Survey exhibitions offer an artist a moment of reflection: How does an artwork hold up?, especially when making politically toned, the question whether the topic has improved or impounded is a pertinent one.

Campbelltown Arts Centre’s exhibition Vernon Ah Kee: The Island is a great example of the power that a reflexive moment can offer, both for the artist and audience.

In a nutshell, to answer that former question, little has changed.

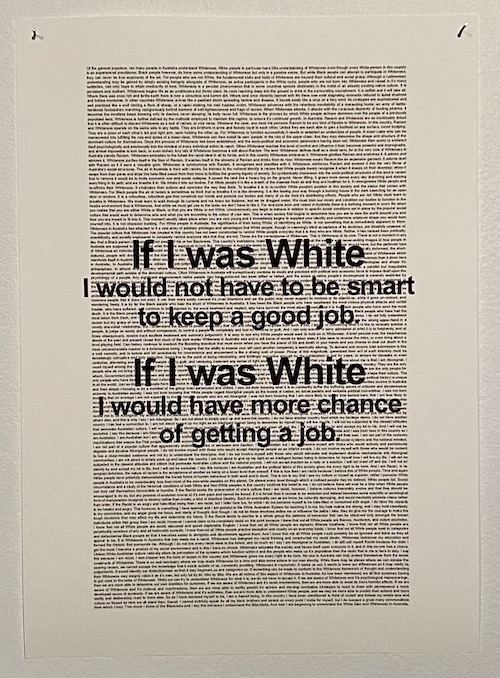

From the earliest work by Ah Kee in the exhibition, if I was white (1999-/2002) – a wallpaper of A4-sized texts that touch on the anguish of living under systemic discrimination – to a suite of three hand-painted doors from the demountable school block of the Yuendumu school, presented here just weeks after Warlpiri man, Kumanjayi Walker was shot at the hands of police – this exhibition is testament that we are still facing the same problems of racial violence two decades later.

Vernon Ah Kee, if I was white (1999-/2002), inkjet prints, series of 30 prints. Courtesy artist and Milani Gallery. Photo ArtsHub.

The Yuendumu Doors are presented in tandem with a suite of doors removed from a toilet block on Cockatoo Island where migrants were held and worked, represented by Ah Kee as the work Born in this skin (2008) in the 16th Biennale of Sydney.

Ah Kee bares witness to the ingrained, and endemic, play of racial commentary within Australian culture, extended to generations of migrants and refugees alongside Aboriginal people – onshore and off.

One starts to understand, viewing this exhibition, the complexity with which narratives are woven and entrenched.

Installation view Campbelltown Art Centre, Born in this skin (2008) and Yuendumu Doors. Image supplied

Moving around this exhibition there is a greater weighing on Ah Kee’s video practice, more than we have seen in the past. The 2017 survey of his work presented by NAS Gallery, Not an animal or a plant, had no video work included.

Queensland born, Vernon Ah Kee has established a reputation for his probing, provocative and yet deeply sensitive artworks over the past two decades. Working closely with C-A-C Curator Adam Porter on the presentation of this exhibition, many of the works and video screens have been suspended – a kind of metaphorical lynching – the floors and walls blackened in the space.

Furthermore, a number of walls have been angled so as to push the viewer into a tighter bodily engagement with these works. Porter told ArtsHub: ‘You’re meant to feel a bit uncomfortable. It is a consistent feature throughout to reshape the space, and push viewers up against the screens to engage with it in a much more meaningful way, rather than a cinematic way.’

And it works. A good example is the video installation Kick the Dust, created last year. Ah Kee has expanded the 3-channel video for C-A-C to include fragments of the riot shields from the video, smashed over a rock (pictured top). While the installation takes its cue from an event in the USA where a black man was dragged behind a ute, its parallels to racially motivated violence in Australia are not lost in this exhibition.

A consistent topic in Ah Kee’s work is what police (and also enforcement officers with asylum) mean in terms of frameworks of power that keep minority voices suppressed.

That tone has been set from the outset of this show – you can’t not feel its palpable load. What is usually a thorough fare into the galleries – a warm, light entry – is populated by riot shields that are suspended in the space so as to force a bodily engagement. These police shields are also inverted, a device used across this exhibition as a soft (well not so soft) metaphor to lynching.

Titled Scratch the surface, Ah Kee has literally scratched back into these shields with charcoal, adding that human element and a kind of rupture of the trauma they signify.

Installation view Campbelltown Art Centre, Scratch the surface (2019) and whitefellanormal/blackfellame (2004). Photo ArtsHub.

They are shown with Ah Kee’s first video work, whitefellanormal/blackfellame (2004), a tiny screen in a sea of black wall, its content amplified into steroid proportions as a text wall work black-on-black.

In separate rooms Ah Kee and Porter revisit earlier seminal works – the four channel video that looked at police brutality on Palm Island (QLD) in tall man (2010); and in another his signature use of surfboards (also suspended) which allude to the embedded racism, and exclusion, in surf culture.

In their rethinking of the older work, tall man, Ah Kee has expanded the video with a text wall piece, fill me, and two charcoal portrait paintings of Lex Wotton. They are the only drawings in the show.

Vernon Ah Kee, tall man (2010, video installation. Image supplied.

Central to this survey, however, are two important multi-channel video works. The exhibition takes as its launching point as Ah Kee’s The Island (2018), commissioned by Griffith Uni Art Museum to coincide with the Asia Pacific Triennial. It is was perhaps the first work that Ah Kee punched the video’s dialogue out in a more considered way as large vinyl text works.

It is a technique that Ah Kee has expanded in his practice in recent years, with all the video works in this exhibition (both revisited works and new works) employing this technique.

The Island offers a strong anchor to Ah Kee oeuvre, and segue to a new piece commissioned by C-A-C for this survey, lullaby (2019) – a six channel video of Farsi-speaking refugees, a mother and her young child.

There are no English translations anywhere. It was a deliberate choice by Ah Kee, who wanted to amplify a way to pass on culture, and the universal language of action, movement and gesture, as a cultural expression.

Across this exhibition, we start to – collectively – grasp the power of communication, albeit elders storytelling through school doors, racial graffiti on a toilet block, or the communication of a child and mother benign of words. The message is one of resilience and respect – no longer one of repression as the status quo.

Ah Kee gives us a hard hitting exhibition. It is an incredible body of work – superbly considered in the gallery space – and leave us carrying something away with us that is lasting.

Ah Kee is a descendant of the Kuku Yalandji, Waanji, Yidindji, Koko Berrin and Gugu Yimithirr peoples.

Vernon Ah Kee: The Island is co-presented with Sydney Festival, and it will be toured by Museums & Galleries NSW for a two-year period, starting in early 2022.

★★★★★ 5 out of 5 stars

2 January – 23 February, 2020

Campbelltown Arts Centre (NSW)