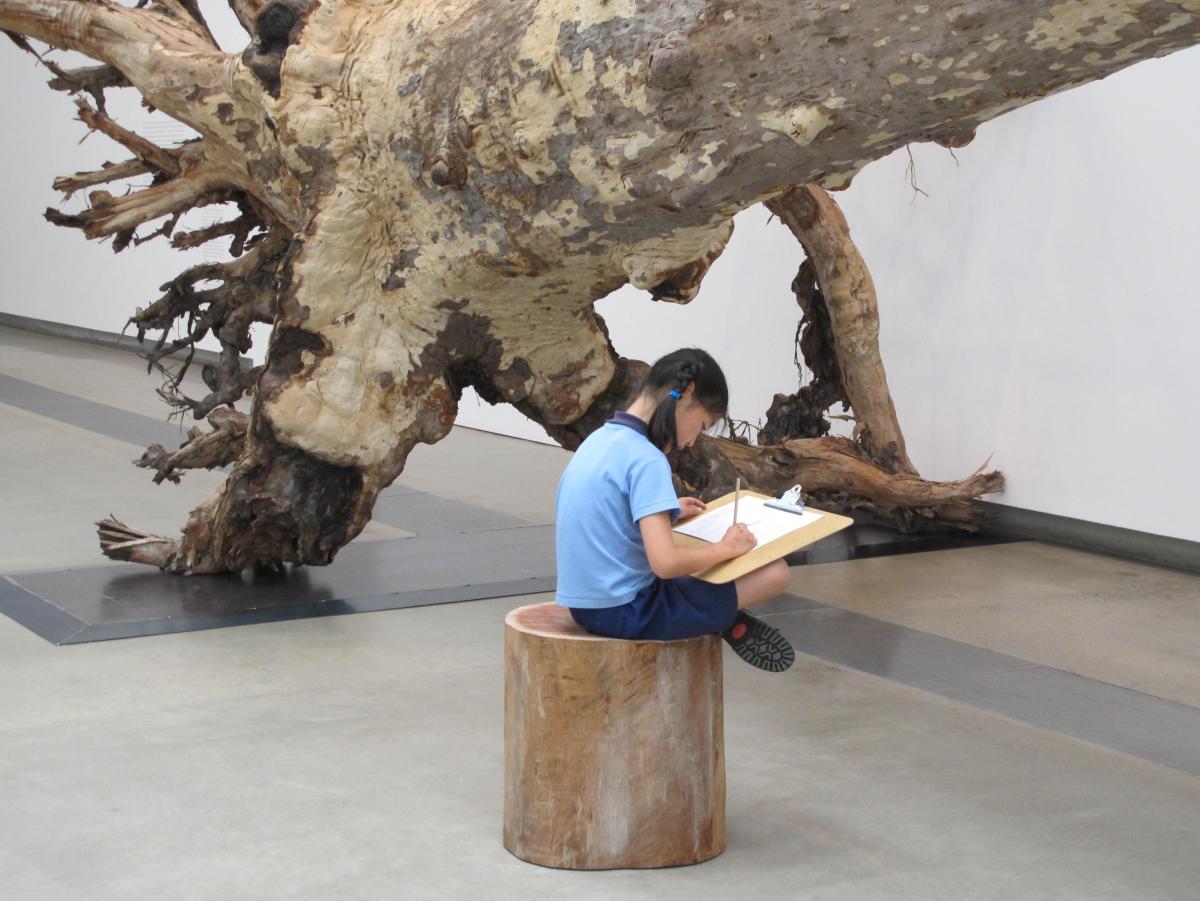

Drawing activity within Cai Guo Qiang’s exhibition at QAGOMA

In the past, children’s programming equated to the tailored guided tour – a school group was led around the hallowed halls of the gallery, intermittently plopped down in front of an artwork and given a bunch of ‘I Spy’ style questions.

Times have certainly changed.

In this two-part series, ArtsHub speaks with the Queensland Art Gallery/Gallery of Modern Art (QAGOMA) and Museum of Contemporary Art Australia (MCA), and looks at the shifting culture of Kids Programming. This week we ask, what it is that sees Australia regularly cited as leading the world in its initiatives of integrated, dedicated programming? In part two, we’ll look at what’s driving these programs and audiences – technology or hands-on activities?

One sure way to know this shift is working are numbers.

Donna McColm, Head of Public Programs, Children’s Art Centre and Membership at QAGOMA, said, ‘The December to January period used to be our dead time and now it is our busiest.’

With nearly 20% of attendance clocking in as family visits, these are figures to be noticed. Brisbane’s QAGOMA has garnered an international reputation for its Children’s Art Centre (CAC), developed when QAG expanded to its adjacent location in 2006.

Similarly, the MCA in Sydney radically redressed its Children’s Programming with the construction of its new wing in 2012 and development of its National Centre for Creative Learning (NCCL) occupying 40% of the new building. The results are paying off. Since opening, nearly 165,000 visitors have participated in Creative Learning programs, about 4% of the gallery’s attendance.

While these dedicated centres have defined the future of these institutions, this story starts well before these two new buildings.

McColm said, ‘We really started dedicated programming for this audience 15 years ago, so obviously that was just when we were at QAG. It was a very different model. In 1998 we moved from “lets walk around the gallery and talk about the works”, getting works out of the collection that we thought would appeal to children and curating thematic exhibitions for kids, to now [which is based on the idea] “how do you activate those spaces, and ideas and making”.’

Heather Robertson, Assistant Director Audiences and Creative Learning at the MCA said, ‘The NCCL provides unique spaces to extend exploration and engagement with contemporary art in ways that are not possible within the gallery environment. However, our starting point is always the art on display, so a crucial success in the design of the new building is the adjacency of the NCCL to the exhibition spaces to enable flow and interaction between exhibitions and programs and events.’

It is not just a change in programming; it is a change in museum culture.

McColm said, ‘We are finding anecdotally and through surveys that often a family will visit because a child has come in a school group to the CAC and they go home and say they want to go back. Adults are introduced to us through the child, which is the opposite of what it used to be, your parents dragging you along to the gallery.’

So the temptation then is more! How should galleries manage kids’ immersion with other viewing audiences? What is the right balance?

McColm said, ‘I think it is of more interest to critics than audiences or museum professionals. That kind of porousness is something we do deliberately. That idea about the space being completely democratic was confronting for some people, and for us that is just wonderful.’

The butt of such criticism, for example, was the gallery’s commission of Stockholm-based artist Carsten Höller to produce an installation of two spiral-shaped slides in GoMA’s foyer for 21st Century (2010). This exhibition also presented Olafur Eliasson’s participatory Lego work, The cubic structural evolution project (2004), which the National Gallery of Victoria showed in 2007 and the MCA in 2009 – testament to changing attitudes across all institutions.

Commissioning contemporary artist

Kids APT was the first real foray into commissioning contemporary artists for QAGOMA. In 1999, Cai Guo-Qiang, among other artists, created dedicated children’s artworks for the gallery; Cai returning this summer with another dedicated CAC project. Clearly, these institutions have placed children’s programming central to their inter-departmental and long range planning.

Similarly, the MCA has always worked closely with artists to develop and deliver their learning programs. Robertson said, ‘It is important to us that we employ artists as educators to design and facilitate our programs and to ensure that our visitors are directly encountering and meeting with artists when they visit the Museum.’

She added, ‘We also specifically commission artists to work on bespoke projects.’ A good example is the MCA’s Bella Program, established in 1993 but finding its true home with a dedicated space in the NCCL, and currently showing the sensory installation by Hiromi Tango.

Artist Hiromi Tango commissioned for MCAs Bella Room. Courtesy the artist.

Robertson explained the origins of this commissioning: ‘In 2006 the MCA invited internationally recognised American artist, composer and sound artist Bruce Odland, and sound engineer/researcher Michael Luck Schneider to come to Australia to develop and present a unique, multi-media, sensory art installation environment for students with disabilities. The resulting Good Vibrations exhibition travelled to school support students across NSW and Victoria.’

Not all galleries have the capacity or funding for dedicated children’s activity centres, yet with shifting trends are addressing such needs within exhibition design often using technology to extend the experience beyond a physical space – a topic we will cover in next weeks story across various galleries.

Another route taken is to receive dedicated children’s touring exhibitions – a new option fast on the rise.

McColm said, ‘We do an annual tour to regional and remote Queensland, very activity-based exhibitions, but touring these kinds of artworks is a big learning curve as they are basically conceptual works.’

QAGOMA has about 20 dedicated children’s works in their collection, from artists as diverse as Fiona Hall to Gordon Hookey. McColm added, ‘The thing that is really interesting is collecting contemporary works by artists for children, such as the Yayoi Kusama Obliteration Room, a Kids APT project that she gifted that to us last year.’ It is currently touring South America and Asia.

McColm believes this is a ‘new frontier’ for the gallery. She said, ‘It is sort of unprecedented touring this kind of work.’ The gallery also recently worked with Sydney Contemporary art fair to represent its Kids APT project by Indonesian artist Hanan.

So where does the future lie?

McColm said, ‘Contemporary art is still not the norm for an art museum visiting audience, so we have tried to make contemporary art accessible to all people – its not what you know before you come in through the door, it is about engaging with it on the spot, for example the drawing room for our Matisse exhibition where we transformed the gallery into a big drawing studio. We couldn’t have done that without all the knowledge we had built from CAC programming, and that is for everybody.’

McColm said, ‘One thing we always come back to is, we don’t see children and family audiences as separate … We really see that the children’s aesthetic experience is no different, so we are not ghettoizing these audience but rather opening them up.’

Such programs are not exclusive to QAGOMA and the MCA, with all state galleries and most regional galleries addressing young audiences in their programming.

Of note at the moment the National Gallery of Victoria (NGV) debuts its Children’s Festival next week to coincide with the Melbourne Now exhibition, and later in the year they will present Romance is Born (3 October – 28 June 2015) commissioned for the NGV International’s new dedicated children’s gallery and working with Sydney-based fashion designers Luke Sales and Anna Plunkett, blending art, music and design.

And the National Gallery of Australia is currently showing ToyShop in their dedicated Children’s Gallery (closes 6 April), more a traditional dip into the collection than a portal for hands-on activity, that is complimented by a dynamic mix of children’s programming in their Family Activity Room to coincide with their Gold of the Incas exhibition.

Check your local gallery for Kids programming over this holiday period.