Theatre queue for Regent Theatre (taken for Fox Films) 1946. State Library of NSW hood_21601.

This exhibition took me back to my twelve year-old self, when they decommissioned Dazzleland in the Adelaide CBD. The loss of my beloved indoor rollercoaster is a personal nostalgic pain but it is familiar to anyone who has seen the demise of a loved building. Demolished Sydney explores this scene 13 times over with much more famous and important sites, in the hope that on leaving the exhibition, we will look up and enjoy what we see and, if necessary, say goodbye.

What’s lost in the demolition of an iconic building is more than a pleasant layout or an old-timey façade. The surprise demolition of the heritage-listed Corkman pub in Melbourne recently prompted a deluge of tears and ink, with many locals sharing tales of dim nights in the front bar. There were calls for the developers to rebuild the Corkman site just as it was, an urbane revolt turned out to protest gentrification at the price of history.

The idea that a historic building can be rebuilt is, of course, ironic. ‘The patina, the texture of age is the important thing, and can never be restored. Value is built over time, not intentionally constructed,’ said Director of Curatorial and Public Engagement at Sydney Living Museums, Dr Caroline Butler-Bowdon.

Rowe Street, photographer unknown, 1929. City of Sydney Archives: 037/037868.

The eras layered in the Sydney skyline are a perfect example, said Butler-Bowdon. That ridging sweep over the water is the product of countless building sites, demolitions, and more building to squeeze a little more use out of the same old land. The Sydney Living Museums exhibition painstakingly documents and evokes the boroughs and sites that used to dominate the cultural compass of the city’s inhabitants. Salvaged fragments of buildings are all that remain of some of Sydney’s most beloved locations, on display beside photographs, film and artworks depicting the great edifices of another time.

Progress has little patience with history. We don’t build on ruins in Australia: we sweep them away. We can watch history disappear under the brick dust, and forget it was ever there. It might seem a shame, but Butler-Bowdon said the exhibition is not about bemoaning change. ‘We built what we needed at the time in the way the technology of the era allowed, and our needs change.’

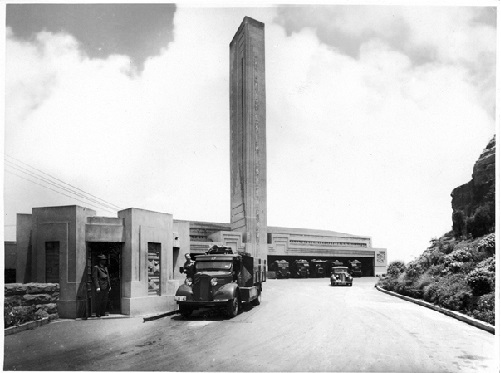

Take the old incinerator in Pyrmont – the city didn’t need an Art Deco refuse fire in the middle of the city any longer. Beside its stately beauty in photographs it no longer held value as a building, and so it made way for progress.

Pyrmont refuse incinerator, photographer unknown, late 1930s. City of Sydney Archives: NSCA CRS 538/254.

The city makes sacrifices to the needs of the inhabitants. If a city like Sydney wants to build among its winding byways and steep harbour walks, it has to take something down. It squeezes new buildings among the old, creating layers of stratified history.

By 1972, the city no longer valued the elegant mini-bohemian enclave of artist shops and boutiques known as Rowe Street. It replaced the underground bookshops lined with copies of Lady Chatterley’s Lover and the original Theatre Royal with the MLC Centre instead, including a bigger version of the old theatre and a different style of elegant shops. The Hotel Australia was the grandest hotel in the city for 80 years but, when the last customer checked out in 1971, sentimental value couldn’t save its antique wiring and old carpets. When industry started to diversify in the CBD, the Carlton United Brewery sat huge and wide on Broadway, taking up its space luxuriantly and, to the modern need, almost wastefully. Time was up on the old orange and brown building that had made such an impression on millions of people over its lifetime.

Carlton United Brewery, Broadway. Photo: © Alex Mattea.

The Rural Bank was demolished in 1985, a few years before the cultural resurgence of Art Deco which might have saved it. Seen through the eyes of a 1980s Sydney, the bank’s soaring edifice and imposingly monolithic forms look extravagant and imposing. But some people saw glamour in the building, and mobilised, too late, to save it. The campaign was unsuccessful, but from this disappointment Art Deco lovers went on to save other buildings via a shared admiration for grand Sydney architecture.

It seems cruel that an important place can stop mattering, but nostalgia can’t beat the vicissitudes of the real estate market or meet the needs of a bustling and cramped metropolis. The message of this exhibition isn’t slavishly protectionism, but a call to appreciation, said Butler-Bowdon.

‘Demolishing Sydney isn’t trying to inspire nostalgia. There’s a fascinating story of a changing city behind every demolition. We need to look up and around. We need to discover more about the history around us now, because your city won’t be this way forever. A good city takes parts of the old and the new, it needs juxtaposition and variety for people to love it.’

Demolished Sydney runs from 19 November 2016 until 17 April 2017 at Museum of Sydney, entry included in admission ($12).

Hotel Australia. State Library of NSW – PXD 1083