This past week, the National Gallery of Australia (NGA) has hosted the Know My Name conference, which has charted ideas around feminism, decolonising the body, gendered curatorial bias and entrenched language.

As artist Sally Smart flatly stated on the first day: ‘Know My Name is about acreage; we have to take up space.’

But like the occupation of any space there are barriers, both historical and existing in a current time.

Part of the lens applied by this conference was to take a look at feminism and the representation of women, and female identifying artists in our institutions, in our history books, and in our futures.

Natasha Bullock, NGA Assistant Director Artistic Programs, described Know My Name as ‘a gender equity access plan’, adding that ‘we are pulling at the weeds.’

It was only fitting then, that esteemed British art historian and cultural analyst of international, postcolonial feminist studies, Griselda Pollock, join the conversation – after all, she could be described as one of the first to pull at those weeds.

Many of us still have a well-thumbed copy of her publication, Vision and Difference: [Femininity, Feminism, and Histories of Art], released in 1987 at a time when women artists were near invisible in the annuals of art history and the hallowed halls of our museums.

For more than two decades, she has challenged mainstream models that have excluded the role of women in art.

‘I didn’t do it on my own. Without the Women’s Movement I would have been some boring assistant in the back room of a bookshop. I was absolutely caught up in the tumult,’ said Pollock.

‘I wanted to be political in my own name, and with some kind of authenticity.’

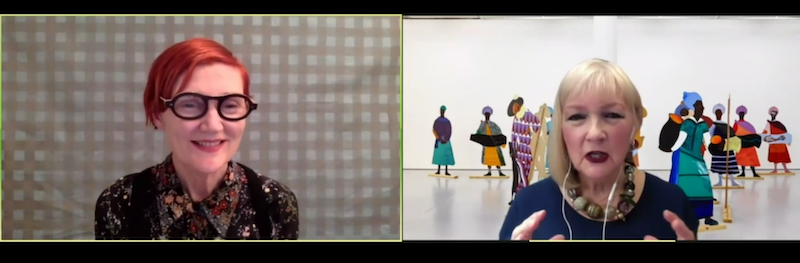

Griselda Pollock.

Pollock spoke of a time when Peggy Guggenheim arrived in New York in 1939 and visited the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) to find there was not a women artist in sight. ‘We don’t want to be called ‘the women’, we want to be in MoMA,’ she paraphrased Guggenheim.

‘The point was that women artists were everywhere … but the 20th century had become systematically exclusive,’ she added. Pollock said that while the curators, the critics and the historians of the day, knew who the women artists were, they did not select them.

‘This is not about being saved or recovered, it was about asking why they had been disappeared in their own lifetime,’ said Pollock.

Bullock added that the conference was intended as ‘a way to take an expansive approach.’

Artist Sally Smart and art historian Griselda Pollock in conversation via virtual NGA conference Know My Name.

BEYOND THE SILO OF GENDER

Artist Amrita Hepi performed a new work for the conference. She said: ‘If we are dealing within the realm of ideas, I would never start with thinking about labelling the identity of myself.’

‘If we are coming from the understanding that we are from multiple contexts, then it is not that gender becomes prevalent, but as artists we have the potential to pull away from that to the bigger things,’ said Hepi.

‘Gender is just one of the contexts I have to play with, rather than the thing that I am solely defined through.’

Amrita Hepi, artist.

Gender for Smart is really important. ‘It is a part of me, but it is also about a system and making it tidy. ‘We want to have that complexity. If it is just gender then it is problematic; if it’s just packaged up as that, then it denies so much more,’ Smart continued.

Worimi woman, curator, filmmaker, artist and academic Genevieve Grieves opened the conference with a paper discussing a First Nations’ perspectives on art, gender and feminism.

She believes that key to that equity aimed for, is acknowledging First Nations women into Australian feminist history. ‘A quarter of the NGA’s collection is by women artists, and Aboriginal and Torres Strait women are only a third of that collection,’ pointed out Grieves.

‘We need to be included in the cannon.’

Read: Decolonising Feminism: A First Nations perspective

Grieves said: ‘Once we get close to some equity, we will be able to think outside being a female making art, but there is still a huge amount of inequity, so we will still be women artists and marginalised in that way, and with that language.’

She added: ‘Institutions work in certain ways, and they are generally categorised.’

Pollock extended the argument: ‘I have come up against an imagined notion of the public, as it if it was not composed of complexity or difference and putting a little quarantine around art.

‘When we go to the gallery, we learn a foreign language. They will tell you why Picasso is great, but they will never ask, “What is this man doing? And Vemeer, what was he trying to see?” Art is itself a kind of investigation that requires the words to tease it out.’ She said that we are still struggling with the words to carve a place for women artists.

Smart added: ‘The structure has to be workable to unravel the structures that have been problematic.’

‘I never use women artist and I never say female it is a very heavy sound – think of David Attenborough’s lions and buffalos – so I have come up with artist men and artists women, said Pollock.

Pollock said that we are at a point in this journey of feminism when we are saying, “Hey wait a minute, we are not all the same.” ‘Gender still remains, regardless of what other groups emerge in our conversations – religious, racial, sexual, social – we are not intersectional. We are not sectors. We are all entangled in the multi-thread of this. How do we foster the psychological witness // w(h)itness – we need to be witness to the wrongs of the world but also stand “with”.’

‘It is something we have to absolutely, be totally conscious of, and take that consciousness into our art world and our institutions,’ said Smart. ‘We can let this time of change unravel all the momentum. It is a space we have to be very vigilant in.’

WORKING AGAINST AN ENTRENCHED SYSTEM

‘[At art school] we were given the words, we could see the images, but for female artists you weren’t written in there or given the authoritative voice – you were fighting all the time,’ Smart reflected on studying in the ’80s.

She described it as a systemic erasure through art history, that has become a kind of echo chamber across our institutions, critics, curators and the market. ‘It is a whole system,’ she said.

Read: 20×20: Sheilas in the art market – gender bias goes commercial

Pollock continued: ‘Without a financial value, the curators and the critics don’t pay attention. The whole thing is not to justify inclusion, [rather] it is to have the language that is appropriate to the nature of the artistic project, and also the recognition of difference.

‘Curators, as keepers or carriers of the story, were educated [in that mindset] and have created that [continuum]. And then curators follow the market – it is a circular movement – so unless you have a language to pierce through that, it will not change,’ Pollock said.

We are in a kind of cultural battle for the public to understand what they do not get to see.

Griselda Pollock

She said that having worked the world over and sat in on many curatorial meetings, her question, “What about women, what about more inclusivity?” was always answered with, “Well give us some names that have this level recognition and financial value”, and it is not there,’ Pollock said.

She continued: ‘I find curators in general afraid to step out of line – they constantly look to the left and to right – and if they step out, they just disappear.’

It was a view Smart picked up on, adding that there is no safe place for curators to do that, an that courage is little rewarded.

Smart questioned: ‘This conference talks about a lot of feminisms and what mean to a lot of different people. And, that memory will enable us to make a future. But how do we put all that into context now?’

Pollock answered: ‘In the 2015-8 period, there was an intense moment of writing – in these terms a second wave of feminism – and then a third wave, and a fourth wave. But this structure implies that we couldn’t live in overlapping time.

‘Women were almost impulsively killing their mothers … the urgencies of now aren’t answered by way of doing things in the past, and we are struggling with new questions. We don’t have the right to disown the past. Our history invests in names. Having a name – not in the sense of brand or marketable name – is a historical force that needs you to be understood,’ she added.

It is this very naming that is central to the Know My Name project, which has been a global phenomenon.

COMPLACENCY BREEDS INEQUITY

‘When the #metoo movement happened, like so many I was moved by it,’ said Dr Wendy Were, Executive Director, Advocacy and Development, Australia Council for the Arts, and who joined Smart in a panel discussion.

‘I have been sexually harassed and sexually assaulted; I have been underestimated, and underpaid … My daughters look at cultural artefacts and marvel at their cultural sexism – that is a sign of cultural progression, but we still have a long way to go,’ continued Were.

‘There is no room for complacency, when it comes to issues of social equity, especially against the turbulence of these times,’ Were said.

She said that research by the Council shows that Australian women have higher rates of cultural participation than men. ‘We get it! We know how important it is to our culture and our kids,’ Were said.

Despite high engagement, the gender pay gap persists. Artist are paid 25% less than overall workforce, which pays women 16% less than their male colleagues.

‘This is inexcusable and has nothing to do with talent,’ said Were.

Grieves added: ‘We are incredibly entangled in this country. It is an interesting thing to choose to share the differences and not share the similarities. My perspective is to embrace that entanglement and to understand who you are in realty to the challenges.’

The Know My Name conference was hosted by the National Gallery of Australia and was presented virtually, November 2020.