With eight engineers, eight artists, and around eight months working together, the Manly Dam Project opened at Manly Art Gallery & Museum (MAG&M) in December.

Arts and science collaborations are not new; indeed, we have become quite sophisticated in how artists and scientists have shared conversations today. It’s less about taking from each other, and rather about a way to speak in tandem for a shared outcome.

Co-curator Ian Turner – a scientist and director of UNSW Water Research Laboratory (WRL) – writes in the exhibition catalogue, ‘Creativity is at the core of both the arts and scientific research.’

The collaborative project marks the 60th anniversary of WRL, an internationally recognised facility on the edges of Manly Warringah War Memorial Park, and once the drinking water source for Sydney’s north.

The Manly Dam Project is particularly poignant at this time, when our nation is in drought and the conversation of building more dams is on the agenda.

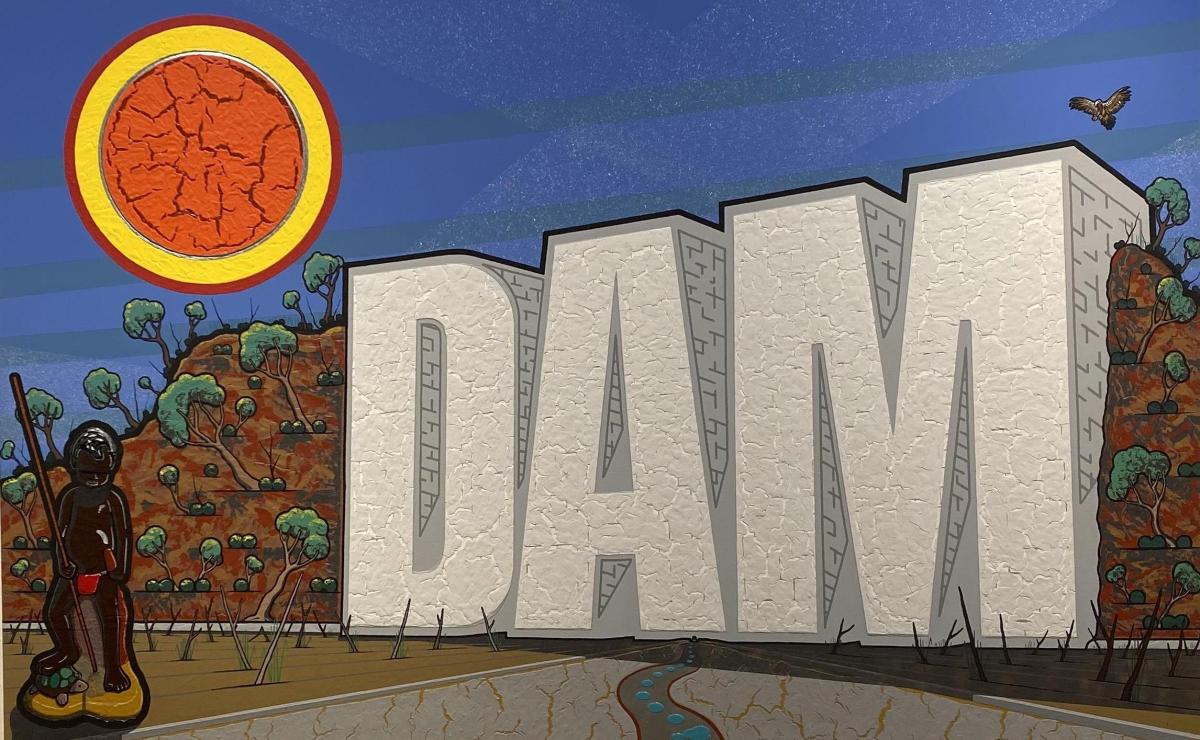

Not everyone thinks that’s a good idea. The title of Indigenous artist Blak Douglas’s work in the exhibition – Dam Nation (pictured top) – is a particularly direct response to this debate.

He writes: ‘The strangulation of a natural flowing water source represents a commensurate trophy of colonisation of another people’s land.’

In his work, a kitsch garden ornament of an Aboriginal figure is overshadowed by a walled edifice declaring ‘DAM’ – the message of fragility thrown out of balance is clear.

Spending time with this exhibition, it is apparent that the artworks fall into two distinct engagements – works made using the dam (literally), and works made responding to the dam and its complex narratives – its biodiversity, social history, Aboriginal culture and engineering.

Nicole Welch offers an interesting counterpoint to Douglas’s works: her infrared time-lapse video Yarrahapinnin (2019) records tidal flow into an estuary and wetlands. Constructed from 4,800 photographs captured over several hours, the notion of time mirrors scientific methodologies of research and environmental repair.

Nicole Welch, Yarrahapinni, 2019, Single channel video, gilded frame. Image courtesy of the artist and May Space.

Nicole Welch, Yarrahapinni, 2019, Single channel video, gilded frame. Image courtesy of the artist and May Space.

The Yarrahapinnin Wetland Restoration Project has successfully rejuvenated the water quality conditions from a once highly acidic wetland. Without a sound element, it appears like an Old Master painting in a gilt frame – there is a timeless to this work, that reminds viewers that impact is a very slow journey to reverse.

Similarly, Shoufay Derz uses the dam itself across her somewhat surreal suite of photographs, Loving the Alien (2019). She explores concepts of disconnection, embeddedness, loss and the unknown, weaving the environment, its past custodians and history into a narrative that is vibrant and slightly unsettling.

Shoufay Derz, Loving the Alien, 2019.

‘A hidden silence reached out across the great muteness to meet the silence in the other,’ writes Derz, adding that, ‘the water is the mysterious element…these are not my stories but it’s important for me to listen to them.’

It is not surprising that many of the works in this exhibition take a poetic tone to tackle complex stories.

Sue Pedley uses materials from the dam itself – water, sludge – in her large-scale drawings of the ancient fish, Climbing Galaxias, which inhabited these waterways. Her installation Otolith: in the ear of the fish (2019) fuses impressions with scientific imagery, engineering plans and texts.

Sue Pedley, Otolith: in the ear of the fish, 2019. Installation view at MAG&M. Photo: ArtsHub.

Similarly, Cathe Stack draws on various sources in her series of sculptural works titled Changing line of Coastline (2019).

The WRL is internationally recognised for its Wave Flume 3D modelling, ranked 12th in the world, ahead of Stanford University in the USA. Working in a mode of data visualisation, Stack has interpreted wave dynamics and sea levels rising with climate change and coastal erosion. Her sculptures hover in the space in a kind of delicate balance; their rhythms and patterns metaphorically pointing to the fine-tuned complexity of such systems of management.

Playing off that idea of the landscape’s palpable vibration, Nigel Helyer has taken the most direct use of science in his sound installation.

The gallery is filled with the sounds of a double base and bassoon, a recording by the London Philharmonic. Drums with sand and pods on their surface become percussion instruments – their amplified vibration and rumble through the gallery almost an urgent call to action to listen to nature, its patterns and its plight.

Nigel Heyler, Sonus Maris (the sound of the sea), 2019. Installation view at MAG&M. Photo: ArtsHub.

This exhibition sets the tone for 2020.

This is not only a narrative of water and how we have historically managed it, but is an example of how we can use science to learn better practice. Helyer’s sound installation uses data collected over the last 43 years about the shifting sand volumes at Narrabeen beach in Sydney’s north. As he said, ‘…from this long-term view it is possible to identify an accumulated effect.’

‘It is our point of view along the axis of the particular to the general that allows us to see the wood from the trees,’ he continued.

For 60 years, water from Manly Dam has been temporarily diverted to WRL’s three warehouse-sized laboratories where experiments are undertaken to better understand the critical role water plays in our catchments, from groundwater knowledge, biodiversity, hydraulics, renewable energy and climate change adaptation, before being released – unchanged – back to the Manly Creek water system.

We need to be better at listening to our scientists and artists.

4.5 stars out of 5 ★★★★☆

Manly Dam Project

Curators: Katharine Roberts and Ian Turner

Artists: Shoufay Derz, Blak Douglas, Nigel Helyer, David Middlebrook, Sue Pedley, Melissa Smith, Cathe Stack, Nicole Welch.

Engineers: Ian Coghlan, Chris Drummond, Francoise Flocard, Mitchell Harley, Alice Harrison, Tino Heimhuber, Gabriella Lumiatti, Ben Modra.

6 December 2019 – 23 February 2020

Manly Art Gallery & Museum (MAG&M), Manly NSW