It’s just past 10 a.m. and my partner, on his third virtual meeting today, is working non-stop in our home office. My son has taken over the family room to attend a virtual science camp and video-editing classes and to play video games. I now realize that this will be his work space to attend distance learning classes in the fall.

For this reason, each morning, I find myself carrying my laptop and tea around my house trying to find a quiet place to work. Before the pandemic, I never needed a dedicated space at home for work. But now I’m faced with teaching online this fall and won’t have access to my campus office, which closed in March.

With Google announcing that its 200,000 employees can work from home until June 2021 – and Twitter, Square and Slack announcing that employees could still continue working remotely after the pandemic ends – I’m sure others find themselves in the same boat of not having their own dedicated professional workspace.

And as I explain in my recent book on the social history of the home office, historically, it’s been women who have been the ones left searching for space.

The emergence of the ‘chamber room’

To better understand the makeshift nature of workspaces in the home – and why the spaces are often gendered – it’s important to look at how the home office first emerged as a distinct space.

In the 18th century, three separate spheres of domestic activity started to appear in middle-class and wealthy single-family homes. There was a social area for hosting guests, such as dining and living rooms; a service zone, which included the kitchen, cellar and laundry areas; and a sleeping area, which was the most private part of the house.

What we now call the home office emerged from generically named “chamber” rooms used by both men and women prior to the 19th century. The majority of the chamber rooms were later simply labeled “bedrooms” on builders’ floor plans. However, beginning in the 19th century, some of these spaces depicted on floor plans were interchangeably referred to as the library, den or study.

By the late 19th century, the study became primarily a space reserved for male professionals to conduct business at home, indulge in scholarly pursuits and entertain friends. For example, clergy, merchants and doctors needed a study or “interview room” because their work was more likely to be conducted at home.

The study was often separated from the private zones of the house and placed as close to the front door as possible – in the home’s social zone – to maintain family privacy.

But then, in the early 20th century, the study largely disappeared from standard, middle-class homes, which were getting smaller, remaining only in houses built for upper-middle-class professionals, creative professionals and the wealthy.

Selling the idea of working from home

Even though the study was a male space for leisure and occasional work, the home was largely seen – and championed – as a place that fostered family life.

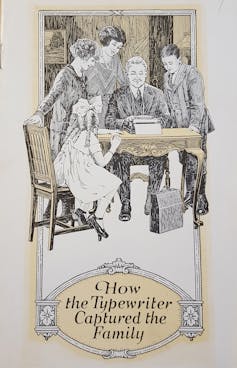

Yet companies that sold office supplies saw the home as an untapped market. All they needed to do was convince Americans that being able to work from home was a form of convenience. Through advertisements, these companies encouraged Americans to create distinct spaces for work that needed to be properly outfitted with office equipment.

For example, in 1921, Remington Rand began marketing portable typewriters, with advertisements that tried to sell consumers on the idea of flexibility and the ability to work in the comfort of one’s home. And in the 1950s, Bell Telephone teamed up with the builders of middle-class homes to market the installation of additional telephone lines as a way to combine work and leisure under one roof.

When PCs replaced typewriters, computer companies such as Apple and IBM geared their ads towards professionals, depicting their products as tools that would allow them to telecommute, run a business out of the home or make it easier for their kids to complete homework.

Separate but unequal spaces

As these technologies started appearing in more and more homes, families started to wonder where to put them.

Popular culture offered some models. In the sitcom “Leave It to Beaver,” the study of the father, Ward Cleaver, is equipped with bookshelves, a globe, two leather chairs, a desk and a telephone. It’s a place where Ward occasionally works from home in the evening and relaxes during the weekend.

By then, however, most middle-class homes lacked studies.

Furthermore, during the postwar period, typewriter and telephone companies didn’t just advertise their products to men. They also sought to entice middle-class women into using their products to better manage tasks like corresponding with schools, insurance brokers and doctors, as well as keeping family records and paying bills. However, unlike men, women’s workspaces in advertisements, newspapers and on television were often depicted as a planning desk in the kitchen or as a little desk in the master bedroom. Rarely, if ever, did they have their own space.

Where to put office equipment was another issue. Placing it in the master bedroom interfered with the perceived functions of the bedroom: intimacy and relaxation. A PC in the living room competed with the television, while office equipment in the kitchen or dining room impeded the ability to work uninterrupted by other family members. For these reasons, advertisements and computing magazines in the 1980s began to recommend new spaces dedicated exclusively to PCs, such as the home office or a “hobby room.”

The home office works well as a quiet room to concentrate and work, but in homes that do have one – and when both partners are at home, as is increasingly the case – that space often defaults to the man.

In the end, all those companies’ advertising dollars paid off. We were working from home in greater numbers before the pandemic, and the number has since risen as offices around the country shuttered. But we’re still stuck with the same issues of too much work and not enough space to do it – with women often getting the short end of the stick.![]()

Elizabeth Patton, Assistant Professor of Media and Communication Studies, University of Maryland, Baltimore County

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.