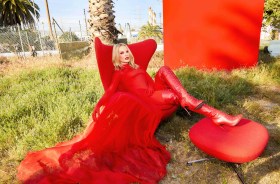

Sarah Goffman, Scholars Desk 2016/17, PET plastics, enamel paint, permanent marker; Installation view I am a 3D Printer at Wollongong Art Gallery; courtesy the artist.

Plastic is a material ubiquitous to contemporary life, but not always one we associate with fine art. Ironically, ceramics and sculpture were at one point described as ‘les plastique artes’, a term largely forgotten today.