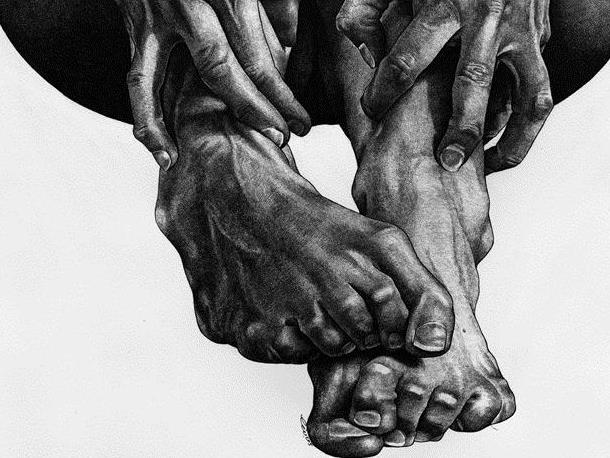

Detail of Overland cover art by Lily Mae Martin

Tough topics are embraced with gusto in this edition of Overland, which articulates the unsaid in its essays and fiction.

In her brief editorial Woodhead declares that the thread that binds this particular edition together is giving voice to ‘women’s unfiltered experiences of this world, and some other subjects on which there’s been far too much silence’.

Jane Rawson’s terrifying short story We Saw the Same Sky is perhaps the most daring work in this collection. A work of magical realism which interrogates the repression of asylum seekers, Rawson creates a dark fantasy that settles on the soul like the taloned monsters she conjures.

The finest works of horror are not those that create monsters but those that show us the monsters we are already becoming. Rawson’s leap of imagination delivers a gut punch to contemporary asylum seeker policy of tremendous power and originality.

Another brave and important piece of writing is Russell Marks’ essay on paedophilia and punishment, entitled More than Taboo.

Our newspapers and current affairs programs are filled with the horrors of child abuse, but Marks introduces a perspective that gets no airplay. He argues that the punitive horror with which we encounter paedophilia is driving the practice further underground.

Marks writes that the 21st century courtroom might be having much the same effect as the 20th century silence: preventing acknowledgement and healing. Specifically, he argues that preventing child abuse requires men and boys with sexual urges towards children to acknowledge and seek help before they offend. ‘That is unlikely in a climate of overwhelming and externalised judgement.’

Mandatory reporting, criminal proceedings and the demonization of offenders are now such standards of our society’s response to child abuse that Marks’ position requires courage. But it is this ability to rethink an approach that may have the seeds of a solution.

More personal pieces in this edition also display the courage to speak on difficult topics. Stephanie Convery’s confessional about literary jealousy exposes a dark shadow that polite society never acknowledges. Alison Croggan’s column on the ordinariness of female victimhood makes a short path from rape to academic exclusion; its deliberate non sequiturs revealing in their silences.

More analytically Brendan Keogh delivers a revealing dissection of the sexual politics of computer gaming. Keogh shows how the well-known incident of ‘Gamergate’, in which female game developers were subject to sexist online attacks, was an outcome of a patriarchal game culture, which privileges certain male perspectives and defines out gaming developed to meet women’s interests. The ‘nerds’ who were once the bullied of the schoolyard have reinvented themselves as kings of the gaming world but found their own victims in women who won’t play by their rules.

The edition also contains a beautiful story by Anne Hotta on male fear. Albert’s Medals, the story of a World War II veteran coming to terms with his dying son and his Asian daughter-in-law is a fine counterpoint to the prevailing Anzac culture.

Poems by the three winners of Judith Wright Poetry Prize give a touch of intimacy to this Overland, which is otherwise heavily political, even when personal.

Let’s hope it doesn’t just preach to the converted.

Overland issue 218 Autumn 2015

Edited by Jacinda Woodhead

Published by the O L Society Limited

overland.org.au

96pp, $19.95