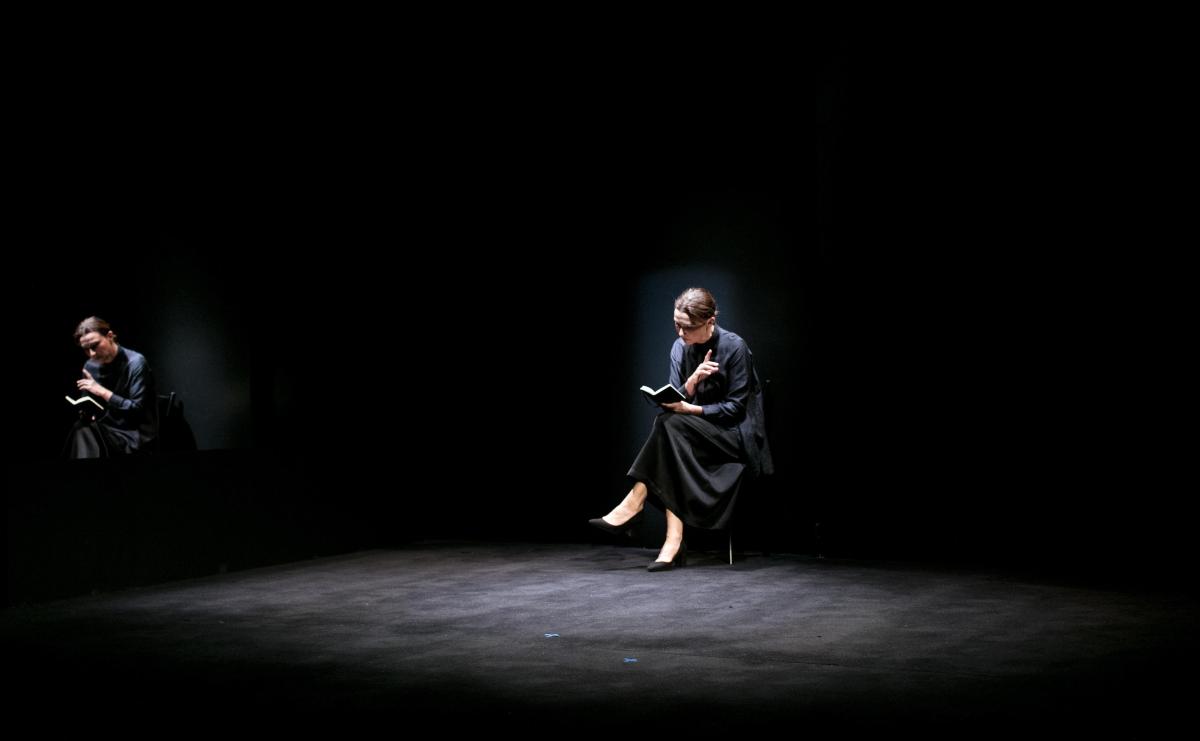

Virginia Woolf’s 1928 lecture, given to students at the University of Cambridge in the UK, has been adapted for the stage many times. This Belvoir production, however, cleverly and concisely brings the essay into the 21st century. The set is claustrophobic and dingy, a dark space metaphorically as well as literally. A single black chair sits in a murky spotlight centre-stage. Behind is a large square mirror, perhaps 3m by 3m, which reflects the audience. The effect is to cunningly include us in the drama as the student recipients of Woolf’s lecture.

Woolf is played by Anita Hegh with a droll and confident sense of purpose. Dressed in a drab, shapeless, muted grey two-piece smock, she begins by describing the contrasting experience of the male and female dining halls of the university. While the male dons enjoy fine meals and erudite conversation, washed down with fine wines and port, dinner at the solitary women’s college, red brick and devoid of the wealthy generations of benefactors which supported the male institutions, is an overbaked affair of transparent soup, leathered beef, curled sprouts and dry crackers served with water.

The effect of the disparity of money and opportunity extends beyond the dining halls, Woolf argues, to the wealth of the mind and the creation of literature. Few women have had the ‘dignity of luxury, privacy and space,’ offered to the opposite sex in the nearby cossetted cloisters. Consequently, their story has been predominantly told through and by male authors, keener for female characters to be looking glasses their own egos than true reflections of the female spirit. Historically, the few women with the means and time to write were limited to creating dramas which unfolded in the living rooms they were restricted to existing in.

Woolf is patently exasperated by this state of affairs, but the Belvoir audience are not allowed to wallow in anger and self-pity. The tightly scripted adaptation by Carissa Licciardello and Tom Wright is both intellectually rigorous and challenging. The script and the direction (also by Licciardello) boldly and intelligently create a depth of storytelling that goes much deeper than Woolf’s text. The mirror at the back of the stage is revealed to be two-way, and behind it sits an androgynous being (Ella Prince), dressed like Woolf, but somehow different, listening to the lecture from an empty box-like room. A russet leaf falls and the being catches it. The leaf represents the lifeline Woolf herself was given, in the form of a legacy from a dying aunt, £500 a year for life, which allowed her the freedom to write. Over a series of vignettes, punctuating Woolf’s speech, the being gradually grows in independence, and finally emerges as a writer in a room of their own.

The final section of Woolf’s oration presents a clarion call to women to seize the opportunity to write, write anything, whether fiction or non-fiction, science, travel, biography. The tableaus eruditely and eloquently surmise the message that without an independent income and a room of one’s own, women will remain stifled and suppressed both creatively and as humans. However, this adaptation hints at something still deeper. The script, the staging, the costumes and set (David Fleischer) as well as subtle musical underscore (Alice Chance) create a symbiotic vision of what a world could be like if gender was somehow not relevant. As such, the play presents a reckoning, not just of the way gender has shaped the role and possibilities of women, but the exciting possibilities offered by gender neutrality.

4 ½ stars: ★★★★☆

A Room of One’s Own

Adapted for the Stage by Carissa Licciardello and Tom Wright

Directed by Carissa Licciardello

Set and Costume Designer: David Fleischer

Composer: Alice Chance

Sound Designer: Paul Charlier

Cast: Anita Hegh and Ella Prince

Belvoir Upstairs Theatre, Surry Hills

6-23 May 2021