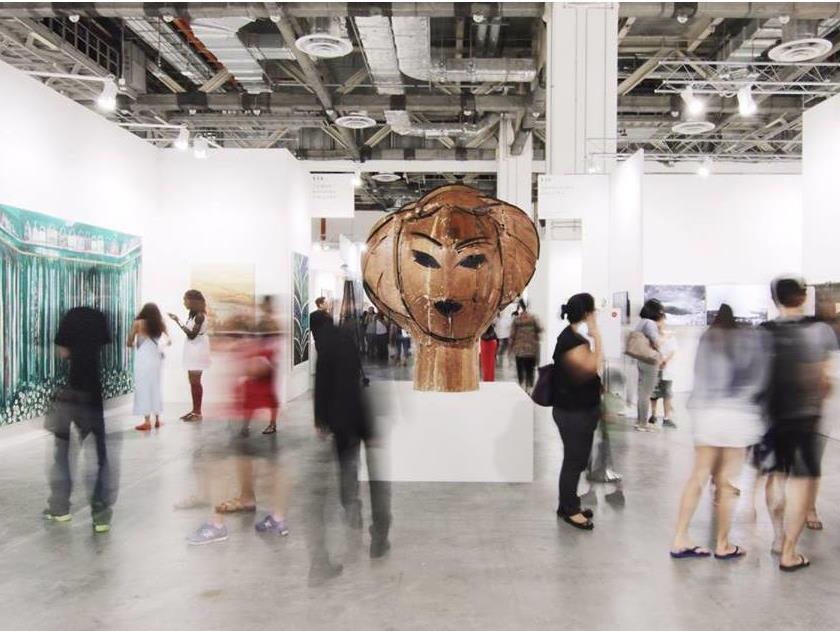

Art Stage Singapore 2016; source facebook

Any regular visitor to Singapore is persistently surprised at its rate of change. From trip-to-trip new train lines have been built, favourite restaurants have been razed, the architecture is increasingly adventurous, and more museums join the list.

While many bemoan the nation’s flaws, the familiar catch cry remains – ‘Singapore works’.

Over the past two decades, the Government has made a conscious and strategic decision to turn the city-nation into a cultural hub, second to its brand as an international economic hub.

It has spectacularly built state-of-the-art museums, collected vigorously, imported arts professionals, developed arts precincts, and created an art market. It is a complex ecosystem where all the boxes have been ticked.

But does it work, and what place does Australia play in this regional scope?

Culture is good for business

The global trend of recent years has recognised that creative cities feed creative business. Terms like “distrupters” and “innovators” have entered business language, ideas that champion creative thinking as a means to attain economic success.

Singapore historically has been a trade and financial hub. Since it became an independent nation in 1963, it has reinvented itself from a kampong (village) to an international city.

Culture has always existed but largely was in the background. However, in the past two decades it has become a priority agenda that continues to escalate.

We have been witness to the emergence of the Singapore Biennale, Art Stage Singapore (as well as other art fairs), seen investment in public art, the new ICA art school and gallery at La Salle, development of the art precinct Gillman Barracks and, most recently, the new $532 million National Gallery of Singapore, which opened in November.

Read: New Singapore National Gallery repositions SE Asian art

Clearly, Singapore believes good culture is good business and is using cultural investment as leverage in its economic positioning.

Buying it in

The National Gallery Singapore (NGS) has a charter to collect the region. The inaugural exhibition Between Declarations and Dreams references the country’s self-conscious construction through aspiration and nationalist verve.

The exhibition shows the history of Southeast Asian art and its inextricably connection to the region’s tumultuous social and political past.

Australia is not included in that dialogue, and the small handful of artworks in the gallery’s collection are there by default as gifts.

Three Australians however are part of the curatorial team at NGS, imported for their expertise. Singapore has become a master of identifying what it “needs” to construct this global cultural brand, and buying it

A good example of this canny importing is the art precinct in former military buildings, Gillman Barracks, which was established in 2012 with a roll call of international galleries seduced by good lease deals and lead by the vision of Eugene Tan.

It had optimism in a flourishing new market with the aim of building a more permanent presence upon the seasonal successes of Art Stage Singapore and Singapore Biennale.

Tan left about a year into the job to head up the NGS and management changed, vision was lost and now, just four years later, there has been a change of the guard of galleries. Opening of the cornerstone – NTU Centre for Contemporary Art Singapore (CCS) – was delayed more than a year, putting a dint in the aspirations of the Gillman project. It is only now gaining traction.

Some have called it a failure – a huge white elephant – while others, an experiment still running its course.

The Australian presence

In that first generation of Gillman, Australian artist Jasper Knight, Sydney-based Nina Miall, and Southeast Asian-based curator and writer David Teh set up the gallery Future Perfect. It has since closed.

Coinciding with Art Stage Singapore this year, Sydney gallery Sullivan + Strumpf announced it will open its first off-shore space at Gillman mid this year. While its directors recognised that it was a leap and a gamble, they also believed that it was important for Australian galleries to think, work and sell regionally.

Read: Archibald winner Sam Leach takes on Singapore’s Gillman Barracks

Australia had a further presence at Gillman during Art Week with the exhibition Antipodean Inquiry curated by former editor of Artist Profile magazine Owen Craven for Yavuz Gallery. The art was strong and somewhat tough for a Singaporean audience, erring on photography, which is a harder purchase in that collecting climate.

Owen’s project was one of a number of Australian-Singapore partnerships that took centre stage during last week’s fair and festival.

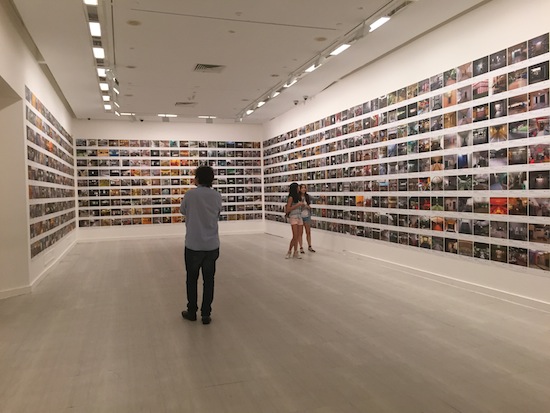

Time of Others – Contemporary Art from Four Museums across the Asia Pacific was the feature exhibition at the Singapore Art Museum (SAM) before it heads to partner gallery in the project, Queensland Art Gallery / Gallery of Modern Art (QAGOMA) in Brisbane.

Time of Others installation view at Singapore Art Museum, before the exhibition heads to Australia; Photo ArtsHub

Long time commercial gallery Chan Hampe Galleries, co-directed by Australian-born Benjamin Hampe, also choice to highlight an Australian artist at this time – Belinda Fox presented both at Art Stage Singapore and their exclusive Raffles Hotel space with her solo show Balancing the World.

Furthermore, a new publication launched at Art Stage Singapore – Catalyst – positioned Australia within the Asian roll call.

These relationships – despite a long presence of Australians working professionally across the arts sector in Singapore – still feel in their infancy.

Part of the reason may lie in Singapore’s preference to look north to more traditional art centres. But the weak relationships also Australia’s lack of engagement with Singapore as a serious art destination, many dealers and collectors opting, for example, to head to Hong Kong for its art fair.

There were however a coterie of Australian galleries that participated in Art Stage Singapore last week – Hugo Michell Gallery from Adelaide, Mitchell Fine Art of Brisbane, James Makin Gallery of Melbourne, and Sullivan + Strumpf and Martin Browne Contemporary from Sydney.

Building new markets

Founder and director of the private fair, Lorenzo Ruldolf said of this year’s edition: ‘In Southeast Asia (SEA) we have fairs – in Manila, Jakarta, Kuala Lumpur and Bangkok – but in entire Asia there are really only two truly international fairs that are able to position themselves as a brand and are building up new markets. One is clear – Hong Kong – Art Basel is the biggest brand in the world, and the other after only six years is Art Stage Singapore.’

‘SEA is growing without any doubt but you have to be clear, it is still a very emerging market. Contemporary art is still quite marginal and that means that there is a lot of information to give and a lot of education to do,’ Ruldolf continued.

In other words, a fair like Art Stage has the role to match-make these things to bring together the dialogue – that is one of the main targets the fair has. Despite all the success of the last years with a lot of international museums starting to collection SEA art, it is still not very well known. There is still a lot of promotion to do,’ he added.

‘We are today in a time when the market is absolutely dominant.’

Referring to last year’s record sale of Modigliani’s Reclining Nude painting, which was sold for $170 million by Christie’s New York to a Chinese buyer, Ruldolf concluded: ‘It shows us there are a lot of new buyers in the market; that art has became a status symbol and a lifestyle. Typically, that international art market is becoming more global, and Asia is becoming a more important in the market place.’

As a savvy economic hub, Singapore has recognised this opportunity. A How this ecosystem of market, education and cultural well being is played out continues to be revealed. What is sure is that Singapore should be noticed.