In March 1992, I stood in a queue with my fellow Year 12 students to see Funerals and Circuses by Arrernte playwright Roger Bennett at Theatre 62. We were on an excursion from Port Augusta. I had just turned sixteen. I had no idea what the play was going to be about.

A security guard approached two Aboriginal men standing in front of me and said to them, ‘Fellas, the pub is down the road.’

One of the men answered, ‘We’re here to see the show.’

I looked knowingly at the only other Aboriginal student in my class. We were well accustomed to seeing racism, prejudice and discrimination play out in its many forms in our hometown. In 1990, the Port Augusta council attempted to introduce a curfew, not even trying to hide the fact it was targeted at Aboriginal youth.

Again the security guard told the men to move on. The men pointed out that they were dressed appropriately, in good shoes, shirts and jackets, but the security guard increased his attempts to move them on.

One of the men took a ticket from his pocket and presented it, raising his voice and telling the security guard to get nicked. I was waiting for an adult to come to the aid of the men. It didn’t happen.

When finally seated in the theatre, I felt angry, embarrassed and downhearted reflecting on what I had just seen. During my teenage years I started to learn more about the racism that family members had endured, and that my people had been subjected to on a regular basis. It all seemed so insurmountable.

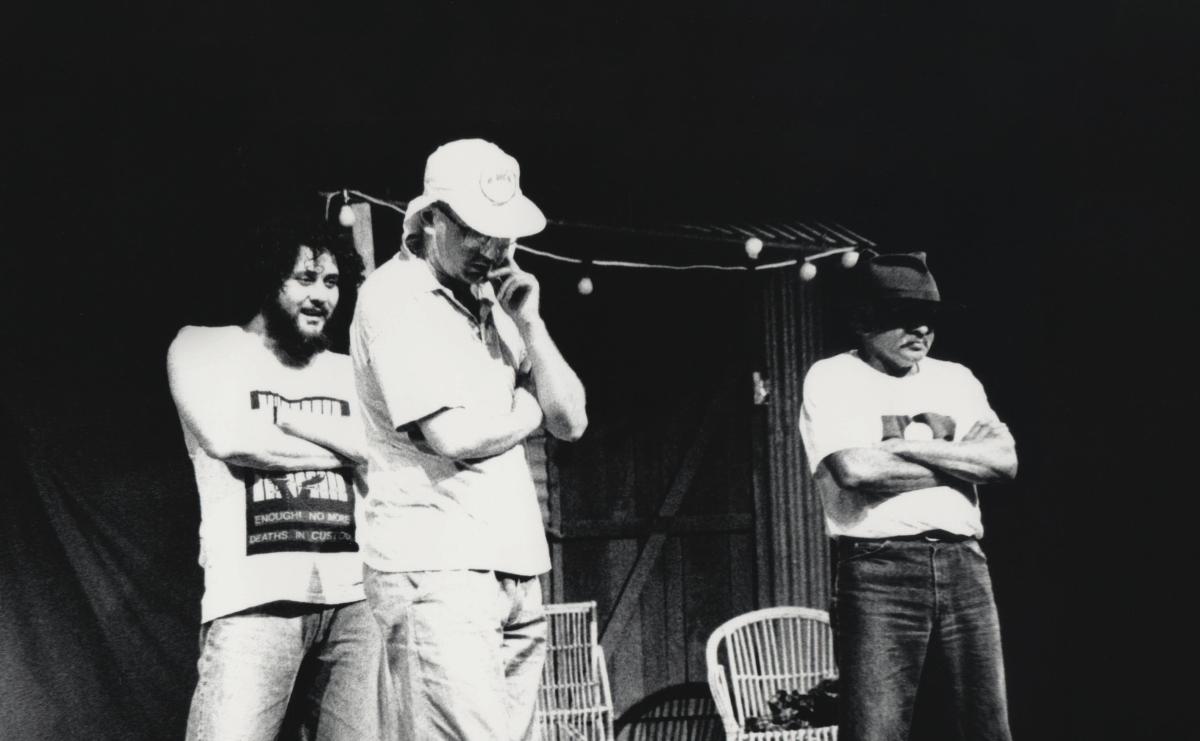

After a song by singer–songwriter Paul Kelly, the two Aboriginal men who were harassed earlier walked onstage. To everyone’s surprise, Robert Crompton and Michael Harris were actors in the show. They welcomed us to their town and challenged audience members, asking why they hadn’t intervened when bearing witness to explicit racism.

I felt that the men were speaking directly to me. It was so incredibly powerful and as I watched the faces of the audience I realised then and there that I knew about things that were worth telling; that I wanted to be a writer. This feeling increased the more I was immersed in the promenade-style theatre, seeing Aboriginal and non- Aboriginal actors work together to address the issue of racism as depicted in regional South Australia.

Before seeing Funerals and Circuses, I wasn’t overly academic. However, thinking about the play bolstered my efforts at school that year, and the following year I enrolled in a BA at Adelaide University with the aspiration of becoming a writer.

In 1996, towards the end of my undergraduate degree, I met Roger Bennett and Robert Crompton at the National Indigenous Writers and Playwrights Conference and Workshop. I was there to workshop my play Flash Red Ford, a story about my great grandfather’s experiences living in Port Augusta in the 1920s, which was representative of the type of racism I continued to see in my hometown and around the country.

Read: Adelaide Festival celebrates 60th anniversary by going carbon neutral

It was incredible to talk about Funerals and Circuses with Roger and Robert, and for them to provide feedback on my play. They were like superheroes. I had envisaged Flash Red Ford being presented in Port Augusta. In March 1999, it toured Kenya and Uganda.

Shortly after the production of Flash Red Ford, my life seemed to interconnect with other people who had worked on Funerals and Circuses. Director Rachel Perkins called me to work on the film One Night the Moon, a musical drama featuring Kaarin Fairfax and Paul Kelly. For Funerals and Circuses, Kaarin had worked as assistant director and Paul acted in it and composed the music.

In 2002, my play Love, Land and Money was produced by Geoff Crowhurst of Junction Theatre Company. Funerals and Circuses’ designer Kathryn Sproul was designer of Love, Land and Money, and actors Robert Crompton and Michael Harris joined the cast.

I often wonder what my life would have become if I hadn’t attended the 1992 Adelaide Festival and seen Funerals and Circuses. Before that time, no one would have envisaged that I’d become a writer.

During Festival time I often think about the young people who will engage with the shows, perhaps experience a particular art form for the first time, and be moved and activated by it in a way that will also change their lives.

This essay is from Adelaide Festival: 60 Year 1960-2020 marking the anniversary of South Australia’s best-loved arts festival and is available from Wakefield Press.