There’s been no shortage of quality this year. You’ve probably read the award-winners and the eagerly anticipated, so knocking over the remaining books in this list will be quicker than a New Year’s pash.

This isn’t your guide to summer’s best reads. Though you’ll be immersed in faraway worlds you’re just as likely to be whisked away by literary chicanery and enthralled in the beauty of words. Some of these titles are demanding, confronting and perplexing, but this is why these books have been written across ‘best of’ lists around the globe.

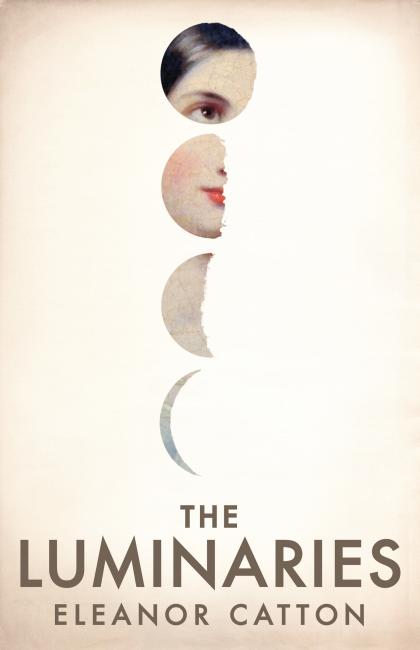

The Luminaries – Eleanor Canton

Speaking of demanding, 28-year-old Eleanor Canton’s Booker Prize-winning sophomore effort, The Luminaries is no paltry offering, weighing in at over 800 pages. Credited with illuminating a reconsideration of the long, long form and defying notions of screen-snapped attention spans, this might not fit your beach bag.

But it will transport you back to a 19th century New Zealand conjured from the cosmos. Though structured by astrology, with each of her characters stereotypically representing one of the star signs, there are no easy answers or offers of a personal reading at the end of a 1900 number.

Instead, what presents itself is a rumination on what it means to read and how we engage with characters – figments of another’s imagination that we’re somehow wrangled into caring about.

Marred in the Victorian vernacular of its setting, the book pays microscopic attention to the details of a world beset by civilisation and still struggling with its own savagery. Such a notion is messy, and likewise is Canton’s plotting, which resists straight trajectories and expectations, especially those of chapter length and typical characterisation.

No beach fodder, but an important work from the youngest ever winner of the Booker.

Barracuda – Christos Tsiolkas

And then there’s confronting. While the story of a champion swimmer setting out to win an Olympic medal might seem the plot of an inspirational telemovie, Tsolkias’ treatment of the subject is anything but wholesome.

The anticipated follow-up to The Slap continues Tsiolkias’ sharp-eyed dissection of contemporary Australia, and as Julieanne Lamond writes in the Sydney Review of Books, shows ‘the absurdity of the idea that Australia is a classless society’.

Through Daniel Kelly, a Scottish-Greek Australian of working-class background socially propelled via a swimming scholarship to a private school, Tsiolkas confronts our country’s complex relationship to sport and simultaneously uses the body, its limitations and exceptionalness, as the canvas to pound away at complex moral questions with broad, symbolic reach.

Burial Rites – Hannah Kent

The bidding war surrounding the manuscript for 27-year-old Kent’s Burial Rights is the stuff of authorial fantasies, reportedly fetching the young scribe a six-figure deal and putting her work alongside Graham Simsion’s The Rosie Project as the hottest titles in Australian publishing for 2013.

A historical novel set in 1830; Burial Rights relates the final year of Agnes Magnúsdóttir’s life, the last woman publicly executed in Iceland. As the name and premise suggests, it’s a bloody tale that draws from historical accounts of the murder of two men, including Natan Ketilsson, a well-known figure of the times.

Intricately rendered, Kent writes of the past and a foreign place with authenticity while staying near to the heart of her protagonist, a condemned woman bound by class and gender, that the reader is forced to make their own minds about.

The Narrow Road to the Deep North – Richard Flanagan

You can’t open a newspaper, browse a blog or scroll a Twitter feed without hearing about Richard Flanagan’s fifth work of fiction. Described by The Australian’s Stephen Romei as ‘the novel he was destined to write’, Flanagan’s account of the building of the Burma railway in 1943 by Japanese POWs may indeed be that. Inspired by his father’s survival of the bloody and torturous undertaking, Romy Ash exalts Flangan for ‘[juxtaposing] horror and love in a contrast that is so stark it can leave a reader breathless’.

According to all accounts, this is an exquisite, impressive book that should be atop every to-read list.

The Flamethrowers – Rachel Kushner

It’s not just Australian writers that have excelled this year. Across the Pacific Rachel Kushner’s second novel, The Flamethrowers has ascended bestseller lists on the rising cacophony of critics’ praise, while naysayers have been gagged like the woman gracing the book’s cover.

Containing an intoxicating mixture of narrative ingredients – a female bikie protagonist, European revolutionaries, and the New York art scene – these disparate scenes from the 1970s are seamlessly interwoven by Kushner’s incandescent prose.

If these seem the concerns of a male writer, you might have a mindset suited to the era of the novel’s setting, and be playing up to those aforementioned deriders. Indeed, Kushner’s latest work has raised the question of whether a woman can write the Great American novel of the 21st century.

Rather than indulge a stupid proposition, hear from the author herself in The Paris Review and prepare yourself with James Wood’s glowing review in The New Yorker.

The Love Affairs of Nathaniel P. – Adelle Waldman

From a strong female protagonist to a ‘self-regarding Man-Child’ by another New York writer (coincidentally), Adelle Waldman’s Nate Piven might be a boy that broke up with you via sonnet.

In The Love Affairs of Nathaniel P., Waldman examines the Brooklyn creative scene via the Man-Child, a 21st century anthropological curiosity that swings bed-to-bed through the urban jungle.

Though deft of touch and full of humour, Waldman’s investigation into the emotional retardation and delusion of her protagonist is an interesting entry into the novel of manners tradition. More so, it’ll leave pretentious, preening young men with literary aspirations more than a little uncomfortable.

The Tenth of December – George Saunders

Though you could’ve found one of these short stories published in various places between 1995 and 2009, it wasn’t until Random House published Saunders’ latest collection in January this year that they were available as a whole.

Though The Tenth of December traverses the darker aspects of humanity – rape, abduction, anger, cruel scientific experiments – Saunders manages to obfuscate the darkness with merrily penned prose and absurdity, though the current American economic climate blisters his characters, grounding the ‘dirty surrealism’ of the stories in contemporary concerns.

If this all sounds rather grim, check out Tegan Bennet Daylight’s review over at the Sydney Review of Books.

The Ocean at the end of the lane – Neil Gaiman

Beloved British author Neil Gaiman cemented his place as the heir of magic realism (though likens such labelling of fantasy as ‘a whore who wishes to be known as a lady of the evening’) with a book initially penned as a novella for wife Amanda Palmer.

Though Palmer apparently doesn’t like fantasy, The Ocean at the End of the Lane is as fantastical as any of Gaiman’s works, yet remains rooted in the everyday, so much as delving into his own past.

The main narrative begins when the nameless protagonist travels home for a funeral and reminisces on the time his father’s car was stolen and the thief committed suicide in the backseat. Though this tragedy allows a supernatural being access to the world in the book, this reportedly happened when Gaiman’s father’s car was stolen.

Perhaps it’s this conjuring of his own memory that allows Gaiman such adroit insight into childhood, and by extension the tension between innocence and experience that is the novel’s main concern.

Debuting at number one on The New York Times bestseller list, this surreal story is rich with symbolism and might be real (magically or not) enough to make you believe that pond is indeed an ocean.

Life After Life – Kate Atkinson

Earlier it was mentioned that the end of the year is an opportunity for reflection. Would you change anything in the past year? How about your life? What path would you take were you afforded a glimpse at your destiny?

That’s the question Kate Atkinson’s eighth novel asks via Ursula Todd’s innumerable deaths and rebirths. Though the narrative begins in 1910 it expires countless times before its culmination in the 1960s. Like a decapitated hydra each end is a new beginning and each death an evolution.

Though the narrative spreads in every direction, simultaneously discarding and embracing temporality and the rules of narrative, the ease with which Atkinson abuses the tenets of fiction is playful, pleasurable. Not only does she flaunt convention, but she proves the potency of the author’s power – you can kill characters and bring them back in different scenarios, different destines – just because you want, just because you’re the person writing it.

Though all writers posses this omnipotence, few actually have the grasp to exercise it.

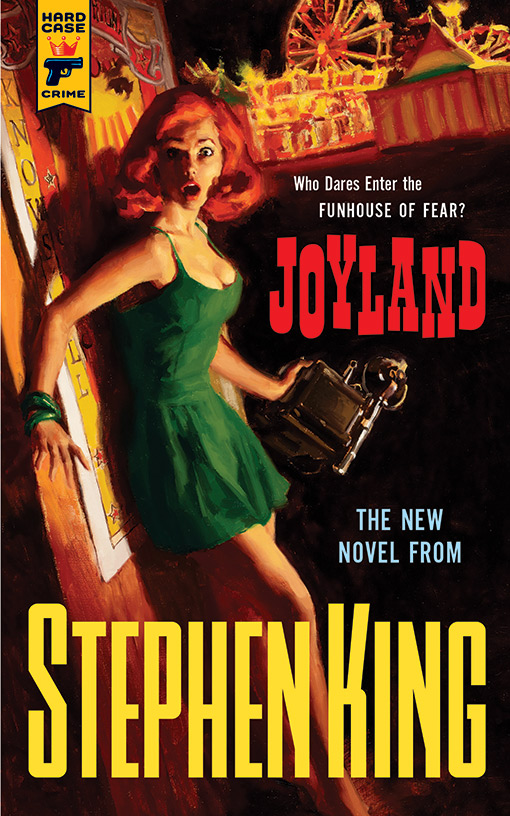

Joyland – Stephen King

If Stephen King is turning up on lists with best in the title, it’s bestsellers, and even then it’ll be Doctor Sleep, the sequel to The Shining. But Joyland deserves not to be forgotten. Not because of the insane, blood-soaked carnival setting, but because Stephen King is a badass and despite pioneering e-books, refused to let Joyland be sold in any form other than the physical.

With its beautiful pulp style cover by Robert McGinnis and its limited editions, Joyland keeps alive the smell of fresh ink and bound pages, even if its characters don’t last as long.