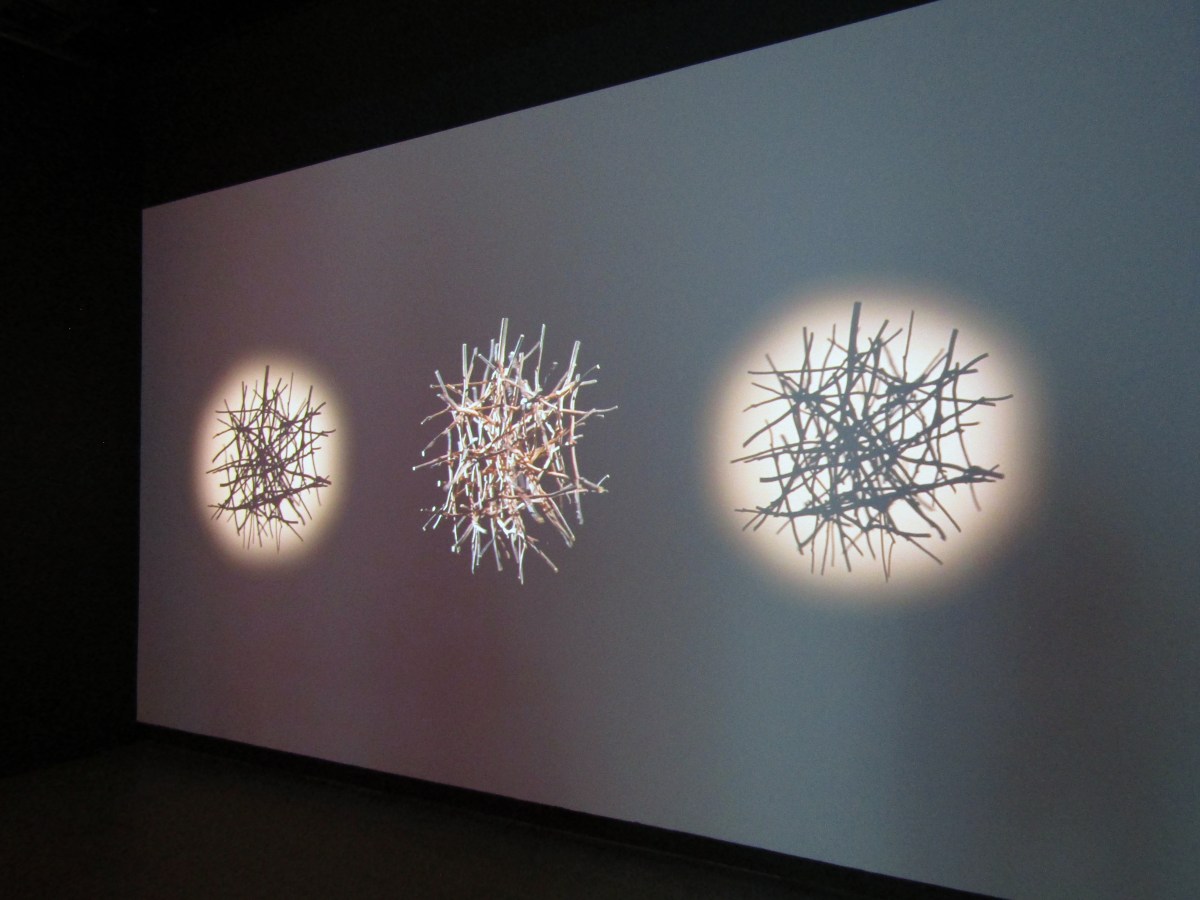

The continuum of material transformation from authentic to artifice, one that can strangely imply a similar spiritual transaction, also appears in both the films and in this exhibition. Not unlike the dead tree and hand-carved wooden horse in Blade Runner 2049, Hossein and Nassiem Valamanesh’s What goes around (2021) depicts branches from a fallen eucalyptus tree that was collected and filmed by the father and son collaboration.

The visual of the raw material, ‘bundle[d]’ to resemble a ‘biological’ molecule, rotating in digital space is married with audio of construction in the form of sawing and grinding. The layering of sounds played on a setar, a stringed instrument that originates from Hossein’s homeland of Iran, situates the narrative in a migration context.

The remnants of the tree appear ready for repurposing as fuel for a fire or scaffold for shelter. The artwork is celebratory of the reliance and resourcefulness of recent arrivals to this country. Extending beyond the injection of intellectual capital this community has offered our nation, their contribution through manual labour is also reflected upon in this diverse showcase.

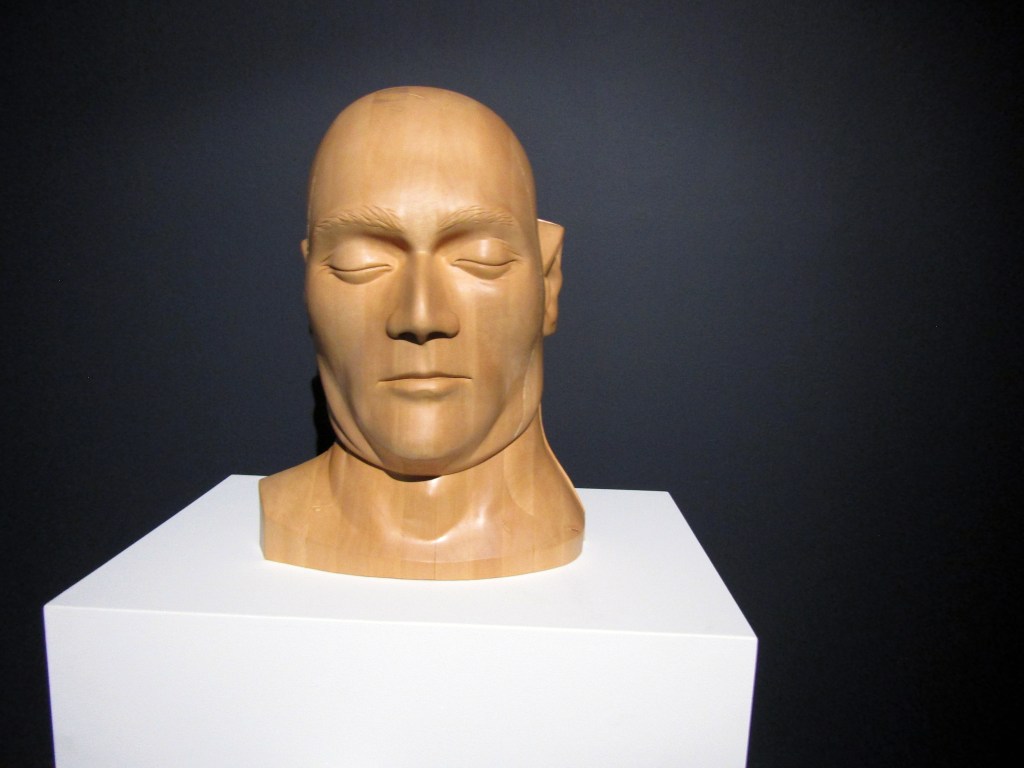

The installations of Australian artist Abdul-Rahman Abdullah reveal a culmination of critical conceptual rigour and consummate craftsmanship. Mask (After Ned Kelly) (2019) is a hyperreal wooden rendition of the iconoclast. The artist investigates the posthumous celebration of this Irish Catholic, who was convicted for murder yet venerated for opposing ‘corrupt’ British colonialists.

By whom and by what criteria are the deceased demonised or deified? This inclusion remains a peculiar selection for its scale, which required the bust to be carved in sections. However, the joins serve to emphasise the skill of the artist who hand-carved Kelly’s likeness from photographs of a cast made shortly after his execution.

The quasi-functional copper vessels by Australian artist with Lebanese heritage, Shireen Taweel, contribute to the hallowed atmosphere of this exhibition. She aptly applied repoussé and engraving, techniques acquired from artisans in Turkey, to create Devices for Seeing (2022). Through these cylindrical forms a history of seafaring is contemplated, dating back to a time when deference to the heavens extended beyond the wind, rain and tides, to the stars by which the sailors would navigate.

Read: Theatre review: Amadeus, Sydney Opera House

The ferrying of asylum seekers may be considered a contemporary legacy. The objects are an explicit reflection upon nautical navigation. However, the practice of scrying for destinies in the sky is also implied through this artwork.

Destiny Disrupted invites audiences to consider a different lens, one that challenges many cultural constructs to which they have grown accustomed. The counter-narratives offer the perspective of diaspora: insights into why some were required to relocate, the resilience with which they resumed their lives, and what they brought with them.

The exhibition highlights these contributions of mind, materials and manual labour. Disruption catalysed their departure from their homelands and characterised their arrival in their new home. These artworks are a powerful reminder of what can be achieved with the suspension of expectation.

This significant survey of artists who share a connection with Muslim-majority nations also includes contributions by Abdul Abdullah, Hoda Afshar, Safdar Ahmed, Phillip George and Khaled Sabsabi.

Destiny Disrupted

Griffith University Art Museum

Destiny Disrupted will be on display at the Griffith University Art Museum until 25 March 2023.