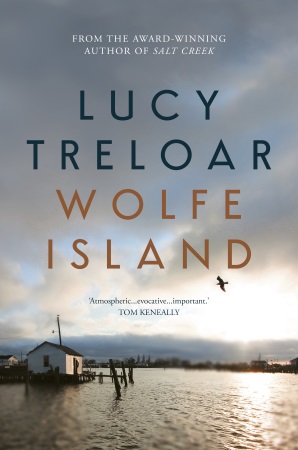

The spectres of climate change and social breakdown haunt the edges of Wolfe Island, the second work of fiction by Australian author Lucy Treloar. As the local population contends with rising seas, summer storms, stunted plants, vanished bees, and encroaching salt, authorities on the mainland turn a blind eye to the militias and vigilantes that roam neighbouring counties. Zealots fell wind turbines and destroy solar fields in preparation for the rapture. It’s a world of ‘runners’ where refugees are hunted and distrust reigns.

Against this dystopian backdrop, we meet the improbably named Kitty Hawke, the last remaining resident living on Wolfe Island, a fictional island off the northeast coast of the United States, in the Chesapeake Bay. Once a thriving community but now an almost-uninhabitable marshland slowly being reclaimed by the ocean, Wolfe Island’s population relocated to the mainland years ago, leaving the stubborn Kitty to preserve a dying way of life with no one for company except for her beloved wolfdog, Girl.

She’s free to trawl (she calls it ‘mudlarking’) the island’s shores for materials for her ‘makings’ – sculptures that have earned her a reputation and an agent on the mainland. Of some renown thanks mostly to a documentary made about her art, Kitty must endure the tourists who sometimes turn up uninvited to meet the reclusive artist. Over winter, however, she might go months without seeing another person.

Innumerable bonds of history and blood tie Kitty to Wolfe Island. ‘Thready roots connect me to the island everywhere I go,’ she tells us. Her everyday furniture is a collection of ‘antebellum’ antiques (her agent’s words), the kitchen table dating back to 1680 when her forebears settled the island (Hawke, we learn in the novel’s opening pages, is the ‘oldest name on the island’). Every inch of the island elicits a memory, or a story handed down the generations. ‘Nothing on Wolfe is truly strange to me. I have a memory for every part of it,’ she notes. Visitors see “’a ghost town, cold and ruined’, but Kitty recalls ‘lit windows, people moving through light, laughing and talking, children running, crowds in summer, parties and festivals…’

Into this solitary state of decline arrive four young newcomers: Kitty’s 17-year-old granddaughter Cat, her boyfriend Josh, their friend Luis and his sister Alejandra. In her gruff way, Kitty makes them welcome and respects her granddaughter’s wish to keep her location a secret from her mother, Kitty’s daughter. On the run – from what, we’re not told – the four set up house in one of the island’s many empty dwellings. Kitty bristles at the intrusion of strangers into her world: ‘It was exhausting being around people,’ she writes. ‘It used to be that I could forget myself and be, spend hours in the marshes … I missed that.’

Despite her reclusive nature, Kitty soon establishes fond relationships with Cat, Luis and particularly the young Alejandra, who kindles within her a strong maternal impulse. She comes to realise that she would do anything she could for them – a declaration that is soon put to the test.

Inevitably, danger arrives, usually in the form of men, and Part II of the book sees Kitty and her young companions embark on a journey north to find sanctuary across the border. In a world where you need your papers to be safe, it’s a perilous road trip marked by violence and fear – and resourcefulness. Kitty and her companions sleep in abandoned houses, their world reduced to the basic needs of food, warmth and shelter. Evidence of society’s devolution is everywhere. Their arrival in a city throws into sharp relief the extent of the decline – them homeless and unwashed, the metropolis full of abandoned and defaced buildings.

Wolfe Island is also the story of Kitty’s reckoning with motherhood and the way it relates to her sense of self and her art. ‘Sometimes we fail, as I did with my children,’ she acknowledges. We witness the metamorphosis of new motherhood – ‘whatever you’ve felt before means nothing’ – and encounter examples of ruptures, reunions, and fierce maternal love that recur throughout the book. ‘Mothers,’ writes Kitty, ‘will do a lot to protect their children.’

Treloar pays the same painterly attention to Wolfe Island’s coastal landscape that she does to the arid and exposed mouth of the Coorong, the setting of her 2016 debut, Salt Creek. ‘The marshes were as beautiful as I ever saw them,’ observes Kitty in summer (her last on the island), ‘speckled with pink mallows and banks of snowy marsh hibiscus, their buds unfurling and shrivelling within a day, and the orange trumpet flower vines and honeysuckle scrambled and hung from every building, scenting the heavy air until every bit of it was sweet.’

Part III, set several years after Kitty’s journey, offers some answers. There remains the uneasy sense that the drama of Wolfe Island occurs in the twilight years of society as we know it – ‘like looking out at the end of civilisation.’ In our current moment of anti-immigrant rhetoric and political inaction on climate change, Treloar’s dystopian tale is couched firmly in plausibility.

4 stars out of 5 ★★★★

Wolfe Island by Lucy Treloar

Imprint: Picador Australia

ISBN: 9781760553159

Format: Trade paperback

Categories: Fiction

Pages: 400

Release Date: 27 August 2019

RRP: $29.99