In recent weeks, the world has witnessed the power of protest.

Whether it be peaceful rallies in solidarity, violence and looting hijacking a cause, the changing of street names, to the symbolic painting of a Washington boulevard in view of the White House – the actions of the past three weeks have called centuries (yes centuries!) of racial injustice to account.

But rather than the usual fire and fizzle cycle, this movement continues to spread in a truly remarkable way. This week, America’s Merriam-Webster dictionary announced it will change its definition of the word racism to better reflect the oppression of people of colour; the police documentary series Cops has been dropped by the Paramount Network after 33 seasons; HBO Max has dropped Gone with the Wind, while Adidas and Reebok have vowed that 30 per cent of all new US jobs will filled with black and Latino people.

We are talking about a systemic change via big brands and popular culture. Now the colonialist statues and monuments that scatter our parks and public buildings have come under scrutiny this week – many never to return.

Toppling of King Leopold II, Antwerp Belgium. Instagram @nina_sanadze

HOW THE HEADS ROLLED THIS WEEK

Belgium hit the headlines with a petition in Belgium (1 June) to remove all statues honouring King Leopold II. He is the colonial dood said to account for the death of 10 million Congolese. Two days later (3 June), his statue at Place du Trône in Brussels was defaced.

‘Leopold II’s hands were painted red in reference to the blood on the King’s hands for the inhuman acts perpetrated in the Congo. Various inscriptions such as “assassin,” “f**k u” or “no justice, no peace” were also painted on the monument,’ reported the Brussels Times. It was then set on fire.

Further statues of the former Belgian ruler were defaced across the country.

Then attention turned to America, with the statue of Confederate General Williams Carter Wickham toppled from its pedestal in Richmond, Virginia (6 June). It was the start of a progressive “head roll” as further confederate statues were defaced and removed across the US, including a beheaded Christopher Columbus statue in Boston.

Across the Atlantic, it was the toppling of slave trader Edward Colston by Bristol demonstrators (7 June), and social media images of a protester appearing to kneel on the statue’s neck, before rolling it into the harbour, that made worldwide headlines earlier this week.

Launching the same day that Colston was toppled, Australian artist Tony Albert launched a new commissioned work by IMA (Institute of Modern Art, Brisbane), which takes a spin on Miley Cyrus’ famed Wrecking Ball song – pummeling Cook statues with a ceremonially painted Albert swinging on a chain (pictured top).

‘Through humour Albert implores us to rethink national narratives,’ says IMA Director Liz Nowell.

By this week’s end, nearly 30 statues of oppressors had been targeted globally.

Hyperallergic writes: ‘In two days, the British public have received more education about slavery than the entirety of their secondary school curriculum.’

The toppling of Colston in Bristol fell nearly five years to the day (April 2015) after a student at the University of Cape Town threw a bucket of shit at his bronze face of a statue of imperialist Cecil Rhodes – the architect of racial segregation in southern Africa.

It was the birth of the #RhodesMustFall movement, which stretched from South Africa to Oxford, in a demand for “decoloniality”, and is really the extension of what we are witnessing today.

Australia joined that conversation in 2017, when Captain Cook’s statue which stands in Hyde Park Sydney was painted with the words “change the date” and “no pride in genocide”. It has again been reignited this week.

What we are witnessing globally is a conversation that has moved well beyond apartheid or George Floyd to calls for a rethinking of the celebratory narratives bestowed on colonialist statues. It was as though the protests for the Black Lives Matter campaign had “picked the scab off” a festering wound – one that has been lingering for many years.

AUSTRALIA JOINS GLOBAL CALL TO REMOVE STATUES

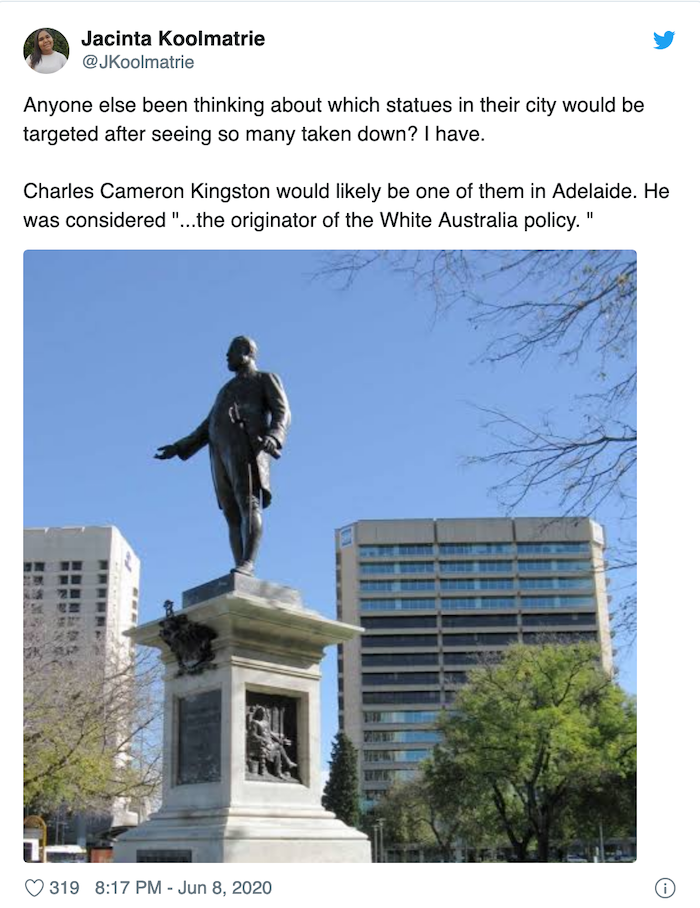

Archaeologist and Adnyamathanha and Ngarrindjeri woman, Jacinta Koolmatrie posted a photo of the statue of former SA premier Charles Cameron Kingston on social media this week. His statue sits prominent in a Adelaide’s Victoria Square.

Koolmatrie wrote: ‘Anyone else been thinking about which statues in their city would be targeted after seeing so many taken down? I have. Charles Cameron Kingston would likely be one of them in Adelaide. He was considered ‘the originator of the White Australia policy.’

South Australian actress Natasha Wanganeen told the ABC: ‘Looking at that statue every day as an Aboriginal woman, walking out of my house, it is a mental health trigger.’

‘I would support that statue being removed and being replaced with somebody who was respected by both white and black people here,’ she continued.

While celebrations around Cook’s 250th anniversary landing were overshadowed in April by the coronavirus pandemic, a month later the events in America have triggered a renewed round of calls for justice.

A statue of Cook in Melbourne was also targeted for removal – it had been bombed with pink paint in 2018 with the words “no pride” painted beneath his feet. Then treasurer Scott Morrison turned to twitter, criticising the vandalism.

Also mooted this week for removal was a 10-meter high concrete statue of Captain Cook in the centre of Cairns. It was first targeted in 2017, when a banner with the word ‘sorry’ was hung from it.

Statues of NSW Governor Lachlan Macquarie have also been cited for removal for his role in genocide of our First Nations Peoples, while Greens Senator Jordon Steele-John turned to social media to target WA’s first governor James Stirling, who led an attack on Aboriginal people in 1834 known as the Pinjarra Massacre.

Steele-John cheered protesters: ‘It’s great to see these symbols of white supremacy being torn down,’ reported AAP.

His comments came under the criticism of WA Liberal MP Tjorn Sibma, who said the senator was ‘deliberately importing stupidity and violence into the community’, labelling his remarks ‘an incitement to criminal behaviour, anarchy and vandalism.’

‘Freedom of speech, particularly that provided by public figures, demands an equal measure of public responsibility,’ Sibma told parliament.

It is the kind of polarising conversation that has long thwarted this topic.

DOES REMOVING STATUES REMOVE THE CONVERSATION?

How can the world forget the image of a toppled Sadam Hussein – a symbolic end of the Battle of Baghdad on 9 April 2003. Staged, or not, the moment could not foresee the spiralling conflict for years to come. What then did it achieve?

And indeed, what will be the fate of the 30+ sculptures toppled, defaced or removed this week?

Eusebius McKaiser writes for The Guardian: ‘These statues show a wilful disregard for the dignity of the victims of colonial heritage. The debate should be about what to do with the toppled statues and not whether to topple them. They belong in a museum with an accurate historical account of the sins of these men.’

While there has been a mob-like celebration in the defacing of these monuments, the opinions are deeply divided.

On one side – their removal is considered part of a healing process. The presence of these monuments are a persistent reminder of oppression and disrespect.

‘It’s great to see – very inspiring,’ CEO of Sydney’s Metropolitan Local Aboriginal Land Council Nathan Moran told SBS News. ‘We in the local community support the removal of statues that honour racist bigots and those who have perpetrated atrocities against our people.’

The alternate view is that by removing these statues and monuments we are no longer reminded of that past, as though it has been erased from public conversation.

This week, Mayor of London, Sadiq Khan, ordered a public inquiry into the potential axing of other memorials and street names with links to slavery on Tuesday, while North Carolina (USA) passed a resolution this week to begin a removal process for its confederate monuments.

There is, however, a movement to let them stand and re-sign these monuments to tell the true and full picture of these colonialists.

Images circulating on social media of protesters in Richmond, Virginia (USA), with memorial statue of Confederate General Robert E. Lee.

History can be defaced but history cannot be erased. We can rewrite history; we can make amends for history, but the past is unchangeable. Should these sculptures then not be used in a more proactive way to speak of history’s truth? A stripped pedestal covered in graffiti feels like a thin alternative to debate.

Australian National University history professor Bruce Scates is a proponent of what is termed, “dialogical memorialisation” – the addition of plaques to existing monuments to explain history from a modern perspective.

He told the ABC that removing statues altogether ‘removed that opportunity for discussion.’ His view is supported by Minister for Indigenous Australians Ken Wyatt, who told SBS News that,

‘These statues should remain as a reminder of a point in time in our lives – even when detrimental. They serve as prompts to encourage people to talk about history.’

‘As Indigenous Australians we have sought to have the true history of this nation told so that it reflects both Indigenous and non-Indigenous perspectives and history.’ He added: ‘In order for us to heal the past we need to have genuine conversations and understand the history of our nation.’

This will be yet another pivotal moment for Australia in how we address our past, and ensure our future narratives are transparent.