J.M.W. Turner, Constable, Monet and Pissarro – they are not names we would normally associate with ACMI, Australia’s national centre for the moving image. And yet, they are some of the stars of its recent exhibition, Light: Works from Tate’s Collection, which opened this week as part of the Melbourne Winter Masterpieces series.

Rather than corralling light artworks, it detours from the winter trend of illuminations and projections as an event per se, by unpacking light itself as a phenomena and a subject.

Take Monet – he and his other 19th century buddies embraced the en plein air (aka outdoors) painting of ‘light’ while bathing themselves in it. Is it so different to the kind of wash of light we feel when standing in a James Turrell light room, our eyes acutely seeking out detail, form and emotion?

Or how about the sinewy thread that connects light, architecture and the cinematic frame? Consider the echoed observations of artificial light in David Batchelor‘s tower of stacked, illuminated forms, Spectrum of Brick Lane 2 (2007) that greets audiences as they enter the gallery, with Ridley Scott’s film Blade Runner (1982), a gyrating, blinking future metropolis defined by light.

Batchelor’s tower was inspired by a bustling lane in London renowned for its South Asian restaurants, its stacked neon and flashing signs having a ‘future noir’ feel.

In many ways, the curators of this exhibition – like Ridley Scott – ask ‘How does light make us human?’ It is the very thesis of Turner’s massive painting The Deluge, which dominates the first gallery – a biblical tale of suffering in the face of an epic flood (sound familiar?). Within it, a black man rescues a drowning white woman (at a time when slavery was prominent). Rays of light cut through the scene in a tale of illumination where good wins over darkness. You can’t get more Hollywood than that.

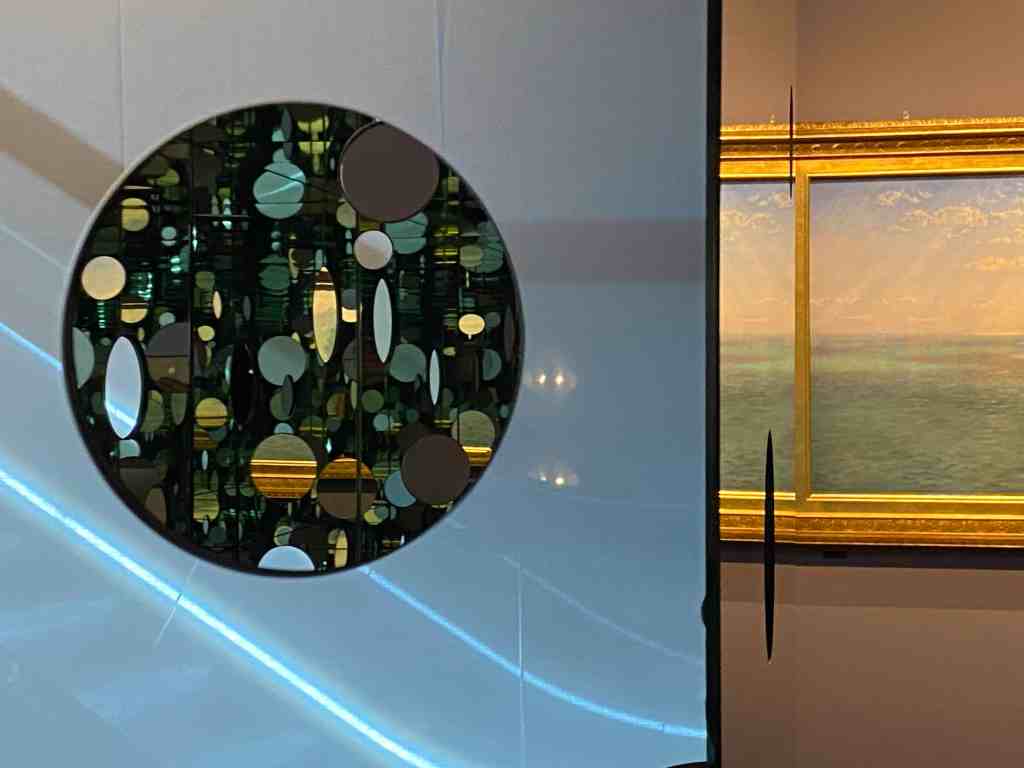

The Deluge is shown alongside no less than nine other paintings by Turner, the master of light. In each, light seemingly perforates the paintings’ murky surface, sucking you into its vortex. Among them is a suite of lecture diagrams c.1810 that demonstrate reflected light on polished metal globes or orbs. It is a form picked up in the next gallery with Liliane Lijin’s kinetic installation, Liquid Reflections (1968) where, like Turner, she uses the orb as a receptacle to play out the physics of light and matter.

Lijin’s ‘aim was to capture light and “keep it alive” within a sculpture,’ writes Kate Warren in an essay accompanying the exhibition, adding, ‘without light, there would be no film, no photography, no cinema.’

Working with ACMI, Tate has curated this compact show to mess with our expectations and pique our curiosity. It is not dominated by the moving image; rather it takes filmic cues and then steps back ‘into the light’ with a push and pull across time, technology and experimentation.

It breathes like an accordion, both fluid and yet defining a trajectory – a journey through light presented as a collection of rooms linked by illuminated arches. The walls are muted in colour, and the lighting is low, making the artworks appear to be illuminated within. It is almost cinematic in its theatricality.

It is a tone charged from the outset: in the first gallery, visitors are faced with two themes as disparate as they come: scientific light and spiritual light. Later in the exhibition it is the pairing of pictograms, film and architecture – persistently pairing and pushing.

A good example is the pairing of painters Vilhelm Hammershøi and William Rothenstein, who flesh out narratives of interior light through banal scenes, with a carpet (yes the very floor one walks across) by Philippe Parreno, titled 6.00 PM (2000-2006).

One could be forgiven for confusing it with shadows cast by the architecture around them. What I love about this work in this context is its filmic quality – it locates the viewer within a mise en scene narrated by light.

This punchy play and head thwack is continued in the next room, where a work by Yayoi Kusama is paired with paintings by Monet, Brett, Sisley and Pissarro – an insanely whacky pairing on first consideration. But positioning oneself to visually ‘fall’ into her infinity mirrored cube of floating discs, The Passing Winter (2005), it is easy to connect with the dabbled light of Monet or Pissarro – pixelation or fracturing of light on a surface.

Further, there is a oblique connection here to cinematic history via Thomas Edison’s Kinetoscope (1893), a pre-cinematic device that presented moving images via a ‘peephole’, designed to be viewed by one person at a time.

The more you throw yourself into the viewing experience at ACMI, the more you get out of this exhibition.

This is best played out in the belly of this exhibition, where a distinct shift in tone is evident – one moves from the phenomenal as depicted to the phenomenal as experienced.

A highlight is the tiny 16mm film by Bauhaus artist László Moholy-Nagy from 1930, LICHTSPIEL SCHWARZ-WEISS- GRAU, which extend his photograms (images created by objects on light sensitive paper) into a moving image.

Moholy-Nagy was among the European avant-garde working at the outbreak of WWI, artists who rejected the opulence of a past world view. It was also the time when German expressionist cinema flourished and stark contrasts of dark and light (like the photogram) were aesthetics heightened as narrative in themselves.

Read: Exhibition review: Land Abounds, Ngununggula

Perhaps the most famous such works is Fritz Lang’s film Metropolis (1927), a new world view of New York’s skyline. ‘It was 1933, when Hitler was appointed chancellor and Lang was one of the most celebrated directors in the country. By 1934, he would be making movies in Hollywood,’ explains ACMI.

This is a thread that carries from that first work by Batchelor at the entrance of Light, through to Moholy-Nagy and on to Dan Flavin’s ‘monument’ for V. Tatlin (1966-1969) – a sculpture of white fluorescent light tubes that pay homage to the Russian Constructivist Tatlin. All are steeped in ideals of utopian urbanisation played out through light, and an embrace of a cusp of the new.

Flavin’s name is inseparable from the light art movement, connected with the use of readily available fluorescent tubes in the 1960s. It described a new sculptural space articulated by light.

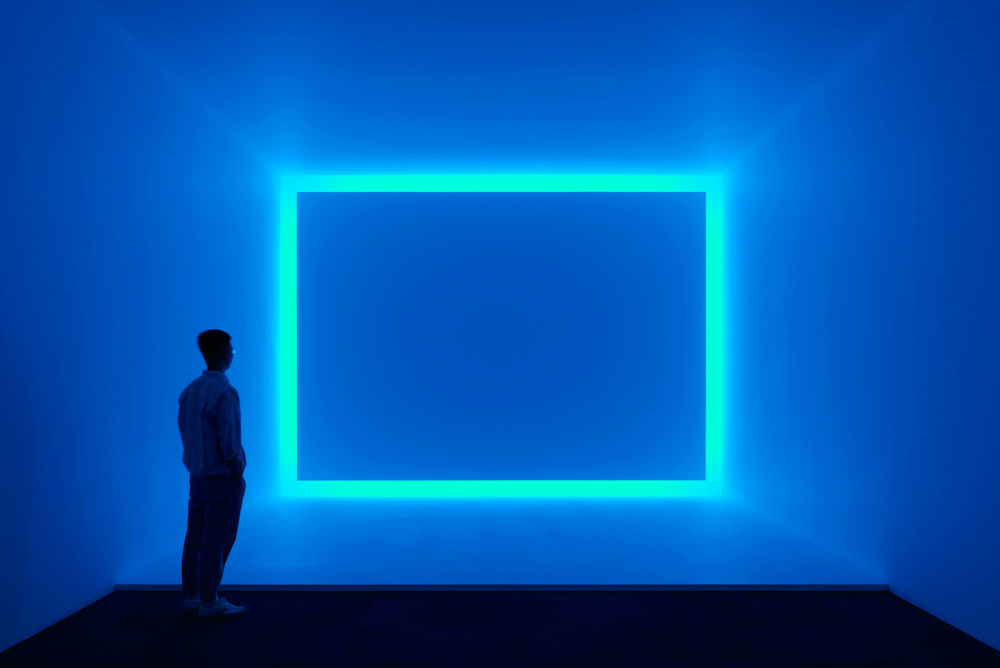

You can’t mention Flavin without James Turrell, and the later Olafur Eliasson – all three clustered here for this exhibition. Collectively, they have used light to upend our perceptions, altering our understanding of architecture and our spatial relationship with the world. Essentially, their work often take us to another dimension, out of ourselves – not unlike film.

Light fans will not be disappointed by Turrell’s Raemar, Blue 1969 (one of his earliest, and the show would have been flat without it). Standing with it, one’s retina starts to burn with the imprint of its blue keyline; the work is less about the immense sea of blue in the room, and more about the hovering form created by light – where the intangible replaces the tangible.

It is this suspension of belief – and an encouragement of our embrace of it – that I think is the underlying focus of this exhibition. In short, Light Works from Tate’s Collection pushes you around – mentally – like a rag doll, wowed by epic encounters with a roll call of masters then mashed up with curiosity that leaves you falling into aesthetic disjunctures, before being pulled back by curatorial smarts that join the dots across time.

Light: Works from Tate’s Collection is showing at ACMI from 16 June – 13 November 2022. The exhibition is exclusive to ACMI.

Ticketed: Full $30, Concession $27, Member $25, Child $10, Family $70.

The writer travelled as a guest of ACMI.