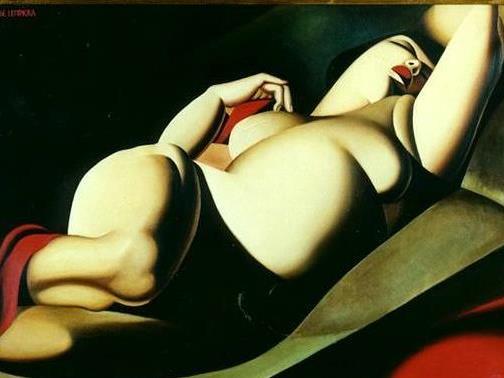

Image: Tamara de Lempicka via Fat People Art

A new writer-in-residence fellowship at the University of Sydney’s Charles Perkins Centre (CPC) is offering $100,000 for an established Australian author to “join the fight against obesity”. At nearly eight times the average income from writing in Australia, the privately-funded fellowship is bound to be it an attractive opportunity for writers, especially given the current arts funding climate.

The fellowship, which is billed as “the first of its kind in Australia”, certainly promises to be innovative (that most favoured of funding criteria). But before we all rush to apply, it’s worth pausing to think about the implications, not only in terms of the move away from government funding to private sponsorship, but also in terms of the specific – and specious – cultural and political agenda implicit in this fellowship.

This may seem like a perplexing claim – the CPC’s mission is to “ease the burden of obesity and related disease”, and health is regarded as an unquestionable good. But positioning “obesity” as something that must be combatted inevitably positions fat people as the enemy – a threat to the social fabric, economic prosperity, and security of the nation. This in turn justifies the use of dubious and dangerous tactics against those labelled “obese” – such as exclusion, shaming, biased medical treatment, discrimination, and for some, the experience of physical, sexual, and verbal violence.

Just a few days before the CPC fellowship was announced, social media had exploded with outrage over the news that at least two women on the London underground had been handed cards with anti-fat messages from “Overweight Haters Ltd.”

The messages printed on the cards – that fat is disgusting, fat people are gluttons who consume more than their share of resources in terms of food and public health services, and are sexual and romantic failures to boot – are identical to the messages promoted by public health campaigns against obesity. The reality is that “the ugly and awful card is simply an overt fat-hating action in a world full of other kinds of subtler, constant, and just as dangerous fat-hating.”

The difference between handing out anti-fat cards on the subway and sponsoring the creation of new work to help fight obesity is not so much a matter of kind, but of acceptability. While their methods may be cruder, Overweight Haters Ltd is a product of the same ideology as the CPC, and both reproduce the same discriminatory messages and the same discriminatory effects. Indeed, Overweight Haters Ltd can only exist because fat hatred is made acceptable, credible and respectable through the institutions of public health.

Anti-fat messages create stigma which has been linked to profoundly negative effects on health, including anxiety, depression, disordered eating, and – ironically – weight gain. This has lead organisations such as Obesity Australia (now part of CPC), to include “minimising weight bias” among their goals. It is difficult, however, to comprehend how calling on the medical establishment to formally classify a group of people as “diseased” will help to reduce stigma – but perhaps this lack of comprehension can be explained by the not-at-all-stigmatising notion that fat people are less intelligent and that is why they are fat.

This is not an uncommon tactic for those whose identities in some way circumvent the current cultural norm. After all, raced and sexed bodies have historically been pathologised for their apparent difference as a way to justify their experience of social abuse and discrimination. Those whose bodies are categorised as overweight are but the next in the long line of systemic and hierarchal oppression of physical bodies as sites of disease, fear, and difference.

This brings us to the question of which writers the CPC is hoping to attract. In a Facebook post about the CPC fellowship, author Amy Espeseth (whose debut novel Sufficient Grace won the 2009 won the 2009 Victorian Premier’s Literary Award for an unpublished manuscript) wrote:

“I’m genuinely perplexed. Should applicants supply measurements in their EOI? Will those who are shortlistees be weighed at interview? How much is a pound of flesh worth nowadays?”

The question of the writer’s body points to a number of problems with the call. The criteria state that the writer-in-residence must be an “Australian writer of international renown” who has had “a major creative work of excellence” published in the last five years.

But should we read between the lines and assume that fat writers need not apply? The plain of feature, perhaps, but certainly not the overweight.

Since fatness tends to be correlated with other forms of disadvantage, including socioeconomic status, race, gender and education, perhaps the CPC assumes that writers of sufficient excellence and renown would, of course, not be fat?

Of course this may be reading too much into things – as many would argue, the writer’s body is unimportant, what matters is their words. But again, this disembodied notion of writer raises ideological issues, enabling a mostly white, middle-class, cis-gendered, heterosexual, and privileged male perspective to figure as “universal” and occluding the work of minority writers, including women writers, queer writers, writers of colour, and writers with disabilities among others.

Fatness is only one of the many ways in which bodies which deviate from the norm are stigmatised and excluded. But because obesity tends to be more prevalent among already marginalised populations, it also works to stigmatise and marginalise them further. As fatness is seen as an individual failure – even when the influence of environmental factors is acknowledged – the responsibility for this stigma is transferred entirely to the individual, leaving systemic inequalities intact and beyond critique.

The CPC fellowship claims to be “a tremendous opportunity…to transform the world’s understanding of and attitudes towards the modern epidemics of chronic disease by interpreting them in a manner beyond the reach of scientists and clinicians.” But transformation cannot be achieved by insisting that fatness – and fat people – are inherently bad. Unless that changes, the centre’s quest “to inspire researchers within the Centre and across the University to think differently about their work and its impact outside of academia” can lead to nothing more than new, creative ways to perpetuate the same message and justification of hatred.

No doubt everyone associated with the fellowship and the Charles Perkins Centre believes that they are fighting the good fight. The problem is that it is construed as a fight in the first place. It’s not a fight that helps fat people. Rather, it is a fight that further entrenches structural and systemic inequality and discrimination. It is a fight that continues to justify stigma and hatred in the name of health. It is a fight that is will only support those who adhere to narrowly defined ideals of health and beauty, and separate them from those who do not.

The CPC writer-in-residence fellowship essentially constitutes funding for propaganda in the war on obesity. And make no mistake: the war on obesity is a war on fat people.