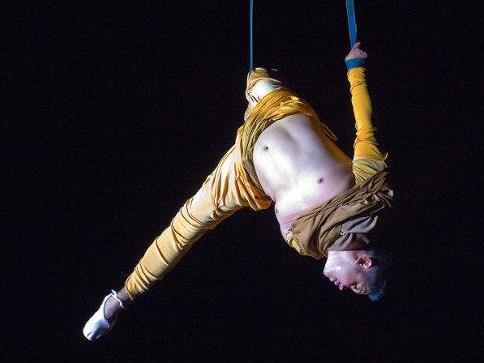

Image: From a production by Extraordinary Bodies, the UK’s only professional integrated circus company.

Contemporary circus is a celebration of the body; an art form that allows us to marvel at human physicality and skill. Whether aerialist or acrobat, juggler or contortionist, when we watch a circus performer, we are watching and celebrating a finely tuned and well trained body.

So if circus teaches us to marvel at the body, can it also teach us to embrace and celebrate bodies that don’t fit within traditional beauty norms – the differently shaped and the differently-abled?

Yes, says La Trobe University Professor Peta Tait, an academic scholar and playwright with an extensive background in theatre and performance.

‘The thing about circus is that it’s intended to amaze, so spectators are meant to admire what performers can do bodily and physically, and therefore there’s absolutely no reason why someone who’s differently abled could not become a circus performer in that way … the achievement of someone with a visible disability can equally be as amazing or admirable,’ she explains.

Difference has long been a part of circus tradition, though for many years it was relegated to the sideshow: the realm of bearded ladies, little people, and so-called ‘armless wonders’ such as Frances O’Connor, the Living Venus de Milo, who starred alongside many real-life sideshow performers in Todd Browning’s 1932 film, Freaks. But as contemporary circus became established, it embraced difference in a way that more traditional circuses had not.

‘What happened from the 1970s onward is that new circus, or contemporary circus – it’s called either – brought about a kind of association between circus and sideshow that was quite interchangeable. And you don’t have to go back very far, even in Circus Oz shows, before you find that clear link,’ Tait says.

Even at its most basic level, circus can subvert and challenge our notions about the body, such as by presenting performances by strong, muscular women whose bodies may not fit within the narrow confines by which beauty is traditionally defined – though at least one major international circus company sometimes seems at pains to ‘feminise’ its female performers through liberal application of makeup and gender-standard costuming.

But while professional circus companies are doing exciting work in challenging beauty myths, ability and body image – particularly in the UK, where a collaboration earlier this year between Cirque Bijou and community theatre company Diverse City led to the creation of a fully integrated professional company, Extraordinary Bodies – here in Australia it’s the community circus sector that is at the forefront of working with people with disability.

In Canberra, social circus organisation Warehouse Circus recently collaborated with Women with Disabilities ACT for an event as part of the Centenary of Canberra program, leading to the foundation of the Strong Women, Circus Sisters Troupe. The project, which aimed to break down stereotypes of ‘acceptable’ community activities for people with disabilities, while at the same time providing a fun fitness program for the participants was documented by photographer Aart Groothuis. The result was Strong Women, Circus Sisters – An Exhibition, consisting of 20 shots of the performers in training, as well as 15 portrait shots, and now showing at the Tuggeranong Arts Centre until 17 December.

Warehouse Circus training director Max Delves says the company has run several such programs this year, including partnerships with several Canberra special schools and a program aimed at adults with autism, primarily non-verbal men aged between 30 and 40.

‘Our rationale comes from the circus that we teach everyone, not just people with disabilities. We are a youth circus, and we have a focus on social circus, which basically aims to empower people, to encourage them to learn new things and find confidence in their own physicality,’ Delves says.

Based on her experiences training both abled and differently abled individuals, she sees circus arts as an excellent way of encouraging people to change their perceptions.

‘I think it takes tremendous courage to step into a new environment and try something new; I think everyone can relate to that. We teach workshops to able-bodied people all the time; for example we teach corporate workshops to people at a conference … and the most common response to being invited to participate and try something new is to say “no, I definitely can’t do that”. So absolutely yes, circus can encourage people to see people with a disability in a different light, particularly when they’re trying things that able-bodied people are often very reluctant to do themselves,’ she explains.

Given the growing popularity of social circus, hopefully it’s only a matter of time before differently-abled circus artists start to appear more regularly on our stages – a situation which will surely help to encourage society as a whole to be more inclusive of diversity.

‘Circus has increased in popularity a lot over the last 10 years, it has got very popular to take a circus course; it’s seeming more and more accessible, and I think there is definitely the opportunity for that popularity and accessibility to extend to groups of people, like people with all sorts of disabilities,’ says Delves.

‘Traditionally, circus has been a place for people who live on the fringes of society, people who don’t fit, and I think it would be amazing to re-embrace that, and I hope that time comes soon.’