Sculpture department at National Art School, Sydney; image supplied

Sculpture has long been one of the core disciplines taught at art school, however within those departments a kind of push-and-pull between tradition and technology has arisen, as new methods impact sculptural practice in the 21st century.

At the Sydney Sculpture Symposium earlier this week, a panel of international educators and artists asked important questions about what is lost and what is gained as teaching styles change, and whether our degrees have become too short.

Dr Michael Hill, Head of Art History and Theory, National Art School, Sydney (NAS) made the important point: ‘How does sculpture, given its tradition, and that it’s heavy and expensive and really hard to establish a practice – which means you can’t be too promiscuous in how you treat your practice – attract the younger minds?’

Hill said he is chuffed to see that students are still working with modelling clay when he walks around the NAS campus, but added that ‘tradition is not enough of an answer,’ when shaping a curriculum.

Are digital approaches interrupting skills-based traditions in sculptural education?

In the light of digital modelling and 3D printing creeping into the curriculum of many art schools today, Hill prompted the question: are we headed in the right direction for our future artists? Are we loosing that vital sense of touch as we move away from hands-on study?

Hill believes that hand skills are not dead, noting that most applicants hoping to enter the sculpture department seem to “gesture” their way through their interview.

David Horton, artist and Head of Sculpture at NAS, agreed: ‘We take the view that clay is the best material to introduce new students to sculpture because of its plastic nature – it is a material where you can describe the subject really well – to transcribe what they are seeing.’

Horton said that traditional skills are important for developing dexterity. ‘One exercise I get first year students to do is to model an elephant behind their back. It is a known form, and the manipulation of that clay behind the back is extraordinary.

‘It is a very useful act for getting them to notice things,’ he added.

Hill said that in America, students are trained to do two-handed carving, while Professor Lv Pinchang, Dean of Sculpture, Central Academy of Fine Arts, Beijing said that in China they pay great attention to foundational skills and modelling ability in the first five years of their degree.

‘We always believe that as an artist the basic skills, and the practice of your ability, is very important,’ said Pinchang. ‘When the Western world actually moved away from the traditional realist training, China kept that tradition. Nowadays, we have a lot of young sculptors come from overseas to the school to train in this method. We still believe the foundational trainings in realism are the keystone in an artist’s ability.’

For a country with an education system so steeped in tradition, Pinchang demonstrated that being adaptable to change is also important.

‘Of course, we are now in a new age, we must adapt to the global trend … The emergence of electronic media and new technologies have [had a] huge impact on development of society in China and consequently impacts on our teaching. We believe introducing the new technologies can enhance a student’s imagination.’

Wendy Teakle, artist and former Head of Sculpture, Australian National University (ANU) Canberra said that the curriculum has changed radically in recent years.

‘It’s really important that people learn how to use their hands – to think through their hands. Even if you are not going to be an artist that’s very hands on – and rather, do a model and take it out to industry to fabricate – if you don’t know how it works you are not going to be able to talk with the people who will make it,’ Teakle said.

Teakle said that those traditional lessons in modelling clay and making moulds are dropping out of the curriculum in Canberra, and are being replaced with 3D printing.

‘That is great in terms of a connection with new technology but for a student to print a work it might take 10 hours. If you put ten students in a classroom with a teacher who knows how to make a model, it might take just a couple of hours to [pass on those skills].

‘Technology is not the “be all and end all”; it should be integrated into the curriculum but not take over from some of the traditions,’ Teakle added.

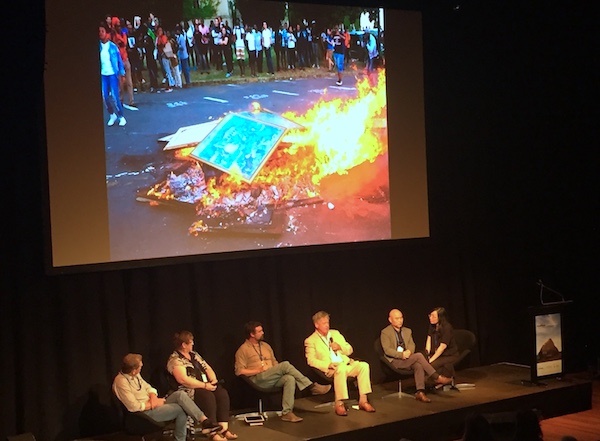

Panel of international art educators at Sydney Sculpture Symposium 2018; L-R Michael Hill, Wendy Teakle, David Horton, Gavin Younge and Professor Lv Pinchang; screen image art student protests in South Africa; photo ArtsHub.

A diminishing curriculum

3D printers are not new. Hill believes that within five years they will be “everywhere”.

‘Kids ten years from now who are applying to art school will have grown up with that technology, so we need to start thinking now how sculpture departments will face that,’ said Hill, with regard to how curriculums need to be responsive to our times.

Teakle, however, believes that the root problem goes back further – to the education our kids receive in primary and secondary schools.

‘Very few schools teach sculpture because of WHS [Work Heatlh & Safety] – you have to do a risk assessment on a pair of scissors, let alone a chisel or a power tool. It is an issue that, as a society, we are becoming such a “nanny state” that we are stifling our capacity to experiment,’ she said.

Teakle added on a positive note that from her experience, despite the ratcheting up of tech-education and quashed creativity, that when kids get to art school all they want to do is ‘get dirty’.

Hill added: ‘So it might be the young that drive us from that conservative path in the future?’

Horton agreed. ‘Carving is the most counter-culture thing you can do because it is slow. In the instant gratification age we are in, we are finding the novelty factor of doing something and watching it evolve in slow time is more appealing [for students].’

Teakle noted: ‘Being tied up within the University system in Australia has been a bit of a tragedy for most art schools. There is less and less time to stand on the floor and talk to the next generation of artists.’

She said that the greatest problem we face, on top of diminished hours and skills transference, is the loss of wisdoms passed on by practicing artists.

‘Art school is about an [emerging] artist being taught by an artist who really knows their skill – their craft – and who can balance that with conceptual thinking, building that in others from the ground up,’ said Teakle.

‘I think the difference between China and Australian [art schools], for one thing, is that our degrees are getting very short and that concerns me. Something that we have to do in Australia is to wrest the education system back from economic rationalists and actually think about philosophy and culture – it is absolutely critical.’

She continued: ‘As we add new technologies, we also need to add time for students to learn those skills – both with the hand but also with the mind. It is very important they learn to think as well as make.’

Professor Gavin Younge, artist and former Head of Sculpture, Michaelis School of Fine Art, Cape Town (South Africa) explained that, like China, their degrees also of longer duration than those in Australia.

‘However, if one studies architecture for five to six years, one is qualified and can walk into a practice and the industry recognises you immediately. But in case of fine art or sculpture you qualify and there is no job to walk into,’ Younge said.

The implication was that while there is a need for a longer degree, there is also a need for society to better integrate artists professionally into work streams.

The humanity of sculpture

Teakle believes we are getting better at embracing sculpture, noting that at this year annual Sculpture by the Sea festival in Bondi, she saw people showing more respect for the work. ‘I didn’t see kids crawling all over it – they don’t crawl over BMW cars so why crawl over sculpture – it is about teaching appreciation.

‘I could [also] see people looking and asking questions. And there is a memory around things – conversations about pieces from previous years. That embodiment is interesting; Sculpture by the Sea has actually claimed that space,’ said Teakle.

She believes that talking is a key part of sculptural practice. ‘The other thing that tends to happen in sculpture departments is that people are talking to each other. You need that camaraderie. There is often no way to make a piece without help from others, and that constantly happens with sculpture. That sense of generosity is also something you learn when you are in that collaborative teaching environment.’

Horton said the best piece of advice he received as a student at art school was from a teacher and practicing artist.

‘I was working within the tradition of assemblage and my teacher said, “Look, this has been done before but it hasn’t been done by you”. That was incredible wisdom. I was enjoying myself and feeling an affinity with the material, and that [comment] gave me license to go on.

‘That is an important aspect of teaching – not just the training, but the mentorship embedded in that artist-student relationship,’ said Horton.

Both Horton and Teakle pointed to the future peril of that being removed – or too watered down – from the teaching environment.

This article is based on the panel discussion, Tradition and Trajection in Education, presented on 5 November 2018 at Sydney Opera House as part of the Sydney Sculpture Conference 2018, presented by Sculpture by the Sea.