I have been thinking a lot lately of how many worlds there are contained in very small spaces and how every person is really one world to himself unconnected by anyone or any thing.

Joy Hester, 1947

So said artist Joy Hester, in words that were no doubt a response to dramatic life events that have overshadowed attempts at a sustained critical appreciation of her art.

In 1947, Hester famously left her husband and young son, Sweeney (who was later adopted by Sunday and John Reed) for artist and poet Gray Smith. She was also diagnosed with advanced Hodgkin’s Disease which was at that stage an incurable cancer.

Yet, her statement is striking for the fact that Hester’s entire body of work, her modus operandi, can be understood as an exploration of human relationships, connections, in all their complexity. A major survey exhibition at Heide now acknowledges this.

Joy Hester: Remember Me was postponed due to coronavirus lockdown but Heide reopened on 30 June. Image Heide.

Defiant from the start

Born in 1920 to middle-class parents in Melbourne, Hester defied convention from the outset and found a creative and intellectual home in her association with the Victorians Arts Society and at the Contemporary Arts Society in 1938. She joined a group of artists such as Arthur Boyd, Sidney Nolan, John Percival, Danila Vassilieff and Albert Tucker, whom she married in 1941.

She also met the Reeds, patrons of the arts who opened their home “Heide” to their artistic circle. The couple would become her lifelong supporters, friends and benefactors.

Joy Hester, John Reed with binoculars, Sunday Reed and Sidney Nolan holding Sweeney at the beach in 1945. Albert Tucker/State Library of Victoria

Like most Australian artists of the 1940s and 1950s, Hester’s work was a reflection of the huge shifts in Australian culture as it emerged from the violence of war into a definite crisis of national identity.

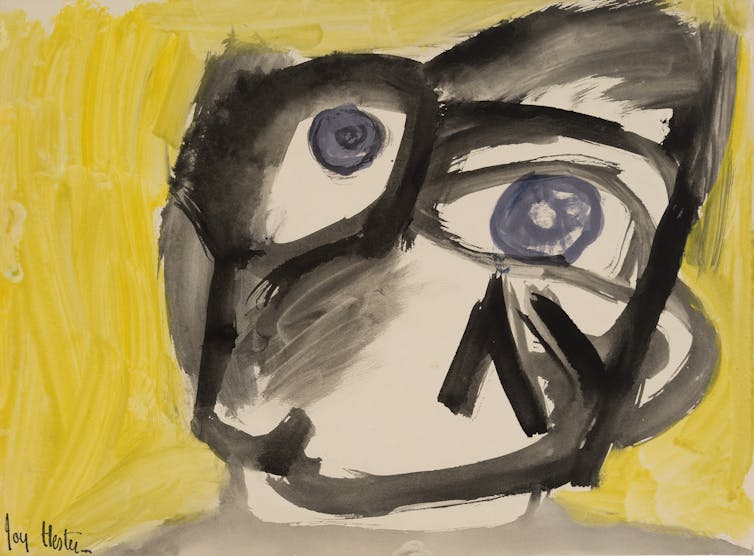

Influenced by European modernism, particularly the experiments in formalism by Picasso, the German expressionists and surrealism, Hester also uses the body, particularly the head and eyes, as a site for formal experimentation.

Yet unlike other artists of the day, male or female, Hester develops her own visual vocabulary to explore the intensity of feelings and relationships in an intimate, confronting way.

The simplicity of her mark-making in her predominantly pen and ink drawings, appears to be at odds with the often unflinching rawness of the images, leaving the viewer with a sense of uneasiness as to what they are actually witnessing in the work.

Rather than being autobiographical, the characters in her drawings are often amorphous, unidentifiable as her short career (a span of only 20 years) progresses. Hester sought to capture a moment in time that could be easily “felt” by the viewer.

The female body

The fact Hester’s work was focused on the topography of emotions, as well as female bodily experience, no doubt added to its lukewarm reception from male critics in her lifetime.

As Heide senior curator Kendrah Morgan points out in the exhibition catalogue, she was one of the very few Australian women artists to

explore female sexuality and do so in a way that neither celebrates the female nude nor eroticism per se, but rather interrogates the sensory and emotional conditions of deep connection and physical intimacy.

Hester often worked in series, creating different variations on the same theme.

Images from Nazi concentration camps, the writings of Jean Cocteau as he battled his history of addiction, a preoccupation with death, and the effects of her own radiation treatment all found their way into series of often harrowing works of suffering and loss.

The series Faces (1947-1948), was described by critic Barrett Reid in 1966 as revealing aspects of human identity at its “most masked and vulnerable, most exposed, when totally given to powerful emotion”.

Face (With Yellow Background), Joy Hester, circa 1947. Heide Museum of Modern Art/Barrett Reid.

Hester herself was disturbed by their intensity as she surveyed them on her wall referring to them as “frightening things” and almost immediately taking them down.

Searching for self

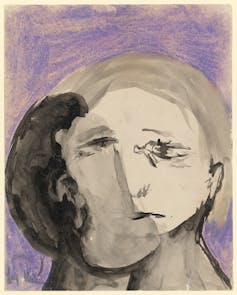

In the Love series (1947-49) we see the artist exploring the complexity of sexual relationships in terms of connection and separateness.

Much of Hester’s work concerns itself with the search for identity. This is unsurprising given the expectation of women at the time was in the roles of homemaker and mother.

Untitled (from the Love Series), Joy Hester, 1949. Heide Museum of Modern Art

The interconnectedness of being with another is presented in this series in the shared eyes or mouths or the blurred boundaries between heads. By the time Hester came to The Lovers series (1955-56) the blurred boundaries between couples has been replaced with a sense of separateness. The heightened emotions of the female figure are foregrounded and they seem to encompass both despair and euphoria.

Words and pictures

A sense of intimacy is never far away from Hester’s unidealised images of children and maternity which appear throughout her work.

Some of her most stunning and poignant images are to be found in these works precisely because of the unvarnished way she presents the complexity of these fundamental relationships.

Girl, Joy Hester, 1957. National Gallery of Australia.

The same is true of her many poems, often exhibited in tandem with one of her drawings. Rather than presenting worlds full of conflict and heightened emotional states, her poems are delightfully sensual and capture the immediate joy of love and the beauty of nature.

The Heide retrospective of Hester’s work marks the centenary of her birth. It comes at a time when audiences have a much greater sensitivity to her important place in the canon of Australian modernism and as a deeply nuanced artist of the human condition.

The show groups the work together in ways that underline and highlight their emotional impact and provide an important opportunity to connect with the artist and her stunning imagination.

Joy Hester: Remember Me can be seen at Heide until 4 October though Heide is temporarily re-closing for six weeks from Thursday 9 July until 20 August 2020.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.